A CRISIS OF UNDER ACCUMULATION

Capitalist profits have been falling, but not for the reasons that Marx said they would, says James Heartfield: it is not the objective laws of capital accumulation that are a barrier to growth today, but the subjective retreat of the capitalist class from industrial growth

It was Karl Marx who showed that banking crises are only symptomatic of more profound problems in the rest of the economy. Evidence of declining profit margins must surely vindicate Marx’s identification of the falling profit rate as the most important law of political economy. And surely, after years in the doghouse, the Marxists can be allowed to take some credit for anticipating the capitalist crisis.

It was Karl Marx who showed that banking crises are only symptomatic of more profound problems in the rest of the economy. Evidence of declining profit margins must surely vindicate Marx’s identification of the falling profit rate as the most important law of political economy. And surely, after years in the doghouse, the Marxists can be allowed to take some credit for anticipating the capitalist crisis.

Sad to say, closer analysis of the real underlying trends in the world economy make it clear that Marx’s celebrated theory of the tendential fall in the rate of profit has relatively little to tell us today. Marx’s theory is that rate of profit to capital invested falls, consequent on a diminished share of surplus value-generating labour (‘variable capital’) relative to a much greater share of investors’ money tied up in dead machinery, raw materials and plant (‘constant capital’), what Marx called the ‘rising organic composition of capital’ (see Marx, 1984: 211-231, Marx: 1969: 492- 516, Mattick, 1981: 43-77). But most of this conceptual framework is a poor fit to today’s circumstances. Marx’s theory assumes intensive growth of industry with a greater share of investment going to machinery, tending to displace living labour. Is that what has been happening in the preceding period, let’s say over the years from 1993-2005? Far from it.

Sad to say, closer analysis of the real underlying trends in the world economy make it clear that Marx’s celebrated theory of the tendential fall in the rate of profit has relatively little to tell us today. Marx’s theory is that rate of profit to capital invested falls, consequent on a diminished share of surplus value-generating labour (‘variable capital’) relative to a much greater share of investors’ money tied up in dead machinery, raw materials and plant (‘constant capital’), what Marx called the ‘rising organic composition of capital’ (see Marx, 1984: 211-231, Marx: 1969: 492- 516, Mattick, 1981: 43-77). But most of this conceptual framework is a poor fit to today’s circumstances. Marx’s theory assumes intensive growth of industry with a greater share of investment going to machinery, tending to displace living labour. Is that what has been happening in the preceding period, let’s say over the years from 1993-2005? Far from it.

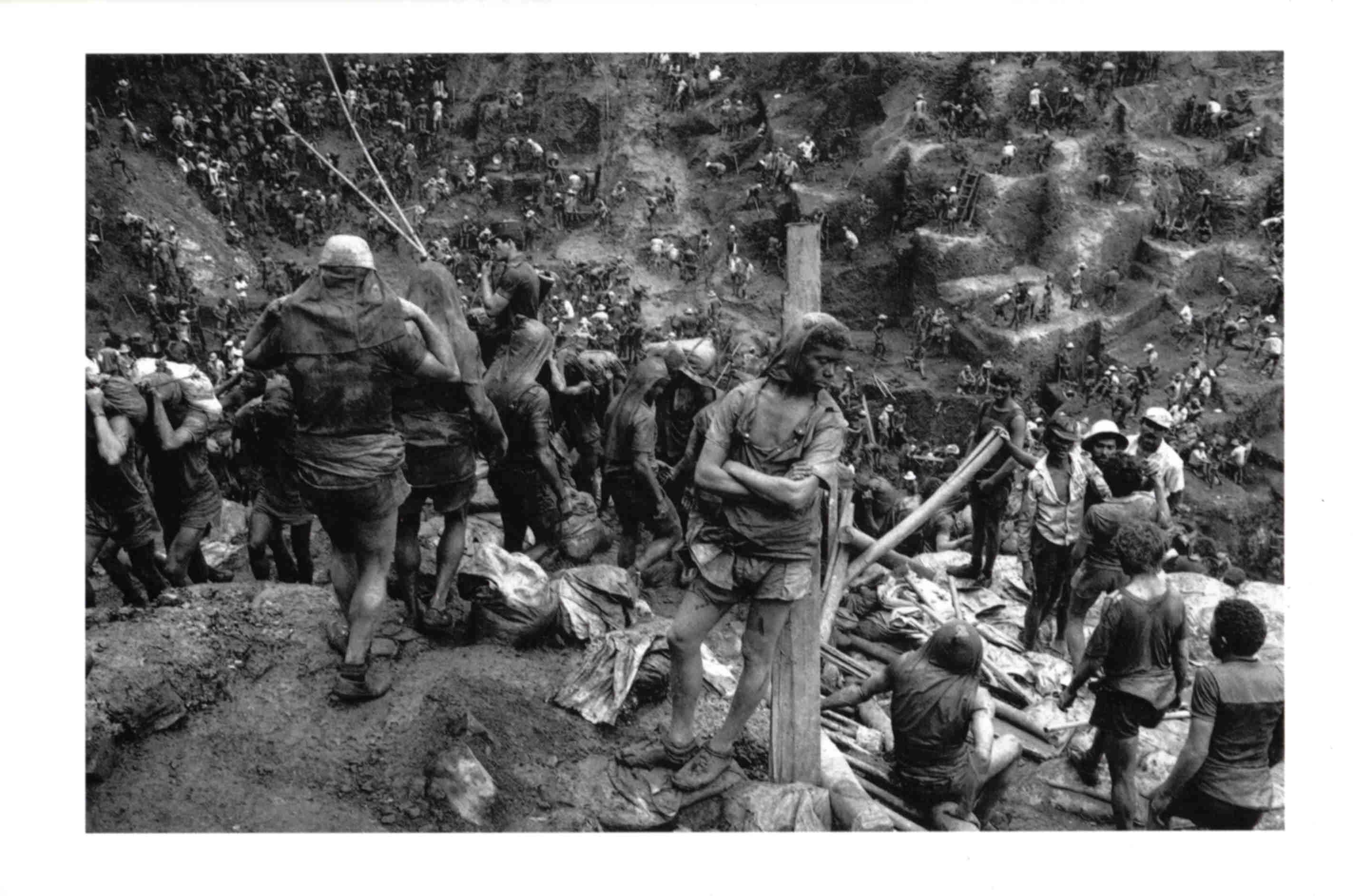

In fact, the post- Cold War era was marked by a phenomenal world-wide expansion of the labour force recruited into capitalist production, like these Brazilian miners photographed by Sabastiao Salgado (right). Between 1996 and 2006, the world labour force grew by 421 million jobs, from just under 3.6 billion to just over 4 billion (International Labour Organization, 2006).The largest growth in the workforce has come with the recruitment of millions of of wage labourers in those post-Stalinist and former nationalist regimes in Asia; but north America and even sleepy Europe have massively expanded their workforces by recruiting migrant labour, more women workers and incorporating Eastern Europe into capitalist production. Between 1988 and 2008 US payroll employment grew from 104 million to 138 million, much more than the growth in the natural population. The European Union increased its workforce from 60 to 65 per cent of those aged 15-64 between 1997 and 2008, as well as expanding eastwards to increase the total workforce from 174 million (EU 15) to 218 million (EU 27).

By contrast, investment in industrial capital has been very low indeed. In Britain ‘the economy has generated an additional 1.5 million jobs at a quicker rate than it has increased investment’ (DTI: 2001: 75) leading to the perverse ‘effect of lowering average measured productivity’ (DTI, 2003: 9). Similarly the 'investment surge' in Spain 'was not related to any large increase in labour efficiency' (Scobie, 1998: 7). In Holland, too, ‘the relatively good performance after 1987 was the result of a strong growth of labour input combined with a modest increase in GDP per hour ’ (Zanden, 1998: 159). According to the IMF ‘the ratio of employment growth to output growth is substantially above the historical norms in all four major euro-area economies’ (IMF, 2001). US business investment hovered around 13 per cent of output throughout the nineties and 00s.

Here’s compensation of US employees in private industries in millions of dollars (top line) and Gross private investment in millions of dollars (bottom line)

China’s growth, and the growth in Vietnam, Malaysia and Korea that preceded it, has put some vigour back into capitalism, filling Wal-Mart’s shelves (their industrial capitalism supporting our consumer capitalism, so to speak). For the most part the story of China’s growth is of a further extension of capital accumulation across the east, by the creation of new points of production, recruiting a new labour force, not of an intensification of capitalism with industrialization forcing labour out. Pointedly, it is not China where the problems have arisen, but in the less rapidly growing west.

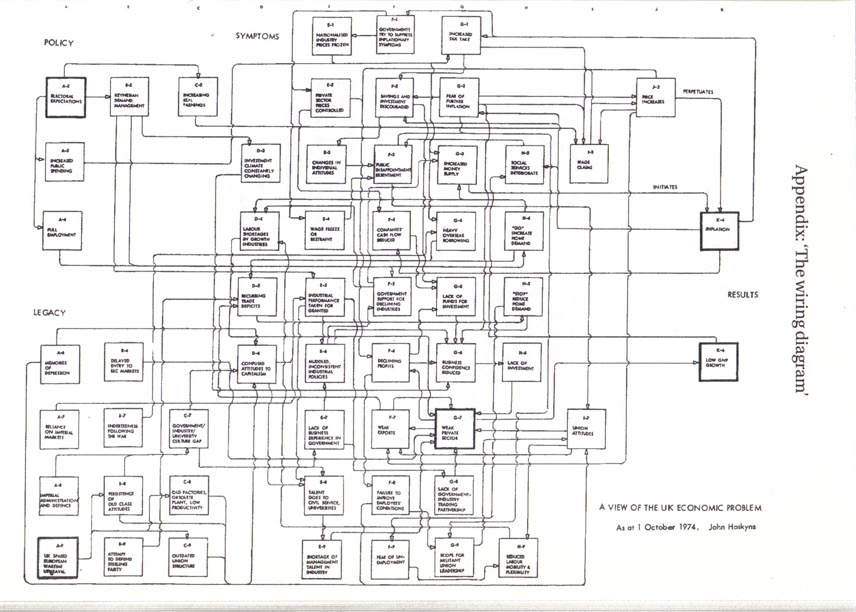

It is not easy to map Marx’s analytical categories directly onto empirical economic statistics (which are in any case distorted by many ideological devices). Still, in aggregate, the great growth in the labour force all points in the opposite direction to that indicated by Marx’s theory of crisis – it points to a stable or falling organic composition of capital not a rising one. Not an ‘overaccumulation of capital’, but underinvestment in new technologies. Not intensive growth forcing workers out as they are replaced by machines, but extensive growth sucking up more and more labour. Of course, as a consequence of the crisis, the layoffs are ratcheting up and unemployment is rising. But a declining share of capital invested in labour relative to machinery was decidedly not the cause of the economic crisis. Of course it is true that US non-financial profit margins went negative from the third quarter of 2005 (Smithers, 2009: 8 – though more recently, US profits have been rising again). But falling profit margins without a rising ‘organic composition’ of capital do not demonstrate Marx’s theory. (The temptation to see the economy as if it was a machine is not unique to Marxists, as we can see in John Hoskyns 'wiring diagram' of the U.K. economy, below.)

For some Marxists, workforce expansion can be dismissed as a growth in unproductive service workers – in the developed world at least, though decidedly not in Asia. In 2001, the U.S. service sector accounted for more than 80 per cent of the non-agricultural labor force, while the goods-producing sector employed less than 20 per cent (AFL-CIO, 2002: 1). On this reading, we can set aside the service sector, and discover a rising organic composition in capital-intensive manufacturing sector, leading to overaccumulation. But the identification of the manufacturing workforce in the national accounts with Marx’s concept of productive labour and service sector employment with ‘unproductive labour’ is too restrictive – a point which Anwar Shaikh makes (Shaikh and Tonak, 1994: 21), but then goes on to discount most of the service sector as unproductive in his analysis of the national accounts (Shaikh and Tonak, 1994: 29; Poynter, 2000: 198, makes a good case that much of what is called ‘services’ ought to be seen as productive labour). And if an economy can support some unproductive labour, it would be hard to understand the motives for such a great expansion of employment in the service sector if it created no new value for capital. What is more, if Marx’s theory accounted only for relations between labour and capital in one fifth of the economy, we would have to have a new theory to understand the rest.

One of Marx’s great qualities was his insistence on objectivity, refusing to substitute the wish for the thought. But amongst his lesser followers objectivity has shaded into objectivism, a mechanical reading of a mechanical society in which human subjectivity plays no role.

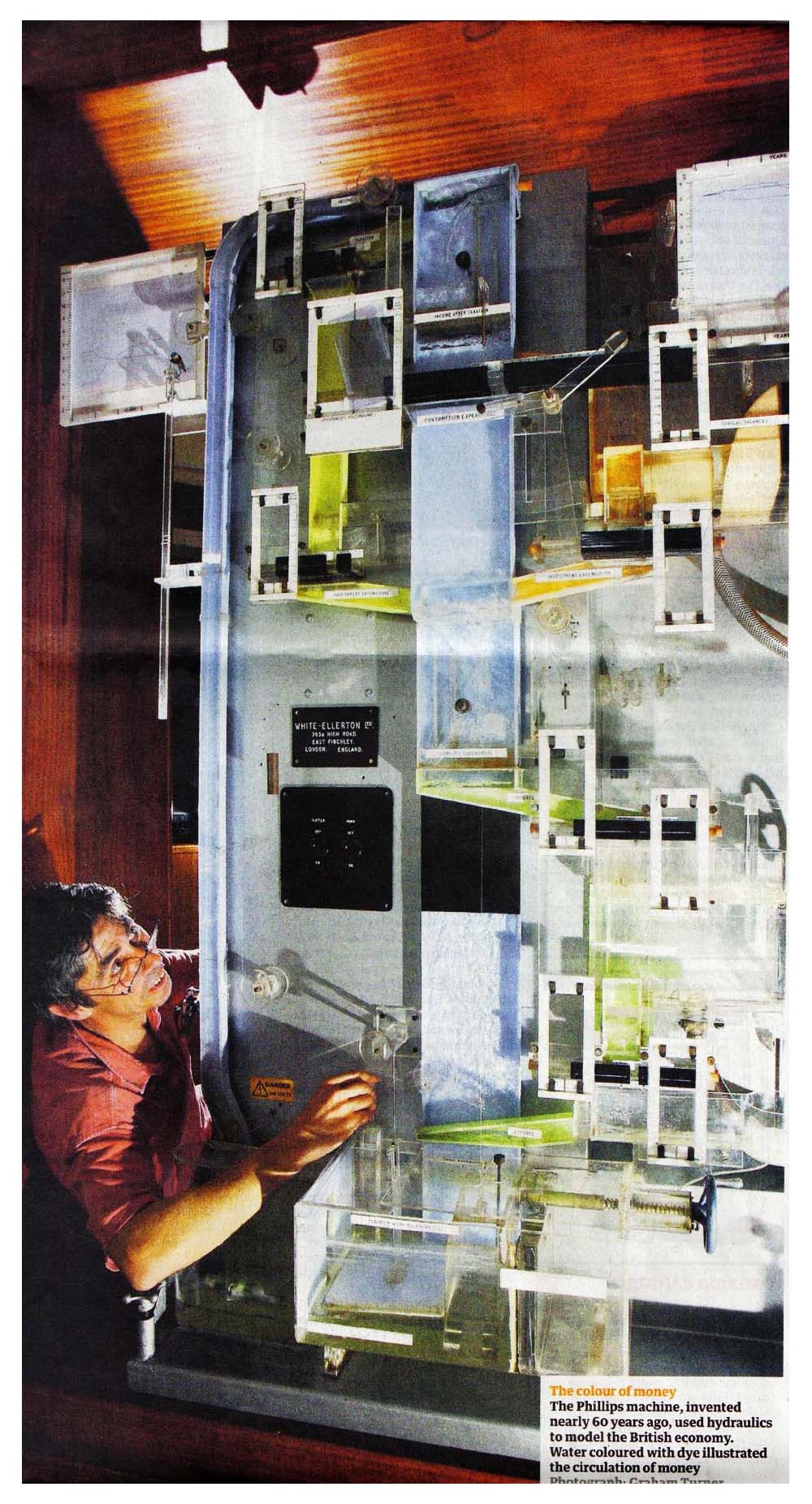

(Left: The Phillips Machine modelled the British Economy with coloured water for the Treasury Office)

Paul Mattick (who did more to resurrect Marx’s theory of crisis in the long years of the post-war boom than anyone) warned Science & Society readers against turning it into a dogma back in 1959: ‘For some of his disciples the “law of value” … seems to assure the breakdown of capitalism’, he chided, adding that for them ‘Marx’s critique of political economy became the ideology of the inevitability of socialism’. (Mattick, 1959: 33)

V.I. Lenin understood the pitfalls of objectivism

‘The objectivist speaks of the necessity of the given historical process; the materialist (Marxist) determines exactly the given economic form of society and the antagonistic relations arising from it. The objectivist, in proving the necessity of a given series of facts, always runs the risk to get into the position of an apologist of those facts’ (Lenin, 1894)

Such objectivism is all too seductive today because of the overwhelming importance – by its diminution – of the subjective factor in society (see Heartfield, 2002). Adapting Marx, Theodor Adorno said ‘Not only theory but also its absence becomes a material force when it seizes the masses’ (Adorno, 2000: 189) – in other words, the decline of the left itself becomes a material factor in history. First and foremost, it is the defeat of the left and of organised labour in the 1980s that explains the conditions for the survival of capitalism, and its expansion in the post Cold War era (the devaluation of ‘constant capital’ in the recessions of the early eighties and nineties helped, but was not decisive).

But just as important as the collapse of working class self-organisation, it is the the paralysis of elite subjectivity that explains the insipid and ultimately destructive character of capitalist expansion between 1991 and 2005. In 1938 Leon Trotsky proposed that ‘the present crisis in human culture is the crisis in proletarian leadership’ (Trotsky, 1977: 152) – a problem revisited with the outright collapse in such leadership and its corrosive impact on all classes. Marxists might be uncomfortable with such a conjunctural and subjective explanation of material conditions, but there it is.

To understand the decisive importance of the subjective factor, we have to look at both sides in turn, the subjectivity of the working class, and that of the capitalists.

In the 1980s, the resistance to capitalism put up by organised labour in the West, by the Stalinist regimes in the East, and radical nationalism in the developing world, effectively collapsed. Crushing organised labour was the condition of resumed growth. Employment gains, concluded the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, reflect ‘the effects of several years of wage moderation’ (2000: 11). Cheaper labour also takes away some of the motivation for labour-saving technologies, but as we shall see that is not the main reason. Elites in China and eastern Europe, having run their bureaucratic regimes into the ground, actively sought integration into the capitalist production process. The left’s collapse in the 1980s was what saved the capitalist system. It created new conditions for the expansion of capitalism, namely a supplicant labour force east and west –that expansion was not accompanied by the creation of new technologies, however but the squandering of lives in backbreaking, labour-intensive toil.

Though they were not defeated like organized labour, the capitalists as a class were exhausted by their victory. The only way they knew how to organize and re-organize production was provoking conflict, but in the 1970s that conflict had come close to wrecking their system. They fought hard to break up working class organizations in the 1980s, but in doing so they were wrecking some of the basic institutions that held society together. The capitalist class emerged from the struggle victorious but in a state of shock. Without a class enemy against which to organize they were prey to an extraordinary collapse in confidence.

Mainstream and radical analyses of the economy have blamed today’s problems on excessive risk-taking and the dash for growth, calling it ‘irrational exuberance’, ‘casino capitalism’ and ‘turbo-capitalism’. They could not be more wrong. What characterises today’s capitalist class is not excessive risk taking, but risk aversion. Far from pursuing growth at any cost, today’s capitalists have retreated from growth. If today’s capitalists look like giants, it is, as James Connolly said, because we are on our knees. Get up and take a look: they are insecure and timid midgets. The crisis of confidence in the capitalist class, more than any ‘objective conditions’ explains the insipid character of growth in the new millennium.

Those who take the opposite view will point to the exorbitant and speculative inflation of asset prices, to the great risks that the money markets took. But that is to see things the wrong way around. What happened in the new millennium is that investors confused a mathematical increase in asset values with real growth. The paper growth turned out to be a fantasy, not justified by a parallel increase in surplus value. Like Bialystock and Bloom in Mel Brooks’ Springtime for Hitler, the capitalists had massively over-issued shares in future productions. At a certain point those paper claims on new value could not be realised, and the crisis began.

In any number of ways, asset values were artificially inflated, usually by recycling profits to bid up the price of shares. In extreme cases like the energy broking firm Enron, growth bore no relation – or indeed a negative relation – to material output, being a construct of accountants who hid losses in subsidiary companies’ accounts, enlarging share values on paper. In point of fact what trading in energy Enron did take part in was to abuse monopoly control of energy supplies to extort money from retailers – winding down output not increasing it. The real growth, though, was magic money created out of money’s relationship to itself, wholly by-passing the process of material growth.

Enron’s outright fraud is exceptional for being illegal, but all too typical in the extreme over-valuation of assets, stoked by recycling surpluses into buying up shares. The banking collapse that was the proximate cause of the current economic crisis came about as banks’ assets were over-valued, with ‘toxic’ debts disguised in complex financial instruments.

The question that arises is why was the speculative bubble allowed to grow for so long without being called to account. Bubbles are a feature of capitalism, but for the last fifteen years we have seen speculative inflation of assets in emerging markets in Eastern Europe, new technology stocks, the fine art market and mortgage lending.

The question that arises is why was the speculative bubble allowed to grow for so long without being called to account. Bubbles are a feature of capitalism, but for the last fifteen years we have seen speculative inflation of assets in emerging markets in Eastern Europe, new technology stocks, the fine art market and mortgage lending.

The answer is that motive cause of the turn into speculative investment was a retreat from the world of industrial growth. Surpluses generated by industry were not ploughed back into new lines of production, but redirected instead into speculation. In Marx’s day he could still allow that the historic mission of the capitalist class was to revolutionise production, even if their goal was not increased output as such, but a greater share of the value produced. Industry was for them only a means to the end of increasing profits, and capitalists have often dreamed of cutting out the tawdry business of making things to make money out of money. But in the 1990s, that motive became predominant, as investors retreated from the tortuous challenge of transforming the realm of production, expecting gains without risk. Investors were not interested in new goods and services, but engaged instead in what the economists call rent-seeking behaviour. Their subjective recoil from industrial investments was reinforced by the higher returns offered by financial investments.

Though the multiplication of complex financial instruments traded in markets is often cited as evidence of excessive risk-taking, the truth is that most of these assets were developed to mitigate risk, and protect investors’ returns (see Ben-Ami, 2001). From the outset, trading in futures, options, interest rate swaps was all designed to hedge investments against risk. Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) developed computer models to remove the risk from trading. So too, the hedge funds that were responsible for witholding liquidity that tipped the banks into crisis in 2008 are funds created, as their name says, to hedge investors exposure by spreading it widely. The collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) that banks were trading in were designed to secure lending against excessive risk – a sign of caution, not excess.

At the same time the growth of future claims against wealth creation in bonds and shares came just as they were diverting investment away from that wealth creation. Around 2005, the material short-fall in wealth creation showed up when oil, foodstuffs and other commodity prices started their steep rise. There were just fewer resources being drilled, farmed and mined than money to pay for them. Banks accumulated toxic debts in their CDOs, and hedge funds acted to protect their investors in 2008 – all leading to the opposite of risk-free investment: collapse.

The businesses that grew in the new climate were those that were parasitic on insecurity. Between 1994 and 2004 insurance companies premiums grew by 50 per cent, to $3.3 trillion. In 2004, premiums in North American amounted to $1,217 billion, while the European Union generated $1,198 billion, and Japan produced $492 billion (Economy Watch, 2004). Civil liability claims and laws enforce a regime of protection against future risk.

Some of the most dynamic companies of the 1990s were management consultancies. Nervous managers of bloated businesses usually call in the consultants to make the difficult and unpopular decisions about which divisions to close down, and which to develop. Former consultant David Craig explained how the industry preys on corporate managerial doubts: ‘Like a cult, advisors encourage a cult of mystique and exploit the fears and power-jealousy of nervous and insecure executives'. (Craig and Brooks, 2006: 119)

McKinsey and Co. earned $5.33 billion in 2007 telling other businesses how to run their operations. It has been the firm that most MBA (Master of Business Administration) graduates want to work for since 1996. McKinsey’s advice is expensive. AT&T paid half a billion dollars. Was the advice worth it? ‘I just don’t know’ said one AT&T insider. Accenture, previously Arthur Andersen Consulting, earned $23.39 billion in 2008. PriceWaterhouseCoopers, moving into business services for the last ten years earned $28 billion. The key to understanding the growth of business consultancies is that they offer a resolution to that existential angst that besets all managers, fear of making their own decisions.

The astonishing growth in advertising ‘brand managers’ with Omnicom and WPP taking $13.359 billion and £7,476.9 million respectively in 2008, is also predatory on businesses fears of losing market share. These and other business services are growing because of the increasing trend for managers to contract out aspects of their decision-making to outsde companies. Right now consultancies are offering various snake-oil cures to ‘recession-proof’ businesses – and they will find no shortage of takers.

This was the meaning of all the ‘Lean Production’, or ‘small firm’ business theory (Smith, 1994), and the ‘post-material’ fantasy (Heartfield, 1998). The ideology of post-materialism gave voice to the retreat from industry. The great expansion of the financial sector meets this elite distaste for industry. Banking, insurance, stock-broking, futures trading and the mysterious trade in esoteric financial instruments are all businesses that are many removes from manufacturing. Entrepreneurs feel a lot more comfortable weaving money out of thin air than they do organizing the ugly business of production. The brokers’ analyst Alan Smithers explained how Britain’s earnings from financial intermediation had superseded those of industry in the nineties (Smithers: 2000). ‘Leave that to the Koreans’ our Trade and Industry advisor Charles Leadbeater said, we are all in the thin air business (he means intellectual property) these days (Leadbeater, 2000). Well, lo and behold! You cannot live on thin air.

Today’s managerial class are not used to confrontation, as this report by the internet company cScape points out: ‘CEOs have an average age of 50 in Europe meaning that their earliest experience of working life (1980, if they started age 22) was dominated by recession, whereas their career development would have taken place in an era of boom, from age 34 to 50.’(Perks and Sedley, 2008: 15) The managers that today’s managers replaced were the ones who did all the big lay-offs and rationalisations in the 1980s. Those 1980s hatchet-men, though, have all been replaced by people who are more used to evading problems than confronting them. Our current generation of managers only have experience of taking people on, and of hanging onto talent – that they call ‘human capital’ and ‘tacit knowledge’. It was under this generation of executives that personnel departments expanded, changing their name to ‘human resource managers’, so that office managers could avoid talking to their staff about discipline and other awkward issues.

One might think that it was a good thing for working people that company chiefs were a bit wet, given the impending economic disaster. But inadequacy has its own kind of tyranny. At the British Broadcasting Corporation management out-sourced much of its planning to consultancies (mostly McKinsey). BBC staff who did not have a project to work on were left on ‘downtime' or ‘gardening leave', as it was called. As many as one in eight were off work at one point around 2005. The reason for the waste was that management found it easier to avoid decisions than organise their staff. Over the last two years, cash shortages have been used to justify between 2-3000 redundancies. The difficulty for the BBC's employees is that the long periods when their managers could find no work for them would be hard to explain when they started sacking people on the basis of performance reviews. What was in fact the management's inability to organise its resources would show up on the individual's record as a failure to meet the BBC's programme making criteria or other operations.

One might think that it was a good thing for working people that company chiefs were a bit wet, given the impending economic disaster. But inadequacy has its own kind of tyranny. At the British Broadcasting Corporation management out-sourced much of its planning to consultancies (mostly McKinsey). BBC staff who did not have a project to work on were left on ‘downtime' or ‘gardening leave', as it was called. As many as one in eight were off work at one point around 2005. The reason for the waste was that management found it easier to avoid decisions than organise their staff. Over the last two years, cash shortages have been used to justify between 2-3000 redundancies. The difficulty for the BBC's employees is that the long periods when their managers could find no work for them would be hard to explain when they started sacking people on the basis of performance reviews. What was in fact the management's inability to organise its resources would show up on the individual's record as a failure to meet the BBC's programme making criteria or other operations.

In Ireland, where the recession has played havoc with public finances, government imposed a pay cut of eight per cent and above, and as has now emerged, the details were worked out by the public sector unions themselves. This trend towards a class collaboration approach to the recession is unfortunately the natural outcome of the twin crises in working class and employers’ leadership. In Germany, the government is subsidising Kuzarbeit (short-time work) while in the U.S. government the United Auto Workers played a key role in restructuring agreements with General Motors that will shed 68 000 employees, trading company debts to the pension fund for a stake in the business.

In looking at today’s challenges it is better to pay homage to Marx’s underlying approach than to any one or other of his worked up theoretical reconstructions of capitalist society. That is so, not least because it was he who made us understand that society is dynamic, constantly changing its own basis. When theoretical concepts stop being a guide and start becoming a barrier to investigation that is a problem. Marx’s reputation is strong enough to need no defensive calls of ‘we were right all along’ – which only serve to shore up the dogmatic claims of political sects.

The world economy is in deep trouble. That is not because too much has been invested in industrial machinery and plant, but because not enough has. The romantic anti-industrialism of the green movement might tempt Marxists to portray our problems as runaway growth, but that would be a mistake. It would be wrong to make a virtue out of austerity when working class people are being made to pay for the failures of capitalism.

James Heartfield, 7 November 2009

Adorno, Theodor (2000) Adorno Reader, Brian O’Connor ed, London: Wiley-Blackwell

AFL-CIO (2002) The Service Sector: Vital Statistics, Department of Professional Employees Research Department, Fact Sheet 2002, 5, Washington: AFL-CIO. http://www.dpeaflcio.org/programs/factsheets/archi...

http://www.bea.gov/National/nipaweb/TableView.asp?...

http://www.bea.gov/national/nipaweb/TableView.asp?...

Ben-Ami, Daniel (2001) Cowardly Capitalism: The Myth of the Global Financial Casino, London: Wiley

Craig, David and Richard Brooks, (2006) Plundering the Public Sector, London, Constable

Department of Trade and Industry (2001), UK Competitiveness Indicators, London: HMSO

Department of Trade and Industry UK Productivity and competitiveness indicators, DTI Paper no 9, 2003, London: HMSO

Economy Watch (2004) ‘The Insurance Industry’, http://www.economywatch.com/world-industries/insur...

European Commission, (2000) Report on the Implementation of the 1999 Broad Economic Policy Guidelines, European Economy Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs

Hayek, F (1973) Law, Legislation and Liberty, Vol 1, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul

Heartfield, James (1998) Need and Desire in the Postmaterial Economy, Sheffield, Sheffield Hallam University Press

Heartfield, James (2002) The ‘Death of the Subject’ Explained, Sheffield, Perpetuity Press

International Labour Organization (2007) Key Indicators of the Labour Market, Fifth Edition, Geneva, www.ilo.org/trends

International Monetary Fund (2001) 'Rules-based fiscal policy and job-rich growth in France, Germany, Italy and Spain’, IMF Country report No. 01/203, November

Leadbeater, Charles (2000) Living on Thin Air, London: Penguin

Lenin, V.I. (1894) ‘Materialism versus Objectivism’, http://www.marxists.org/archive/korsch/1946/non-do...

Marx, Karl (1984) Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol. III London: Lawrence and Wishart

Marx, Karl (1969) Theories of Surplus Value, London: Lawrence and Wishart

Mattick, Paul (1959) ‘Value Theory and Capital Accumulation’, Science and Society, Winter, Vol XXIII, No 1

Mattick, Paul (1981) Economic Crisis and Crisis Theory, London: Merlin Press

Martin Perks and Richard Sedley, (2008) Winners and Losers in a Troubled Economy, London, cScape

Poynter, Gavin (2000) Restructuring in the Service Industries, London: Mansell

Scobie, H.M. (1998) The Spanish Economy in the 1990s, London, Routledge

Smithers, Andrew (2009) US Profits: A High Risk of Disappointment, Report No. 334, 21st May, London: Smithers & Co. Ltd

Smithers, Andrew and Daniel Murray (2000) Britain: The World's Largest Hedge Fund?, Report No. 141, 14th January London: Smithers & Co. Ltd.

Zanden, Jan L. van (1998) An Economic History of the Netherlands 1914-1995, London, Routledge

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com