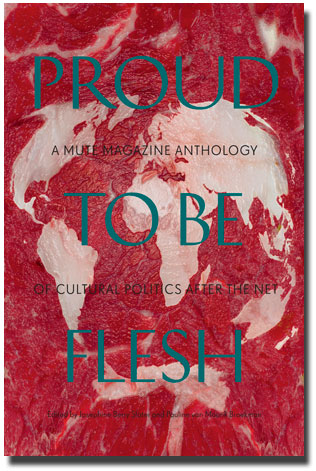

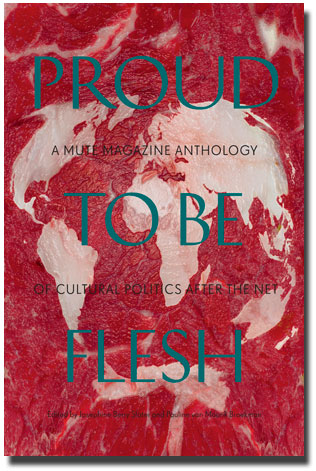

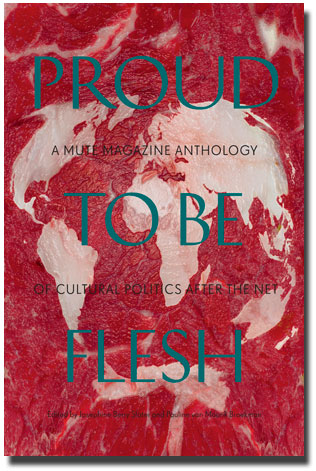

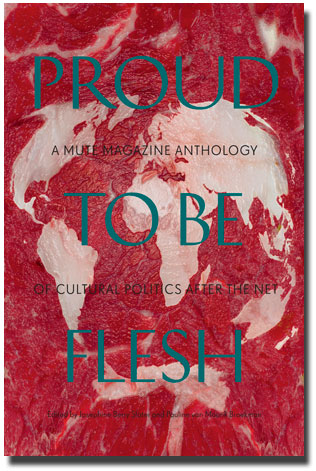

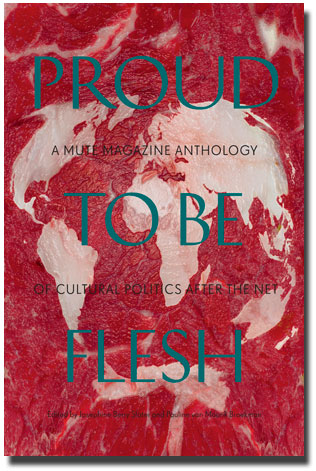

Proud to be Flesh

Buy print online:

UK - Amazon £24.99

US - Amazon $34.99

DE - Amazon EUR 33,31

In late 1994, back in the days of dial-up modems and Netscape Navigator 1.0, Mute magazine announced its timely arrival. Dedicated to an analysis of culture and politics 'after the net', Mute has consistently challenged the grandiose claims of the communications revolution, debunking its utopian rhetoric and offering more critical perspectives.

Fifteen years on, Mute Publishing and Autonomedia are delighted to announce the publication of Proud to be Flesh: A Mute Magazine Anthology of Cultural Politics after the Net. The anthology selects representative articles from the magazine's hugely diverse content to reprise some of its recurring themes. This expansive collection charts the perilous journey from Web 1.0 to 2.0, contesting the democratisation this transition implied and laying bare our incorporeal expectations; it exposes the ways in which the logic of technology intersects with that of art and music and, in turn and inevitably, with the logic of business; it heralds the rise of neoliberalism and condemns the human cost; it amplifies the murmurs of dissent and revels in the first signs of collapse. The result situates key – but often little understood – concepts associated with the digital (e.g. the knowledge commons, immaterial labour and open source) in their proper context, producing an impressive overview of contemporary, networked culture in its broadest sense.

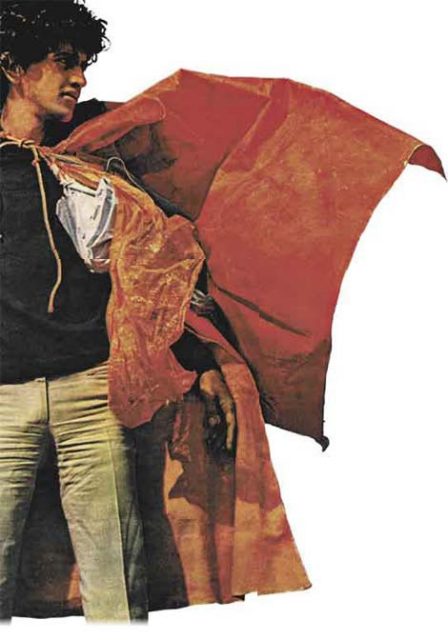

Proud to be Flesh features a bold mix of essays, interviews, satirical fiction, email polemics and reportage from an array of international contributors working in art, philosophy, technology, politics, cultural theory, radical geography and more. Accessible introductions, a chronological arrangement of chapters and three full-colour image sections grant special insight into the evolution of key themes over time.

In its refusal of specialisation, Proud to be Flesh is unique in its field. It offers a compelling view onto the messy but exciting moment that was the turn of the millennium as well as being an incomparable sourcebook for those seeking to push forward analysis of the global crisis that has since ensued.

ISBN Hardback: 978-1-906496-27-2

ISBN Softback: 978-1-906496-28-9

Date of Publication: 4/11/2009

624 page

Introduction – Proud To Be Flesh

Introduction to Proud to be Flesh

—

Foreword

Pauline van Mourik Broekman and Simon Worthington

The distillation of 15 years of Mute magazine content into one book has been a mammoth task, requiring what sometimes felt like a lifetime’s worth of re-reading, re-evaluating and searching for consensus, as we pulled apart our print and web archives and put them together again in a variety of constellations. When this process started, in 2002, we were working towards a very different anthology – provisionally titled White Cube, Blue Sky – which covered the relationship between net art and conceptual art (a subject receiving scant analysis back then and, we felt, pregnant with potential vis à vis the dearth of critically historicised readings of digital art and culture on offer). That particular compilation sadly fell victim to the resource-hogging juggernaut that is day-to-day magazine production, but its legacy is woven deep into this volume and remains most evident in the chapter entitled ‘From Net Art to Conceptual Art and Back’. This present incarnation of the anthology is indebted to Michael Corris who, acting as co-editor to Simon Ford, Josephine Berry Slater and Pauline on that earlier project, lent both historical insight and the all-important spur for us to re-orientate the book into a reflection of the magazine itself.

Proud to be Flesh is not a ‘Best of Mute’. Rather, it treats the entire back catalogue of Mute as its critical arena, exploring how the voices and ideas to which the magazine has played host crystallised into a set of distinct themes through which ‘culture and politics after the net’ (the magazine’s strapline since 2002) might be understood. Crudely put, this rounded on the utopian claims made for digital technologies in general and the internet in particular, subjecting them to a deepening critique, which ever more explicitly considered the socio-economic context created by capitalism. A typical example is the promise of democratic empowerment, via engagement with new media, which reverberated across a continuum from art to politics (discussed here in the chapters ‘Democracy and its Demons’ and ‘The Open Work’). Similarly, the emancipatory figures of the cyborg and, later, the immaterial labourer were said to augur a break in historical time with far-reaching consequences or gender, creativity and work – claims which are dealt with in ‘I, Cyborg’ and ‘Reality Check: Class and Immaterial Labour’. Concepts which emerged when internet discourse had ‘matured’, but which nonetheless accrued near sacred status as instances of a kind of public good – such as the information commons and, extending into the realm of social movements, horizontal organisation and openness – are tackled in the chapters ‘Of Commoners and Criminals’ and ‘Organising Horizontally’.

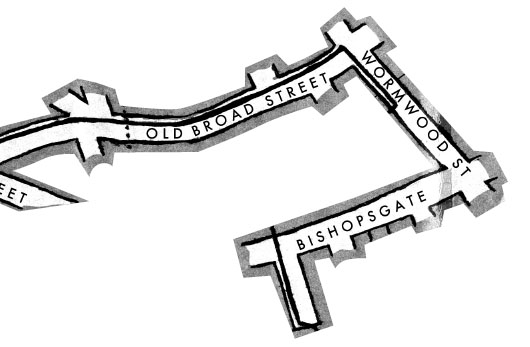

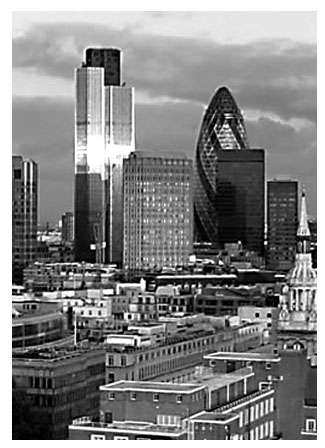

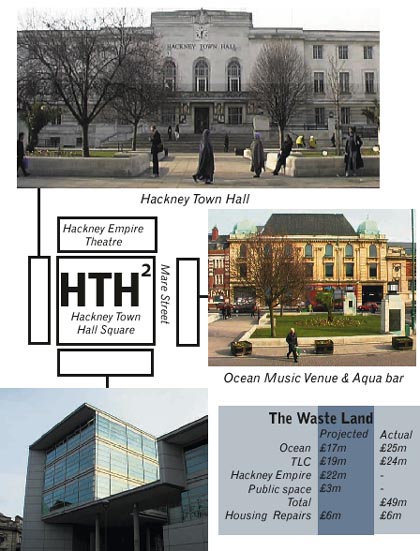

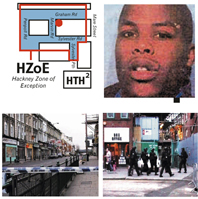

All of these themes will be more or less familiar from broader discourses on digital culture. Less immediately obvious are those topics that might be attributed to Mute’s location in London, the global heart of the financial services sector and the ‘creative economy’, a frontier space for the aggressive pioneering of neoliberal policies, from the nation state’s management of the arts to urban development and social cohesion. This necessitated an analysis of the civic assault suffered under the aegis of ‘regeneration’ and the antinomies of multiculturalism, and of artists’ insinuation into business agendas (detailed in ‘Under the Net: The City and the Camp’ and ‘Assuming the Position: Art and/Against Business’ respectively).

By arranging the content of each chapter chronologically, we hope to convey the sense of an evolving conversation and the structural effect certain texts and authors had on the magazine’s editorial (which explains some multiple appearances). And, while chapters tend to possess a germ, or concentration point, in particular periods, they also span our publication history, demonstrating the lasting import of their core questions and generating interesting parallels between ‘early’ and ‘late’ Mute, not all of which were conscious.

Looking back at some of the moments that defined production – at the back-end, as it were – the magazine’s history can quite easily be made to fit a certain clichéd image of a ’90s creative project. From the negotiations we conducted with the pre-print department at Pearson media group – to use the Financial Times’ purpose-built plant in Docklands on a test run – to the graft we put into cleaning an old, urine-soaked telephone exchange for the magazine’s launch party and the manner in which we subsidised our publishing activities with a mixture of commercial work and government aid, Mute looks every inch the do-it-yourself entrepreneurial venture valorised in creative economy doctrine.

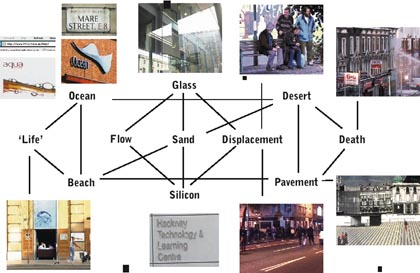

And, in many respects, it has been; aside from running as an actual business (rather than a volunteer collective, for example), the magazine’s foundational connection to the subjects of art and technology situated our work at the same nexus the British state sought to occupy as it amorously embraced the model of an ‘immaterial’ economy driven by creativity, knowledge and networks. Gradually moving eastwards from Shoreditch to Brick Lane and then Whitechapel (all of which saw local communities outpriced and displaced by a rapidly expanding ‘new’ economy hungry for office, retail and leisure space), even the Mute office resided at the juncture between the digital economy’s public façade and its underside – now dramatically visible as the global economy succumbs under the weight of its own contradictions.

Acknowledgements? It is hard to know where to begin… Mute has taken many forms, often in the name of professionalisation, but we have spectacularly failed to terminate the intimate connection between life and work. Loves have been found and lost, passions ignited, children born, and partners and parents have stepped into the breach. To attain even the smallest degree of veracity for this story, the definitive influence of the people involved must be foregrounded. From early editors, like Suhail Malik, James Flint and Jamie King (or even before them, Tina Spear, Daniel Jackson and Paul Miller), to what must be the longest-running editorial team of the magazine’s life (Hari Kunzru – with us pretty much since the beginning – plus Matthew Hyland, Demetra Kotouza, Benedict Seymour, Anthony Iles and Josephine Berry Slater, the latter three responsible for unstinting efforts in arguing the toss over the inclusions and exclusions of this book), to long-time designers Damian Jaques and Laura Oldenbourg, sales manager Lois Olmstead, and the countless individuals who either pitched to us or responded positively to pitches from us; it is these people’s ideas and collective modus operandi that have functioned as the engine of development.

Mute has run treatises on the plight of student interns in its pages, but we are not above accepting their generosity and Proud to be Flesh has enjoyed significant contributions from Hilary Crowe, Stefano di Cecco, Lars Dittmer, Paul Graham, Kate Guarente, Caroline Heron, Charlotte Levins, Hannah Marshall, Olga Panades, Joanne Roberts and Erin Welke in everything from archive mining to proofing.

To say this book has had a chequered history is an understatement: it has travelled from pillar to post, falling foul of mergers and acquisitions, new editorial directions and mysterious silences. Support was shown by Arts Council England and the British Academy, both of whom subsidised the anthology early on and who have proven among the most patient of funders. The last two years of gestation have seen Autonomedia show equal perserverance, and faith, in helping us keep the end in sight.

On the home straight, with Mute’s editorial contingent intensely pre-occupied (Pauline giving birth to baby Violet and Josie working flat out on the magazine), Rebecca Gordon-Nesbitt granted this book the final bout of intensive care, attention to detail and good judgement it needed, aided and abetted by Kyle McCallum. Long-time contributor, John Barker, also offered us the unanticipated luxury of an index. We’re eternally grateful for their last-minute agreements to participate. To have designers as perspicacious and text-obsessed as Sarah Newitt and Fraser Muggeridge to translate all this work into one coherent package has been the icing on the cake.

Finally, thanks to the ‘constructively’ critical but always serious family members who have followed – and supported – Mute’s winding path: Ernest, Kiddy, Ciska, Ritzo, Pam, Howard W., Raquel, Howard S. and Anthony. We know where you live.

—

Disgruntled Addicts – Mute Magazine and its History

Josephine Berry Slater

Mute magazine was born, somewhere between art school anomie and the thrill of the World Wide Web’s appearance, in 1994. Looking back at the magazine’s history on its 15th birthday, its most constant feature seems to be its wilful eclecticism and ceaseless criticality – something which, over the years, has got it into all kinds of trouble commercially, politically and with its varied readership. This concerted battle against the dominant logic of specialisation or static identity is perhaps the trace element of its founders’ art school backgrounds at the Slade and Central Saint Martins.

Simon Worthington and Pauline van Mourik Broekman knew practically nothing about publishing or journalism when they set out to make Mute. But, as artists working in the post-conceptual era in which the requirement to master a medium was lessening, they were primed and ready for practically anything. Inspired by the broader cultural experimentation at play (from DIY culture, to nomadic ‘briefcase art’, to the techno-aesthetics of magazines as varied as Mediamatic, Underground and Mondo 2000), they were looking for ways to break out of the conformist pseudo-activity of gallery and institutional art. Nevertheless, the desire to explore and analyse contemporary life in all its complexity – which could involve maintaining several conflicting ideas about something simultaneously, often resulting in a position of both criticism and support – could be seen as an overwhelmingly artistic approach that remains with Mute to this day. This refusal to unconditionally embrace a genre, discipline or political position is not only at odds with the niched requirements of the market, but also often with political and artistic tribes.

Mute’s stance of engaged criticality also seems to have characterised Pauline’s attitude to art in the early-’90s. As she tells it, she was a ‘disgruntled addict’ of art, sickened by the UK art world’s Thatcherite values in an era in the thrall of artists like Damien Hirst, but avidly following it nonetheless, scouring the scene for signs of activity at odds with the circus. Perhaps less preoccupied with the art world’s schizophrenic attempts to retain critical legitimacy in its phase of high commercialism, Simon was drawn to the greener pastures of the datasphere. Soon, both began to see the web as offering the possibility to do things otherwise, to elude the stultifying structures of official culture while at the same time acting on a global stage. This techno-social revolution in the individual’s ability to publish and access unfiltered information – to communicate globally without the mediating presence of elite gatekeepers – seemed to be having little impact on an art world obsessed with itself, its new found mass media appeal and Tracey Emin’s dirty laundry. Accordingly, Pauline and Simon identified a new editorial genre: ‘Digital Art Critique’.

From a small flat in West London, the by now paradigmatic ‘home office’ they shared, a marvellously hybrid bird of publishing paradise emerged. The first eight issues of Mute appeared somewhat quarterly, in broadsheet format and on salmon pink paper. Printed on the Financial Times’ own press, they spliced the austere conventions of 18th century newsprint typography with vector-based computer graphics, wacky fonts and articles on digital art and post-humanism. This retro-futurist gesture of covering the ‘information superhighway’ and its cultures on now historical newsprint was an unexpectedly popular bit of hype deflation. Mute’s ‘Proud to be Flesh’ slogan fired another salvo at the Cartesian/Gibsonian fantasy of ‘jacking into’ cyberspace and leaving the ‘meat’ behind. The spectres of pink paper and flesh were wielded against the rising crescendo of cybermania which would climax in the dotcom bubble of the late-’90s.

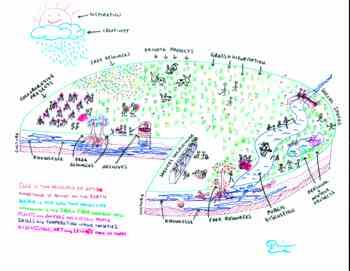

Beneath the playfulness, Mute was advancing trenchant critiques of what these dreams of disembodiment and immateriality belied. Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron’s text, ‘The Californian Ideology’, made an important contribution to this endeavour, exposing the neoliberalism and neo-Darwinism which lay behind Wired magazine-style celebrations of cyberspace and ‘bottom up’ phenomena. The image by CORP on Vol 1 #5’s cover proclaimed the words ‘Arbeit Macht Frei’ over a graphic of glass and steel office blocks and three flying computer keys – a reference to the expansion of work into daily life that digital technologies enable. Many years later, our ‘Underneath the Knowledge Commons’ issue, which carried a picture of a merry-go-round driven by flesh-and-blood work horses buried underneath it, would riff on a related theme – while elites experience the fruits of networked communication, the majority encounter an intensification of labour as managerial controls tighten and the ease of capital flight forces threatened workers to graft harder for less.

Focusing on the unsung, exploitative effects of new technologies, Mute has also consistently examined the unintended fallout from capitalism’s constant development of the forces of production – and by this I mean something more than the tendency for the rate of profit to fall. The internet, of course, is a tremendous case in point. Information piracy, peer-to-peer file sharing, ‘plunderphonics’ and plagiarism are all ways in which capitalism’s ability to create scarcity and control the commodity has been damaged by the net – that great, universal copying machine. Mute’s focus was increasingly the cultural practitioners and political activists – net artists and ‘hacktivists’ – who ‘misused’ the online environment to thwart attempts to own and control information and, hence, social knowledge and experience.

In 1997, some of Mute’s expanded editorial board – which by then included Hari Kunzru, Suhail Malik, James Flint, Jamie King and myself – took part in a presentation and workshop series at Documenta X called HybridWorkspace. This workspace, together with a net art installation elsewhere in the exhibition, were the first ever online and net art inclusions in a blue-chip, blockbuster art event. However, after the show was over, the organisers closed the Documenta site and saved the data onto discs which they then attempted to sell. But, participating net artist Vuk C´osic´ć had foreseen this and taken the precaution of saving the entire site to another address [www.ljudmila.org/~vuk/dx], making it publicly available as soon as the official site had closed. The ability of this new generation of web users to outwit the lumbering and proprietorial procedures of institutions and companies using digital tools created a window of opportunity and hope. The feeling that capitalism was a step behind its own state of the art technology created a rush of enthusiasm for alternative and anti-capitalist agendas.

To some degree, Mute attempted to manoeuvre itself within the commercial landscape of magazine publishing with comparable pragmatism and tactics. In 1997, we took the decision to come out as a quarterly glossy magazine, to situate ourselves on the news shelf (categorised, for want of any more suitable section, as ‘men’s lifestyle’), and to punt for some big advertising. From today’s perspective, it seems astonishing that we should have ever persuaded Silk Cut to pay for a double page, full colour ad in Vol 1 #8, our first glossy. It also seems astonishing that, at that tender age, we had faith in the prospect that Mute could garner enough popular appeal to become part of a mainstream media diet. Surrounded by a deluge of new lifestyle titles (Dazed & Confused, Adbusters, Wired UK), it felt like Mute might ride in their slipstream, buoyed by the growing enthusiasm for digital culture and our savvy, sassy approach. This strategy would also prevent us from becoming a service journal to the new media art scene, and open the door to taking a broader view on how technology affects all of life, not just certain discrete areas.

However, this desire to hack the commercial stratum of publishing did nothing to quell the disgruntlement and intellectual ambition of the magazine. Pauline’s editorial in Vol 1 #8 marked us out from the dotcom cheerleaders, by commenting on the ‘epitaphs’ already being laid at the ‘grave of the digital revolution’. The same issue also carried a meaty section on the maturing discourse of cyberfeminism, included a rave-inspired fashion shoot, my article on outsider art, bearing the title ‘How a Logic Logiced the System’, and Matthew Fuller’s piece on agent technology with sub-headings like ‘Backzoom: From Self-absorbed to Self-dissolved’. Hardly mainstream fare then.

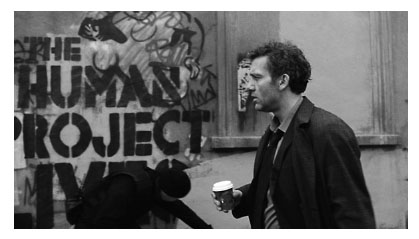

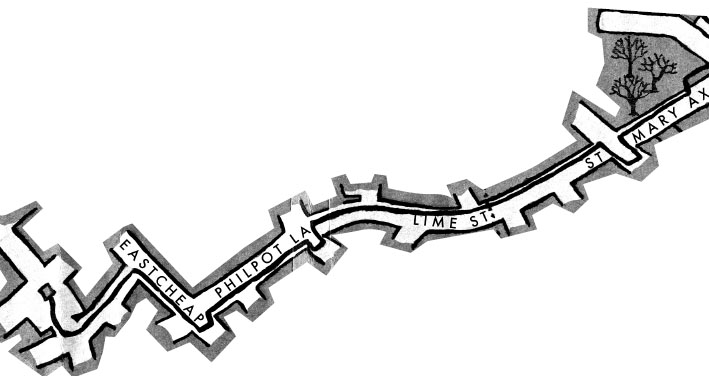

By the eve of the millennium, our predictions and dreams of two years earlier were proven to have been misplaced in both cases. The Silk Cut ads had tailed off sharply; but, on the other hand, the ‘digital revolution’ was converging with street activism to dramatic effect. While, for many, the November 1999 demonstration against the WTO in Seattle marks the consolidation of the ‘anti-globalisation’ movement, the Carnival Against Capitalism in the City of London the previous June marked its spectacular beginning, at least for Mute’s editors. At that time, our office was located in Shoreditch, a few minutes’ walk from the demo’s meeting point in Liverpool St. Station and I think it’s fair to say that the infamous ‘starburst’ of activists from multiple station exits, heading for the financial district beyond, is a force that propelled our editorial in a new direction, and one that increasingly came to dominate the focus of the magazine.

J18, N30, Genoa, 9/11; the arc of events is part of contemporary folklore. The ‘movement of movements’ shared many of the same organisational forms and techniques as the companies being restructured to suit the needs of capital and post-Fordist, managerial thinking. Flat networks, hollow organisations, alliances – capitalism and anti-capitalism were mirroring each other, as solid companies and once-unified political parties dematerialised into flexible, virtual and dynamic structures. ‘We are everywhere’ became a popular slogan for anti-capitalist groups and the title of a book dedicated to the rise of the movement edited by the Notes from Nowhere collective. Suddenly, thanks to computer networks, people could be effectively summoned from everywhere and nowhere to protest against equally diffuse elites who were dictating the terms of globalisation. Dumping the hierarchies, ideological clarity and arduous organisational means of traditional activism, large numbers of people were energised into taking part in politics on a global stage. Networks and mobility were the means, and direct action the result. But 9/11 changed all that. The declaration ‘we are everywhere’ was inverted into ‘you (terrorists) are everywhere’ and used to justify an open-ended War on Terror and on political activists.

As Jamie King asked, in his 2002 article ‘Terror is the Network – and the Network is You’ (Vol 1 #23), ‘what happens when the “network of terror” meets the “network society”?’ One answer is that this collision of networks intensifies states’ control and surveillance of their populations, counteracting many of the progressive applications of those same technologies in the name of security. The superficial parallels between Al-Qa’ida and anti-globalisation activists’ organisational means, not to mention their opposition to capitalism, played all too well into the hands of conservative and repressive state agendas. Jamie reports a headline from the New York Daily News, during the build up to scheduled protests against the World Economic Forum in the Big Apple, which declared: ‘New Yorkers will not be terrorised. We already know what that’s like. Chant your slogans. Carry your banners. Wear your gas masks. Just don’t test our patience. Because we no longer have any.’

Although the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq gradually dispelled this American mood of ‘righteous’ indignation, the mainstream’s post-9/11 sidelining of, and intolerance towards, summit activism seemed to deflate the confidence of the movement. The internal breakdown of its own fragile alliances, as many of its organising groups were accused of merely ‘summit hopping’, also contributed to the loss of momentum. Despite attempts to counter accusations of following the agendas of neoliberal elites by organising a series of alternative World and European Social Forums, once the focus had shifted away from the consensual target of free trade agreements and ‘damaging globalisation’ the alliances began to break down. Mute’s coverage of the 2004 World Social Forum in Mumbai and the European Social Forum in London was largely taken up with reports of infighting, exclusions and political censorship. Counter-counter summits began to proliferate and the Peoples’ Global Action network was besieged by accusations of Eurocentrism, racism and sexism. Were these anti-globos nothing more than First World ‘struggle tourists’ holidaying in other people’s misery?

At the same time as our writers were considering the social composition of the anti-globalisation movement, its structures and methodologies had also started to come under scrutiny. Activists’ constant foregrounding of the technical and organisational forms of collaboration seemed, after a certain point, to hide an absence of political debate and the emergence of crypto-hierarchies and geographical centres. Mute ran several pieces – by Jamie King, Anthony Davies and Eileen Condon – exposing the fallibility of this formalist tendency amongst alliance-political groups and reminding readers that we’d been here before in the 1960s and ’70s. Jamie referenced Jo Freeman’s 1970 text, ‘The Tyranny of Structurelessness’, which had pointed to the tendency for cliques to emerge within the same radical feminist groups that had overtly rejected the patriarchal structures of leadership and hierarchy, whilst covertly or unconsciously repeating their inequalities.

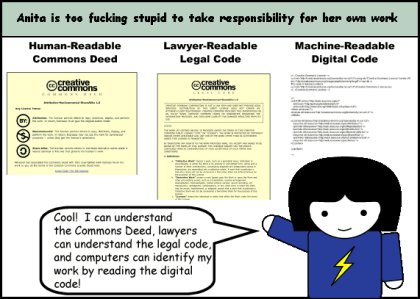

Since the sacred cows had started toppling, why stop there when so many others could do with a good prodding? The Creative Commons, locative media, social networking or Web 2.0 – the default piety that surrounded these apparently social initiatives beggared belief. What they all ostensibly had in common was literally the common, and a way of organising its production, or protection, using new technologies. What was suspicious was the level of commercial and governmental support they received; ‘movements’ that were notionally about devolving power away from states and capital were getting hooked back into them while claiming ideological purity. The Creative Commons licence, wrote Gregor Claude in his 2002 article ‘Goatherds in Pinstripes’, was not an anti-property initiative but a market-orientated attempt to distribute intellectual property rights amongst small scale producers; an anti-monopolist move aimed at developing a more dynamic and inventive marketplace. In the media art world and funders’ rush to embrace locative media, Armin Medosch and Saul Albert both detected a market-driven agenda, as hand-held devices and wireless networking became the cutting edge of the technological commodities market. Social networking sites or Web 2.0, argued Dmytri Kleiner, may have encouraged more people onto the net, but they drastically centralised the ‘means of sharing’. Web 2.0 effectively commercialised the developments of the free software movement and peer-to-peer file sharing, imposing a homogenised format on social communication and monetising its ‘long tail’.

Mute’s writers and editors were certainly alert to the infinitely cunning ways in which people’s communicative capacities and desires were subsumed into capitalist relations thanks, in part, to ICT. The politics of this subsumption had come to the fore with the publication of Hardt and Negri’s Empire in 2000 – a book which argued that ‘immaterial’ workers comprised a new revolutionary class as a result of capital’s dependence on their affective and intellectual labour. In this respect, immaterial producers could be said to ‘own’ the means of production, giving them a new autonomy. While critiquing the politics developing around immaterial production and the precarious conditions of its workers, Mute nevertheless shifted its publishing activities increasingly towards the immaterial realm. Having moved through a sequence of print formats and frequencies of publication we were, between 2002 and 2004, producing a thick, biannual coffee table edition. At this pinnacle of print luxuriousness, the high cost and labour involved in making the magazine were starting to take their toll. It was time to ‘jack’ our meat, and content, further into the web. We decided to go fully hybrid.

With Pauline and me going on uncannily parallel maternity leaves for the first half of 2005, this seemed as good a time as any to have a publishing holiday and completely overhaul the Metamute.org website. Simon and Raquel Perez de Eulate set to work designing and building a new site in Drupal – a free software, the bugginess of which has since earned it the reputation of a badly behaved household pet. Benedict Seymour and Anthony Iles had joined Mute as editors in 2004, and staffed the ghost ship Mute during this time, researching a cheap new form of printing called ‘print on demand’ (POD). This method – essentially a glorified laser print-out, prettified by the addition of full colour, perfect bound covers – allows one to print as few or as many copies as desired; you only have to pay for the number you need. This could not be more different from the newsprint process we had originally used, in which the minimum number of copies you could print was 10,000. With the show back on the road by mid 2005, our new model was to prioritise the website, publish weekly articles, solicit people to self-publish in the News and Analysis and Public Library sections, make our entire back catalogue freely available, and republish the best of each quarter’s crop of articles in POD form for an affordable £5.

In commercial terms, this was a risky approach since it removed any clear incentive for people to buy the print version by giving it all up for free on the web. As an Arts Council-funded magazine, however, part of our costs was covered and the wish to participate in international debates and free intellectual exchange outweighed any commercial advantage to creating a pay-per-view website. The readership results were dramatic, with Metamute.org averaging around 25,000 page views per day – although admittedly sales of the print version did nosedive for a while.

It is tempting to try and draw some analogy between our very noughties publishing model and the increased importance of the ‘virtual’ financial services sector to global capitalism, in the throes of its meltdown at the time of writing. The difference, of course, is that, with the shift from material commodities to the trade in intangibles orchestrated by the proliferation of new ‘financial instruments’, the city temporarily managed to make loads of money from producing nothing. Mute, on the other hand, belongs to the legions producing largely unremunerated content for the web. This condition some understand as ‘digital commoning’ – a way of collectively maintaining the resources which help the precarious intellectual worker to subsist within neoliberal globalisation as living conditions, wages and job security degenerate. This notion of free production, however, belongs to the phantasm of the ‘weightless economy’ in which money supposedly begets money and the cognitariat produce intellectual goods for nothing – a concept that came under fierce attack in Steve Wright’s article ‘Reality Check: Are We Living in an Immaterial World?’ (Vol 2 #1). Quoting Ursula Huws, he writes:

Huws draws our attention back not only to the massive infrastructure that underpins ‘the knowledge economy’, but also to ‘the fact that real people with real bodies have contributed real time to the development of these “weightless” commodities.’ As for determining the contribution of human labour within the production of immaterial products, Huws argues, that, while this might ‘be difficult to model’, that ‘does not render the task impossible’.

These ‘real people’, Wright concludes, are largely the ‘soil tilling’ majority of the Earth. The real commoner, it turns out, is capitalism whose non-reproduction of the natural resources and unpaid labour it loots is creating a tragedy of mounting proportions. As for those ‘digital commoners’, they are far from having transcended exchange value and returned to a pure reliance upon use values. Those commodities they continue to consume, and which sustain them in their immaterial production, are mostly produced by one hyper-exploited half of the Earth’s population. It goes without saying that Mute’s editors and writers belong to the lucky other half.

As the analyses of immaterial production, financialisation and ‘fictitious capital’ intensified after 2005 – due in no small part to the editorial input of Ben and contributing editor, Matthew Hyland – the focus on digital culture and art dilated somewhat. Perhaps, with the hindsight of a ‘once in a century’ financial crisis, it is hardly surprising that ‘fictitious capital’ developed such a hypnotic hold on our attention. In September 2007, we brought out possibly the best timed issue of Mute’s entire career. The ‘Living in a Bubble: Credit, Debt and Crisis’ issue, which we’d been preparing over the Summer, intersected ‘perfectly’ with the US sub-prime crash’s escalation into a full-blown credit crunch and the nationalisation of Northern Rock, the first in a long line of public bailouts it would later transpire.

But, despite the shift in focus, the parallels between the relational developments of art and virtual economic activity remain stark. Paul Helliwell contributed several lengthy articles on this subject, casting avant-garde art and, more latterly, ‘relational aesthetics’ as the vanguard of cultural commodification in its immaterial phase. Due to the commodity’s demise at the hands of digital abundance, he argues, the music industry in particular, and capitalism in general, are coming increasingly to resemble relational art. For several generations, artists have critiqued and abandoned the object; after the institutional critique of the 1960s–80s, droves of artists began to abandon the ‘white cube’ for the real world beyond, looking to ‘heal’ wounded social relations by operating on them directly. Thus was born ‘relational aesthetics’ as Nicholas Bourriaud termed it. Whether feeding the gallery visitor noodles or creating archives of collectively produced histories in the midst of regeneration zones, the artist became ever less the detached observer and producer of objects, and ever more the provider of social and cultural services.

Mute’s coverage of this cultural turn focused on how this once self-critical tendency became complicit with the forces of regeneration and social engineering. The London Particular’s image/text analysis, ‘Fear Death by Water’, and Anthony Davies’ article, ‘Take Me I’m Yours’, were key to this exploration. Both revealed a toxic mix of cuts in public spending and welfare, privatisation of the public sphere and the strategic deployment of culture to neutralise any resistance. This marriage of convenience between cultural producers and the neoliberal state results, they argue, in the consultative nature of community arts projects which do nothing to prevent already-decided-upon regeneration schemes, or the politically progressive programmes of institutions which nevertheless underpay their unskilled staff. This instrumentalised culture – which appears to be isomorphic with market deregulation and privatisation – is often the sad result of art’s critical dematerialisation. As with the ‘weightless economy’, art’s dematerialisation into a network of communication and relationality coincides with increased material hardship at the other end of the productive chain.

It seems that we’ve arrived back where we began, at the switch point between the liberating and repressive tendencies of dematerialisation. It is partly due to the overlapping concerns of these lines of enquiry that it took us over five years to assemble this book. Untangling the separate themes which now organise such a fat manual to the past 15 years of cultural politics took some doing. Art historian and Mute contributor, Michael Corris, gave us a great deal of help with this, moving our thinking on from the initial plan to make a book about the relationship between conceptualism and network-based art practice to a multi-themed anthology of some of our best articles. Reading over the book in its final form, I find it striking that a magazine which has continually contended with the question ‘but what’s it about?’ has, in fact, produced such a sustained and persistent analysis. The technologically driven dematerialisation of culture, economics, social activity and control must always contend with the material world of needs, production, embodiment and desires which sustain and are sustained by these processes. We are now, as ever, and for infinitely varied reasons, Proud to be Flesh!

Chapter 1: Introduction - Direct Democracy and its Demons: Web 1.0 to Web 2.0

Introduction to Chapter 1 of Proud to be Flesh - Direct Democracy and its Demons: Web 1.0 to Web 2.0

—

This chapter interrogates the web’s dual promise – to increase the direct democratic potential of many-to-many communication while, at the same time, perfecting the conditions for further expansion of capitalist social relations and the ‘free market’. Its timeframe spans the period between the pre-dotcom ’90s to the late Web 2.0-obsessed ’00s – a trajectory leading from the days of the internet’s initial and faltering marketisation to its mature, well-established form. As the net was popularised through Tim Berners-Lee’s invention of the World Wide Web and the first commercial browsers, the ‘commons’ of the internet – originally developed, owned and maintained by the state – was laid open to popular usage and vulnerable to a corporate land grab. Mute was keen to rupture the market-orientated hype of the ‘digerati’ prospectors, to expose their economic bottom line, and to insist upon the continuity of social relations across real and virtual space – in this sense, we understood ourselves as the European anti-Wired.

Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron’s article, ‘The Californian Ideology’, written in 1995, describes the stakes of this struggle between commercial and radical democratic forces, and importantly exposes the economic and political underside of the seemingly hip West Coast digerati gathered around Wired magazine. Politically conservative neoliberalism and techno-determinism were being repackaged as the daring embrace of the new network culture, as Newt Gingrich shaded into William Gibson. The workaholism of ex-hippies developing internet start-ups in garages and their ‘spare time’ was revealed as anything but the slacker culture it pretended to be. As with its classical antecedents, the virtual class, performing its intellectual labour in the electronic agora, relied upon an underclass of black and immigrant workers, excluded from the networks, to perform its reproductive labour for it.

Were the digerati concerned by these exclusions and did they think the technology could help society address such inequities? In his interview with legendary techno-booster and Wired editor Kevin Kelly, Jamie King reveals, with comic aplomb, the self-referential nature of the Californian Ideology. Kelly – who famously argued in Out of Control that, like life itself, technology is a vital force that should be subject neither to ethical judgements nor to developmental interventions – is at a loss to address the question of the ‘digital divide’ that is developing as a result of the networks he so passionately embraces. Throughout the interview, while claiming that ‘technology solves the ills of society’, he continually defends its unbridled commercial development on the grounds of its naturalness. Like most neoliberals, Kelly hides his rampant free market thinking behind a barrage of unsubstantiated clichés about the natural order of things.

Pit Shultz, co-founder of the nettime mailing list (one of the hubs of ‘European’ media critique), is equally concerned with the growth of virtual life forms, but from a very different political standpoint. In his interview with Mute’s Pauline van Mourik Broekman, he rejects claims that there has been a ‘digital revolution’ while still holding out hope for new media’s ability to create channels which ‘redirect the flow of power’. Without the freight of advertising, the channel produced by the mailing list itself is described as not only free but also ‘silent’, and, curiously, as a space that attempted to ‘avoid dialogues’. Early nettime was conceived as a ‘collaborative filtering’ project, not the space of rhetorical theatrics it so often became.

Anustup Basu, in his piece ‘Bombs and Bytes’, written in the aftermath of the second invasion of Iraq, laments the role of the media in driving the shift from democratic discourses, based on knowledge and persuasion, to the mass ‘psychomechanical’ programming of thought made possible by informatics. Providing an example of (corporate and state media’s) fascistic collaborative filtering, Basu cites the combination of the events of 9/11 with the name Saddam Hussein as a lethal instance of information’s malleability. In this ‘inhuman plane of massified thought’, it is possible to combine two ideas which have no organic or narrative connection.

The final piece in this chapter, by Dmytri Kleiner and Brian Wyrick, brings the discussion full circle. Web 2.0, they argue, the tools and platforms which finally made ‘mass participation’ in the web a reality, in practice amounts to little more than ‘Info-Enclosure 2.0’. Where the first round of the net’s enclosure was centred on its infrastructure (its backbones, ISPs, browsers and means of governance), the second has focused on the capture of community-created content and a homogenisation of the means of sharing.

What Barbrook and Cameron dubbed the Californian Ideology has, over time, revealed itself to be none other than the informatic dimension of post-Fordism itself. As with flexibilisation in the work place, what might at first have seemed to present small gains for the working class quickly establishes itself as a more individualised, finely grained and decentralised form of control. With Web 2.0 sucking the majority of web content production into a pre-formatted and narcissistic micro-casting, the big bucks are now determining not only the shape of social reality in its massified form, but also what Deleuze calls the ‘imperial-linguistic takeover of a whole social body of expressive potentialities’.

The Californian Ideology - An Insider's View (Re: Californian Ideology)

Re: Californian Ideology

I first read a draft of "The Californian Ideology" given to me by Andy Cameron during his visit to Los Angeles last summer for the SIGGRAPH 95 Convention. At that time, Andy was showing Anti-Rom at SIGGRAPH on my invitation as part of an exhibition of alternative new media called the lounge@siggraph which I organized for the conference. Andy was staying near my house at a beachside motel in Santa Monica and wore sandals for the entire period of his stay. We ate cheap Mexican food for lunch every day across the street from the Convention Center. We had lively discussions on a variety of topics. With the exception of a few technical problems during the show, he seemed to have a lovely visit with us here in California. If I am not very much mistaken, he left Southern California with a bit of a tan.

What, Precisely, Is California?

"American and England are two nations divided by a common language." so quote George Bernard Shaw some sixty years ago. But there's more to it than mere linguistics. Especially when you are talking about California.

It is typical of Americans to be myopically ignorant of their own history-not to mention everyone else's-which is how the Republican Party is able to repeatedly succeed at the polls. But a glimpse into our history, and particularly the history of California, is useful in understanding the basis for the Californian Ideology.

California is and has always been characterized by pioneers and golddiggers. From the gold rush, to the movie industry, to the computer revolution, the Californian Ideology has always been one of spirited individualism and entrepreneurialism. A less utopian way to look at it is that California is a breeding ground for greed and self-interest. Both interpretations are correct. By way of example, take a look at this list of just a few of the things California has brought the world:

LevisMoviesCharles MansonThe Grateful DeadRonald Reagan and Richard NixonSilicon GraphicsMicrosoft and AppleIndustrial Light & MagicLos Angeles and San FranciscoScientologyDisneyland

A Member of the Virtual Class

Bearing all that in mind, I'd like to analyze some of Cameron and Barbrook's points from the perspective of someone who must live-and survive-the Californian Ideology on a daily basis. By way of qualifying that statement, let me confess at once and without shame that I am a member of the "virtual class" described in the article. The description of this individual-the independent contractor, free to come and go as they wish, well-paid, but at the same time, suffering from acute workaholism-fits me to a tee. All except the well-paid part. And that is a myth. It is true that many of us are well paid by the hour. However, it is also true that many of us spend between fifty and seventy-five percent of our time trying to secure that hour of work. Furthermore, prospective clients often expect us to do work on spec or for very low rates, often with no assurance that work will not be used without our participation. Those of us to are pushing the envelope the hardest, and particularly, those who are trying to make product with social and cultural merits, must fight every step of the way. The people who are at the forefront of the digital revolution, the true vanguards, are blazing their trail at tremendous personal risk.

The condition of the virtual class cannot be blamed on the individuals within it, but must be looked at in a larger context. In America, artists receive very little support from the government or, for that matter, the society at-large. Since the 1930's and the New Deal, when WPA funding was created to support a variety of arts and cultural projects, America has systematically eroded away its art and cultural support, much as a desperate animal gnaws its own foot off to release itself from a trap. In our anti-intellectual culture, artists are considered subversive and unnecessary. In America, anything that does not generate revenue is viewed as gratuitous.

And herein lies the key to understanding the Californian ideology. The most important thing in America is making money. Period. If we begin our discussion starting from that axiom, we can start to make a little more sense of what the Californian Ideology is all about.

"Bigger is Better"

In many arenas, America prides itself on matters of size. "Bigger is better" is the general belief. But one of the primary reasons for the average American's sense of political impotency is that America is quite simply too big to manage. The European Community will ultimately be a better model for managing governments than the United States of America. If you look at any large country with a large physical area and a large population, you will recognize that it is almost impossible to run a large country with any measure of freedom to its members. If you are autocratic and highly centralized, as was the Soviet Union or the People's Republic of China, you can have some measure of control. However, once you start letting people have any say in what's going on, things start to degenerate, as we are now seeing with former Soviet republics.

To compensate for this flaw in large-scale decentralized management, we have developed, in the form of corporations and companies, our own form of a tribal culture. Big companies like Disney, IBM, McDonald's or Coca-Cola, are small nations unto themselves with their own culture, ethics, even their own language. These tribes cluster themselves into "industries"-software, entertainment, automobile, and so on. It is within these corporate tribes that most Americans find the unity and security one might expect to be provided by government in a place where the "common good" is seen as a priority.

Capitalist Cyberhippies

Why is Silicon valley overrun with capitalist hippies? It is easy to label these individuals are revolutionaries who "sold out" to the capitalist ethic. But when you live within that ethic, you can also look at it another way. We learned in the 1960's, after our President, his brother, and our two most influential civil rights leaders were murdered, that politics was a dangerous path to take in building a revolution. The Nixon regime further drove home the point that politics was no place for a respectable individual to devote their time and energy. Furthermore, it doesn't take a genius to see that in reality, there is no politics in America, only economics. So to say that Americans are apolitical is absolutely correct. And that is because our country is about economics, not politics. In Europe, there are countries. In America, there are corporations. It is the corporations who take care of the people, not the government. Those things which are typically government supported in social democracies, like medical insurance, education, and even the arts, are provided by corporations. We have created a modern-day feudal society. And the only way to secure any real power in America is to either make-or control-large sums of money.

In the 1960's, the generation that seemed destined to revolutionize America was utterly derailed by the events described above from a political path to change. They did, in fact, change America, but not in the ways we thought they would. Those who would have excelled in politics turned instead to industry. In another time and place, it might have been Bill Gates in the White House rather than Bill Clinton. But their generation learned the hard way that politics is as treacherous in America as it is pointless. The mere comparison of the two Bills should attest to that.

Siliwood & the Military Entertainment Complex

From Silicon Valley, you can follow the California fault to the other nexus of activity in California-Hollywood. Hollywood is the home of the entertainment industry, Silicon Valley of the computer industry. And in the past three years, these two powerful forces have "gotten in bed together" (as we say in showbiz) and given birth to a new phenomenon aptly known as "Siliwood."

But beneath the self-congratulatory glitter of this marriage, both regions are tied together by a much stronger bond, a bond much less glamorous, but no less profitable. That bond is the military. As "The Californian Ideology" very astutely points out, virtually every aspect of the computer industry has its roots in government-funded military technology, and California has always been a leader in military contracts. This all but explodes (pun intended) the myth of the autonomous pioneer. For every Apple in California, there is a Lockheed. Considering Silicon Valley is the domain of the cyberhippie-turned-capitalist culture, there is a deep irony in the fact that people who were once anti-war demonstrators have built an entire industry on the shoulders of the military. The brushing over of this fact is yet another example of historical myopia.

But one can scarcely explore the ironies of this without acknowledging Siliwood's companion movement, the "Military Entertainment Complex." In the wake of military downsizing, many military contractors, scratching their heads and wondering "Who, but the military, can afford us?" turned to their liberal neighbors in Hollywood. The result is a whole series of hybrid technologies, some of which I have had the pleasure of participating in the development of. I rather enjoy the concept of forging weapons into ploughshares, especially since both of the military-cum-entertainment projects I have worked on consisted of nonviolent content. In spite of my staunchly pacifistic position, I have a tremendous amount of respect for the fact that none of this would be possible without the military. In a way, the military could be looked at as the front end of the technological adoption curve.

Adoption Curve

"The Californian Ideology" spends a good deal of time on the topic of technological determinism and elitism. In America, we call this the "adoption curve." Here's how it works: Technology is developed at tremendous capital expense. It is released on the market at exorbitant prices, prices that the "average" person cannot begin to afford. It is targeted to a certain demographic-affluent, young, educated, eager to impress themselves and each other. These are the people who "lead" the market. They run out and buy "the latest" thing, drop it in the trunk of their BMW's, and take it home to their house in Marin County while listening to the CD player in their trunk, perhaps having a phonecall in the car on the way. If and when enough of these " early adopters" invest in the technology, one of two things will happen. More often than not, the technology falls on its face for whatever reason and becomes obsolete, rendering the expensive device virtually useless. However, if the right combination of factors are present, and a certain saturation level is reached, then presto! The price begins to plunge, and the subsequent tiers of adoption trailers follow, and eventually, the technology becomes available and affordable on a mass level. This process can sometimes take years, and there is fairly consistent demographic sequence to this pattern. This is the general means by which technology achieves mass market penetration in the U.S. and these are the actual terms that are used to describe this.

On the one hand, this can be viewed as an elitist system. And in many respects it is. But the fact is that if the technology is really worthwhile, eventually, the cost will keep being pushed down until it becomes affordable on a mass level. And the people at the head of the adoption curve are the Social Capitalism & Autodidactic Communalism.

Celia Pearce <celiapearATaol.com>

The Californian Ideology

'Not to lie about the future is impossible and one can lie about it at will' - Naum Gabo

There is an emerging global orthodoxy concerning the relation between society, technology and politics. We have called this orthodoxy `the Californian Ideology' in honour of the state where it originated. By naturalising and giving a technological proof to a libertarian political philosophy, and therefore foreclosing on alternative futures, the Californian Ideologues are able to assert that social and political debates about the future have now become meaningless.

The California Ideology is a mix of cybernetics, free market economics, and counter-culture libertarianism and is promulgated by magazines such as WIRED and MONDO 2000 and preached in the books of Stewart Brand, Kevin Kelly and others. The new faith P has been embraced by computer nerds, slacker students, 30-something capitalists, hip academics, futurist bureaucrats and even the President of the USA himself. As usual, Europeans have not been slow to copy the latest fashion from America. While a recent EU report recommended adopting the Californian free enterprise model to build the 'infobahn', cutting-edge artists and academics have been championing the 'post-human' philosophy developed by the West Coast's Extropian cult. With no obvious opponents, the global dominance of the Californian ideology appears to be complete.

On superficial reading, the writings of the Californian ideologists are an amusing cocktail of Bay Area cultural wackiness and in-depth analysis of the latest developments in the hi-tech arts, entertainment and media industries. Their politics appear to be impeccably libertarian - they want information technologies to be used to create a new `Jeffersonian democracy' in cyberspace in its certainties, the Californian ideology offers a fatalistic vision of the natural and inevitable triumph of the hi-tech free market.

Saint McLuhan

Back in the 60s, Marshall McLuhan preached that the power of big business and big government would be overthrown by the intrinsically empowering effects of new technology on individuals. The convergence of media, computing and telecommunications would inevitably result in an electronic direct democracy - the electronic agora - in which everyone would be able to express their opinions without fear of censorship.

Encouraged by McLuhan's predictions, West Coast radicals pioneered the use of new information technologies for the alternative press, community radio stations, home-brew computer clubs and video collectives.

During the '70s and '80s, many of the fundamental advances in personal computing and networking were made by people influenced by the technological optimism of the new left and the counter-culture. By the '90s, some of these ex-hippies had even become owners and managers of high-tech corporations in their own right and the pioneering work of the community media activists has been largely recuperated by hi-tech commerce.

The Rise of the Virtual Class

Although companies in these sectors can mechanise and sub-contract much of their labour needs, they remain dependent on key people who can research and create original products, from software programs and computer chips to books and tv programmes. These skilled workers and entrepreneurs form the so-called 'virtual class': '...the techno-intelligentsia of cognitive scientists, engineers, computer scientists, video-game developers, and all the other communications specialists...' (Kroker and Weinstein). Unable to subject them to the discipline of the assembly-line or replace them by machines, managers have organised such intellectual workers through fixed-term contracts. Like the 'labour aristocracy' of the last century, core personnel in the media, computing and telecoms industries experience the rewards and insecurities of the marketplace. On the one hand, these hi-tech artisans not only tend to be well-paid, but also have considerable autonomy over their pace of work and place of employment. As a result, the cultural divide between the hippie and the organisation man has now become rather fuzzy. Yet, on the other hand, these workers are tied by the terms of have no guarantee continued employment. Lacking the free time of the hippies, work itself ho become the main route to self-fulfilment for much of the,virtual class'.

Because these core workers are both a privileged part of the labour force and heirs of the radical ideas of the community media activists, the Californian Ideology simultaneously reflects the disciplines of market economics and the freedoms of hippie artisanship. This bizarre hybrid is only made possible through a nearly universal belief in technological determinism. Ever since the '60s, liberals -in the social sense of the word - have hoped that the new information technologies would realise their ideals. Responding to the challenge of the New Left, the New Right has resurrected an older form of liberalism: economic liberalism. In place of the collective freedom sought by the hippie radicals, they have championed the liberty of individuals within the marketplace. From the `70s onwards, Muffler, de Sola Pool and other gurus attempted to prove that the advent of hypermedia would paradoxically involve a return to the economic liberalism of the past. This 'retro-utopia echoed the predictions of Asimov, Heinlein and other macho sci-fi novelists whose future worlds were always filled with space traders, superslick salesmen, genius scientists, pirate captains and other rugged individualists. The path of technological progress leads back to the America of the Founding Fathers.

Agora or Exchange - Direct Democracy or Free Trade?

With McLuhan as its patron saint, the Californian ideology has emerged from this unexpected collision of right-wing neo-liberalism, counter- culture radicalism and technological determinism - a hybrid ideology with all its ambiguities and contradictions intact. These contradictions are most pronounced in the opposing visions of the future which it holds simultaneously.

On the one side, the anti-corporate purity of the New Left has been preserved by the advocates of the 'virtual community'. According to their guru, Howard Rheingold, the values of the counter-culture baby boomers will continue to shape the development of new information technologies.

Community activists will increasingly use hypermedia to replace corporate capitalism and big government with a hi-tech 'gift economy' in which information is freely exchanged between participants. In Rheingold's view, the 'virtual class' is still in the forefront of the struggle for social liberation. Despite the frenzied commercial and political involvement in building the 'information superhighway', direct democracy within the electronic agora will inevitably triumph over its corporate and bureaucratic enemies.

On the other hand, other West Coast ideologues have embraced the laissez faire ideology of their erstwhile conservative enemy. For example, Wired - the monthly bible of the 'virtual class' - has uncritically reproduced the views of Newt Gingrich , the extreme-right Republican leader of the House of Representatives, and the Tofflers, who are his close advisors. Ignoring their policies for welfare cutbacks, the magazine is instead mesmerised by their enthusiasm for the libertarian possibilities offered by new information technologies. Gingrich and the Tofflers claim that the convergence of media, computing and telecommunications will not create an electronic agora, but will instead lead to the apotheosis of the market, an electronic exchange within which everybody can become a free trader.

In this version of the Californian Ideology, each member of the 'virtual class' is promised the opportunity to become a successful hi-tech entrepreneur. Information technologies, so the argument goes, empower the individual, enhance personal freedom, and radically reduce the power of the nation-state. Existing social, political and legal power structures will wither away to be replaced by unfettered interactions between autonomous individuals and their software. These restyled McLuhanites vigorously argue that big government should stay off the backs of resourceful entrepreneurs who are the only people cool and courageous enough to take risks. Indeed, attempts to interfere with the emergent properties of technological and economic forces, particularly by the government, merely rebound on those who are foolish enough to defy the primary laws of nature. The free market is the sole mechanism capable of building the future and ensuring a full flowering of individual liberty within the electronic circuits of Jeffersonian cyberspace. As in Heinlein's and Asimov's sci-fi novels, the path forwards to the future seems to lead backwards to the past.

The Myth of the Free Market

Almost every major technological advance of the last two hundred years has taken place with the aid of large amounts of public money and under a good deal of government influence. The technologies of the computer and the Net were invented with the aid of massive state subsidies. For example, the first Difference Engine project received a British Government grant of £517,470 - a small fortune in 1834. From Colossus to EDVAC, from flight simulators to virtual reality, the development of- computing has depended at key moments on public research handouts or fat contracts with public agencies. The IBM corporation built the first programmable digital computer only after it was requested to do so by the US Defense Department during the Korean War. The result of a lack of state intervention meant that Nazi Germany lost the opportunity to build the first electronic computer in the late '30s when the Wehrmacht refused to fund Konrad Zuze, who had pioneered the use of binary code, stored programs and electronic logic gates.

One of the weirdest things about the Californian Ideology is that the West Coast itself is a product of massive state intervention. Government dollars were used to build the irrigation systems, high-ways, schools, universities and other infrastructural projects which make the good life possible. On top of these public subsidies, the West Coast hi-tech industrial complex has been feasting off the fattest pork barrel in history for decades. The US government has poured billions of tax dollars into buying planes, missiles, electronics and nuclear bombs from Californian companies. Americans have always had state planning, but they prefer to call it the defence budget.

All of this public funding has had an enormously beneficial - albeit unacknowledged and uncosted - effect on the subsequent development of Silicon Valley and other hi-tech industries. Entrepreneurs often have an inflated sense of their own 'creative act of will' in developing new ideas and give little recognition to the contributions made by either the state or their own labour force. However, all technological progress is cumulative - it depends on the results of a collective historical process and must be counted, at least in part, as a collective achievement. Hence, as in every other industrialised country, American entrepreneurs have in fact relied on public money and state intervention to nurture and develop their industries. When Japanese companies threatened to take over the American microchip market, the libertarian computer capitalists of California had no ideological qualms about joining a state-sponsored cartel organised by the state to fight off the invaders from the East!

Masters and Slaves

Despite the central role played by public intervention in developing hypermedia, the Californian Ideology is a profoundly anti-statist dogma. The ascendancy of this dogma is a result of the failure of renewal in the USA during the late '60s and early '70s. Although the ideologues of California celebrate the libertarian individualism of the hippies, they never discuss the political or social demands of the counter-culture. Individual freedom is no longer to be achieved by rebelling against the system, but through submission to the natural laws of technological progress and the free market. In many cyberpunk novels and films, this asocial libertarianism is expressed by the central character of the lone individual fighting for survival within a virtual world of information.

In American folklore, the nation was built out of a wilderness by free-booting individuals - the trappers, cowboys, preachers, and settlers of the frontier. Yet this primary myth of the American republic ignores the contradiction at the heart of the American dream: that some individuals can prosper only through the suffering of others. The life of Thomas Jefferson - the man behind the ideal of `Jeffersonian democracy' - clearly demonstrates the double nature of liberal individualism. The man who wrote the inspiring call for democracy and liberty in the American declaration of independence was at the same time one of the largest slave-owners in the country.

Despite emancipation and the civil rights movement, racial segregation still lies at the centre of American politics - especially in California. Behind the rhetoric of individual freedom lies the master's fear of the rebellious slave. In the recent elections for governor in California, the Republican candidate won through a vicious anti-immigrant campaign. Nationally, the triumph of Gingrich's neoliberals in the legislative elections was based on the mobilizations of "angry white males" against the supposed threat from black welfare scroungers, immigrants from Mexico and other uppity minorities.

The hi-tech industries are an integral part of this racist Republican coalition. However, the exclusively private and corporate construction of cyberspace can only promote the fragmentation of American society into antagonistic, racially-determined classes. Already 'redlined' by profit-hungry telcos, the inhabitants of poor inner city areas can be shut out of the new on-line services through lack of money. In contrast, yuppies and their children can play at being cyberpunks in a virtual world without having to meet any of their impoverished neighbours. Working for hi-tech and new media corporations, many members of the 'virtual class' would like to believe that new technology will somehow solve America's social, racial and economic problems without any sacrifices on their part. Alongside the ever-widening social divisions, another apartheid between the 'information-rich' and the 'information-poor' is being created. Yet calls for the telcos to be forced to provide universal access to the information superstructure for all citizens are denounced in Wired magazine as being inimical to progress. Whose progress?

The Dumb Waiter

As Hegel pointed out, the tragedy of the masters is that they cannot escape from dependence on their slaves. Rich white Californians need their darker-skinned fellow humans to work in their factories, pick their crops, look after their children and tend their gardens. Unable to surrender wealth and power, the white people of California can instead find spiritual solace in their worship of technology. If human slaves are ultimately unreliable, then mechanical ones will have to be invented. The search for the holy grail of Artificial Intelligence reveals this desire for the Golem - a strong and loyal slave whose skin is the colour of the earth and whose innards are made of sand. Techno-utopians imagine that it is possible to obtain slave-like labour from inanimate machines. Yet, although technology can store or amplify labour, it can never remove the necessity for humans to invent, build and maintain the machines in the first place. Slave labour cannot be obtained without somebody being enslaved. At his estate at Monticello, Jefferson invented many ingenious gadgets - including a 'dumb waiter' to mediate contact with his slaves. In the late twentieth century, it is not surprising that this liberal slave-owner is the hero of those who proclaim freedom while denying their brown-skinned fellow citizens those democratic rights said to be inalienable.

Foreclosing the Future

The prophets of the Californian Ideology argue that only the cybernetic flows and chaotic eddies of free markets and global communications will determine the future. Political debate therefore, is a waste of breath. As libertarians, they assert that the will of the people, mediated by democratic government, is a dangerous heresy which interferes with the natural and efficient freedom to accumulate property. As technological determinists, they believe that human social and emotional ties obstruct the efficient evolution of the machine. Abandoning democracy and social solidarity, the Californian Ideology dreams of a digital nirvana inhabited solely by liberal psychopaths.

There are Alternatives

Despite its claims to universality, the Californian ideology was developed by a group of people living within one specific country following a particular choice of socio-economic and technological development. Their eclectic blend of conservative economics and hippie libertarianism reflects the history of the West Coast - and not the inevitable future of the rest of the world. The hi-tech ideologues proclaim that there is only one road forward. Yet, in reality, debate has never been more possible or more necessary. The Californian model is only one among many.

Within the European Union, the recent history of France provides practical proof that it is possible to use state intervention alongside market competition to nurture new technologies and to ensure their benefits are diffused among the population as a whole.

Following the victory of the Jacobins over their liberal opponents in 1792, the democratic republic in France became the embodiment of the 'general will'. As such, the state attempted to represent the interests of all citizens, rather than just protect the rights of individual property-owners. The French revolution went beyond liberalism to democracy. Emboldened by this popular legitimacy, the government was able to influence industrial development.

For instance, the MINITEL network built up its critical mass of users through the nationalised telco giving away free terminals. Once the market had been created, commercial and community providers were then able to find enough customers to thrive. Learning from the French experience, it would seem obvious that European and national bodies should exercise more precisely targeted regulatory control, investment, and state direction over the development of hypermedia, rather than less.

The lesson of MINITEL is that hypermedia within Europe should be developed as a hybrid of state intervention, capitalist entrepreneurship and d.i.y. culture. No doubt the 'infobahn' will create a mass market for private companies to sell existing information commodities - films, tv programmes, music and books, across the Net. Once people can distribute as well as receive hypermedia, a flourishing of community media, niche markets and special interest groups will emerge. However, for all this to happen the state must play an active part. In order to realise the interests of all citizens, the 'general will' must be realised, at least partially, through public institutions.

The Californian Ideology rejects notions of community and of social progress and seeks to chain humanity to the rocks of economic and technological fatalism. Once upon a time, west coast hippies played a key role in creating our contemporary vision of social liberation. As a consequence, feminism, drug culture, gay liberation and ethnic identity have, since the 1960s, ceased to be marginal issues. Ironically, it is now California which has become the centre of the ideology which denies the relevance of these new social subjects.

It is now necessary for us to assert our own future - if not in circumstances of our own choosing. After twenty years, we need to reject once and forever the loss of nerve expressed by post-modernism. We can do more than 'play with the pieces' created by avant-gardes of the past.

We need to debate what kind of hypermedia suit our vision of society - how we create the interactive products and on-line services we want to use, the kind of computers we like and the software we find most useful. We need to find ways to think socially and politically about the machines we develop. While learning from the can-do attitude of the Californian individualists, we also must recognise that the potentiality of hypermedia can never solely be realised through market forces. We need an economy which can unleash the creative powers of hi-tech artisans. Only then can we fully grasp the Promethean opportunities of hypermedia as humanity moves into the next stage of modernity.

Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron are members of the Hypermedia Research Centre, University of Westminster

Proliferating Futures (Re: Californian Ideology)

Re: Californian Ideology

1: Proliferating Futures What about the Becoming of the Net? We cannot describe the Net as one single process of Becoming, but as proliferation of different coexisting processes. Therefore we can't make a statement about the future of the Net. Many different futures will coalesce within it.

Different intentions can enter the Net, different processes of semiotization can coevolute. The Net is not a territory, but a multiplanary Sphere. Infinite plateaux are rotating inside this Sphere. What is forbidden on one level can be done on another.

The Net cannot be conceptualized within the Hegelian concept of Totality. In Hegel, the Truth is the Whole. The Hegelian Whole is Aufhebung - the annihilation of every difference. In the Net, every connection between points of enunciation creates its own level of truth. Truth is only found in singularity.

In the Net, the world cannot be considered as the objective reference point of a process of enunciation. The world is the projection of enunciation itself.

Networking is the method of a new social paradigm - one that goes beyond the social oppositions and conceptual contradictions inherited from the modern world. Because capitalism is still in power, acting as the general semiotic code, the old social oppositions and conceptual contradictions are not vanishing yet. This is the reason why we are still concerned with the old problem of the State versus the Market. Notwithstanding the emergence of the Net, the State and the Market still exist.

2: High Tech Deregulation

The discourse about the Net (cyberculture) is still dominated by ideologies which are the legacy of the past twentieth century. Cyberculture is still dominated by the conceptual and political alternatives coming from the industrial society. A sort of high tech neo-liberalism is emerging from the American scene. In the theoretical core of this philosophical movement, I see a misunderstanding: the identification of technology with economics within the paradigm shift. Thinkers like Alvin Toffler, Kevin Kelly and Esther Dyson support the neo-liberal agenda of Newt Gingrich because, they argue, the free market is the best method for expanding free communications - and free communications are the key to the future world.

Sounds good, but what does the 'free market' mean? In the social framework of capitalism, free market means power to the strongest economic groups - and the absorption or elimination of society's intellectual energies.

Kevin Kelly, in 'Out of Control', says that, thanks to the digital technologies and computer networks, mankind is evolving into a superorganism, a new biological system. The biologisation of culture and society which is described by Kelly is nothing but the disappearance of any alternative from the social field, the absorption of intelligence itself within the framework of capitalist semiotization. The possibility of choice is denied, eradicated.

This is the main effect of the integration of technological development, scientific work and economic power. Michel Foucault describes the formation of modern society in terms of the imposition of discipline on the individual body and on social behaviour. What we are now witnessing is the making of what Gilles Deleuze defines as a society of control: the code of behaviour is being imprinted directly onto the mind through models of cognition, of psychic interaction. Discipline is no longer imposed on the body through the formal action of the law - it is printed in the collective brain through the dissemination of techno-linguistic interfaces inducing a cognitive mutation.

3: Old Alternatives are Misleading

In their article 'The Californian Ideology', Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron criticize the mystification of this high tech neo-liberalism. But what do they oppose it with? They talk of a European way - the way of the welfare state, public intervention within the economy, public control over technological innovation. Can we believe in this solution? I don't.