An Archeology of Camouflage

Roy R. Behrens:

False Colors—Art, Design and Modern Camouflage (2002)

Camoupedia—A Compendium of Research on Art, Architecture and Camouflage (2009)

Paris, 1914. One winter evening Pablo Picasso and Gertrude Stein are walking down the Boulevard de Raspail. Suddenly, they take notice of certain military vehicles featuring a camouflage pattern that looks rather odd but not at all unfamiliar: “We originated that,” Picasso says, “it’s Cubism!”

What does camouflage, considered by most to be the art of blending into the background, have to do with the wild patterns of Cubism? After all, what does it have to do with art in general? Roy R. Behrens, working as an artist, designer, and teacher of graphic design and design history at the University of Northern Iowa, has been researching the interaction between art and camouflage with steadfast dedication and great enthusiasm ever since the late 1960s. His earlier book in the field, False Colors: Art, Design and Modern Camouflage, is an outstanding achievement in that it connects seemingly disparate areas such as Zoology, Naval Camouflage and Architecture, which are usually treated in isolation from one another.

Let us see an example! American painter Abbot H. Thayer’s discovery of countershading in the protective coloration of animals had set the stage for the application of multi-chromatic camouflage to ships and military vehicles. His discovery therefore marks a new chapter in the history of military camouflage, which had previously applied monochromatic deception techniques only. The utilization of this new concept reached its peak during World War I when the belligerent powers used artists to design camouflage for their war machines. A new type of man appeared at the frontlines: the camoufleur. Often involved in or influenced by movements such as Cubism, Dadaism, Surrealism, or even Pointillism, the camoufleurs put the techniques of modern art to military use. It soon became evident that the goal of camouflage is not exclusively to make an object blend into the background (blending) or make it look like something else (mimicry) but to break up its contours into unrelated components. This latter technique is called disruptive camouflage or, when used for camouflaging ships, dazzle-painting. British artist and camouflage officer Norman Wilkinson soon realized that it was virtually impossible to hide a ship at the high seas, however, with patterns that disrupt the cohesion between the vessel’s structural units, it was possible to dazzle the eyes of German U-Boat captains and make it difficult for them to estimate the target’s size, speed, and course.

The guns and vehicles that Picasso and Stein spotted on the Boulevard de Raspail presumably sported similarly dazzling patterns and colors. Writers and poets were also flabbergasted by such a new application of modern art. For instance, Imagist poet Amy Lowell registered her experience of dazzle-painting in a poem entitled “Camouflaged Troop-Ship – Boston Harbor.” With art’s infiltrating the realm of war, disruptive camouflage also exerted a reciprocal impact on painting: In his 1919 work Dazzle-Ships in Drydocks at Liverpool English painter and camoufleur Edward Wadsworth (once involved with Wyndham Lewis and Ezra Pound’s Vorticist circle) captured his experience of a dazzle-painted ship becoming hardly recognizable within the vertical and horizontal beams and girders of the dock.

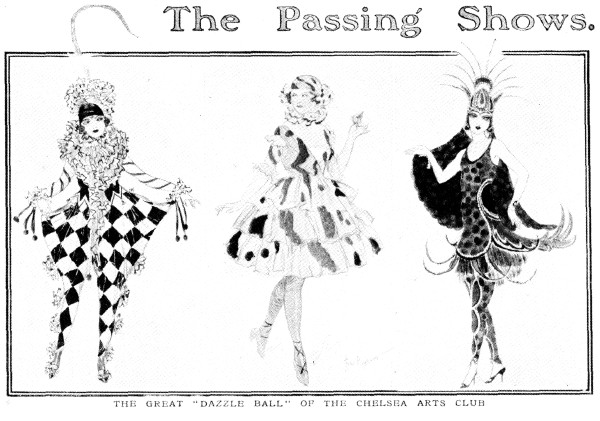

Throughout the Jazz Age dazzle-painting even influenced fashion and gave rise to a multitude of dresses and swimming suits featuring disruptive patterns that allowed their wearers to appear slimmer or, if so desired, more corpulent. What earlier had been meant to deceive submarines was now deployed on the social battlefields of salons and beaches.

It should be remembered that, behind such innovations in design and camouflage, also stand the discoveries of Gestalt psychologists like Max Wertheimer, Wolfgang Köhler and Kurt Koffka. Their work in the 1910s had paved the way for such seminal theoreticians of vision as Rudolf Arnheim and György Kepes in the ‘40s and ‘50s.

These interrelations, however, are only a few of the many intriguing connections that Behrens explicates in False Colors. Among the camoufleurs we can find names as famous as Salvador Dalí, Grant Wood, Arshile Gorky, Victor Papanek, and Bauhaus artist Oscar Schemmler who was involved in the camouflage of buildings. For a Hungarian reader like myself it has been especially enlightening to read about László Moholy-Nagy and György Kepes’s design to camouflage Chicago in 1942. Although their project was never realized, it attests to a fascinating effort in the history of urban camouflage.

Behrens’s archeological attention to detail and captivating style of writing guides the reader through the unchartered territories covering the no man’s land between academic disciplines. It is an ambitious and successful undertaking in that it excavates the history of camouflage through the oeuvre of the camoufleurs and, by doing so, it points to new horizons to be studied in art and military history. The left margins include additional information that runs parallel to the main text, yet the two remain closely interwoven, thus giving a layered, palimpsest-like quality to the book. Reading, in this sense, becomes an archeological experience.

Behrens’s new book, Camoupedia—A Compendium of Research on Art, Architecture and Camouflage is a continuation of his expedition. It offers an encyclopedic presentation of the vast body of his findings in camouflage arranged in alphabetically ordered entries. Its title derives from the combination of encyclopedia and camouflage; the meticulously compiled volume contains entries on artists related to military camouflage on more than 400 pages. Just as in False Colors the left margins add yet another layer to Behrens’s excavation work by bringing in additional information, mostly quotes, illustrations, and photographs which are woven into the fabric of the individual entries sometimes closely and other times more loosely. It is a very well illustrated book, featuring lots of previously inaccessible photographs and documents. The 40-page-long bibliography bespeaks of the accuracy and the far-reaching extent of Behrens’s research. The individual entries, as well as the information on the margins usually end with a list of related quotes, thus leading the reader directly to a first-hand source. This manner of presentation opens new doors and frontiers in a number of understudied areas in art and military history.

The introductory section delineates the major landmarks in the history of camouflage and explains the fundamental differences between blending, mimicry, and dazzle. After the encyclopedic section, along with the bibliography in the left margin, Behrens provides a camouflage timeline that gives clarity and a historical continuity to the events described in the alphabetical entries, which proves very helpful as a source of reference.

Although British and American camoufleurs represent a majority in the encyclopedia, Behrens is well aware that, in spite of the huge effort invested into tracking down the individual artists involved in camouflage, the work at hand turned into a bottomless well. “In the mid-1960s, when I began to research art and camouflage,” Behrens writes in his afterthoughts, “one of the questions I commonly asked was ‘Who was involved in camouflage?’ Now, more than forty years later, perhaps a more sensible question would be ‘Who was not involved in camouflage?” (393). As a gesture to invite young researchers to join in this project he inserts a section on “other camoufleurs” which includes a list of names and some data on camouflage-related artists he identified but hasn’t yet recovered any detail about their work. Given the interdisciplinary dimensions of Behrens’s work, researchers from diverse fields will surely find this list an incentive for further research. Still, one of the most outstanding merits of Behrens’s archeology of camouflage is that it highlights connections among these fields. And, like those ships in battledress at the high seas, Camoupedia has the potential to dazzle the eyes of librarians who attempt to categorize this book. On its the back cover the following categories are listed: Art / Architecture / Zoology / Military / Pop Culture.

I wholeheartedly recommend both books to all those who are interested in any of these fields and especially to those seeking connections between them!

The books can be ordered from Amazon.com at http://www.amazon.com/Camoupedia-Compendium-Resear...

or directly from the author's website at http://www.bobolinkbooks.com/Index/Home.html

László Munteán

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com