Crisis at the ICA: Ekow Eshun's Experiment in Deinstitutionalisation

Amidst a general acceptance of the cash crisis afflicting the ICA as an accident of the recession, and a rush into ‘hairshirt' institutional self-critique as a means to deflect real scrutiny, JJ Charlesworth uncovers a catalogue of avoidable mistakes and the free-market, lifestyle thinking behind them

In the last few weeks press reports have begun to appear regarding the growing financial crisis besetting London's Institute of Contemporary Arts. On the 22 January, the Guardian reported that ‘Staff members have been told that a financial deficit currently at around £600,000 might rise to £1.2m and if radical steps are not taken the ICA could be closed by May.' A week later, the Times quoted an ICA spokeswoman who confirmed as a ‘fair estimate' that ‘a third of its full-time staff of "around 60" would be in line for redundancy.'

Ekow Eshun, the ICA's artistic director since 2005, told the Guardian that the ICA's financial problems emerged as a result of a ‘perfect storm of events that all came together'. Income from fundraising, from trading income and from the ICA's film distribution arm, have ‘also suffered because of the recession.'

So far, the mainstream press has accepted this rather glib account of inevitable woe caused by the recession. In the fatalistic and passive terms that currently dominate any discussion about the recession, there is apparently nothing that anyone can do about the ICA's financial troubles; the recession is seen as a force of nature, and everyone is quick to accept Eshun's catchy characterisation of the ICA's crisis as a ‘perfect storm'. So instead of asking how exactly the ICA has got into such a mess, mainstream press coverage has typically discovered another opportunity to beat-up on the ICA, and to carp about whether the ICA should be left to fail; ‘should we let the ICA die?' was the Times' dismissive headline.

That so little interest has been paid to the precise circumstances of the ICA's troubles is disturbing. Merely accepting that ‘the recession is to blame' leaves bigger questions unanswered both about the ICA's artistic and financial governance over the last five years, but also of broader issues of state funding policy towards private sector involvement in the financing of arts organisations, while making no one accountable for the roots of these failures. A closer look at the recent history of the ICA suggests a number of serious issues that have consequences not only for the future of the organisation itself, but also for the broader sector of state funded arts organisations.

In October 2009, Arts Council England awarded the ICA £1.2 million over two years from its Sustain emergency budget, ear-marked for arts organisations suffering from the effects of the recession. This is the second largest of the grants made from the fund (only the Yorkshire Sculpture Park has been granted more). As part of this emergency package a consultant, ex-curator David Thorp, had been hired to conduct an organisational review of the ICA's activities and structures. On 10 December 2009 staff were called to a meeting with Eshun and members of the ICA's governing council, including chairman Alan Yentob. In minutes of that meeting seen by the Guardian and by Mute, staff were told about the need to slash the £2.5 million salary budget by £1m, and drastically reduce the ICA's programming, particularly the cinema's programme. An organisational restructure outline also seen by Mute proposes closing the ICA to the public two days a week. According to Eshun, the proposed new programme would operate only in the lower exhibitions gallery.

In what was clearly a heated and bad tempered debate, Eshun and Yentob continually insisted that the cash crisis was down to ‘shortcomings' in the Development department, the bookshop and ICA films. Clearly defensive, Eshun argued that it was not always easy to make correct estimates, but that while this could be seen to be a result of decisions made by Eshun and Guy Perricone (Eshun's managing director, an ex-banker who finally resigned in October 2009, having been appointed shortly after Eshun in August 2005) there were ‘structural problems' that needed addressing. Remarkably, Eshun concluded that he was the best person to take the ICA ‘into the future'.

But the assertion that the ICA's financial difficulties are uniquely a product of the current recession does not seem to be supported by a review of the organisation's published finances in the years prior to the recession, and during the boom years of Eshun's tenure, since his appointment in May 2005. The ICA's accounts are publicly available through the Charities Commission. What they reveal is an organisation which, while faring relatively well from its programming income, became dangerously dependent on a high-risk strategy of developing what turned out to be volatile and unpredictable income from sponsorship deals. A later decision to remove entrance fees was to prove similarly damaging.

Under Eshun, the ICA went from an income of just over £3.75 million in 2005 to just over £5 million by 2008. The ICA's Arts Council grant might have increased by £70,000 between 2006 and 2008, but the most significant change was in the generation of sponsorship income. In 2006 total sponsorship amounted to £306,000. In 2007 this leapt to £970,000. (It was also in early 2007 that the ICA sold off its Picasso mural to the Wellcome Trust for £250,000.) And in 2008 the ICA made £756,000 in sponsorship.

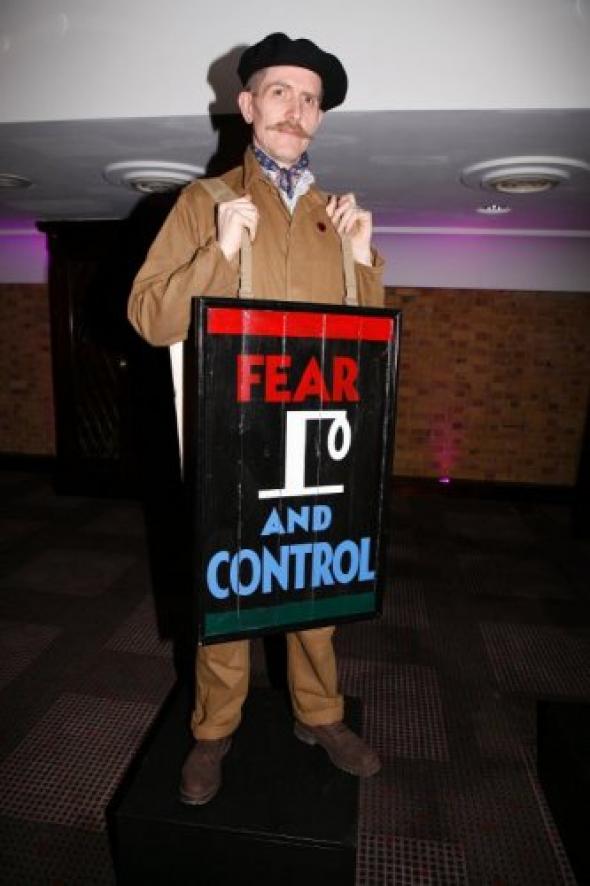

Image: The man with the plan. Ekow Eshun at the AmbITion roadshow, Sadler’s Wells Theatre, 16th July, 2009

Such large increases were achieved by a new sponsorship led policy, hiring new development and marketing staff tasked with developing high profile sponsorship events that prioritised the ICA ‘brand' as a whole, rather than supporting any individual programming department. Not surprisingly, the ICA's wage bill in the period ballooned, from £1.75 million in 2005 to £2.5 million in 2008, although the ICA's accounts report an increase in average staff headcount of only 13. The number of staff paid more than £50,000 rose from three to ten in that period.

If the ICA was riding high on the sponsorship gravy train, more non-programming staff and bigger salaries for those at the top, this was based on marketing projects increasingly untethered from the ICA's core programme content, but instead plugged in to a newer, ‘hipper' notion of the ICA as an arbiter of contemporary cool, all the while attempting to harness the spend power of celebrity, and the success-by-association of a heightened media profile. Instead of raising income for the projects of particular departments - Cinema, Exhibitions, Live and Media Arts, and Talks - all energies became focused on ‘general projects' drawing big cheques from big corporates. In 2007, a Sony PSP hook-up generated £95,000, a deal with 3G mobile netted £150,000, and the Sony Ericsson backed image anthology and contest All Tomorrow's Pictures earned the ICA £228,000. By 2007, ICA Development had initiated the annual celeb-driven charity auction gala night Figures of Speech. The 2008 edition, attended by such art world luminaries as Nigella Lawson, Tom Dixon and Elle McPherson, rang up £126,000 in the process.

Such sponsorship arrangements are inherently fast burning and short term. Particularly alarming, in this regard, has been the involvement of a more unstable variety of business partners for the ICA's sponsorship projects, and the closeness of those businesses to the ICA's governing council. In 2008 and 2009, the Figures of Speech gala was sponsored by troubled voicemail-to-text message dotcom startup SpinVox. In 2008, SpinVox paid £128,000 for its association with the gala night. While no figures are yet published for the March 2009 edition (also in association with SpinVox), press details released by the ICA record auction results of £86,000, but refer to a headline figure of £180,000 raised by the event, suggesting a similar involvement by SpinVox.

By summer 2009, the £100 million start-up had run out of cash. In December, it was sold to American speech-recognition company Nuance for £64 million. SpinVox's vice-president for consumer business is James Scroggs. Scroggs was also listed as one of the board of directors of the ICA company, appointed in September 2006.

Equally unfortunate was the sponsorship involvement of GuestInvest, the buy-to-let hotel property investor (slogan: ‘earn money while others sleep') which had paid £88,000 for a project called ICA TV: London Now, branded ICA video content for hotel TVs. GuestInvest went into administration in October 2008. Its CEO was Johnny Sandelson, who was also a member of the ruling council of the ICA and one of the directors, appointed in October 2007, and who resigned in October 2008. GuestInvest still owes the ICA £33,000.

There are other mistakes not due to the recession. The incautious decision, in September 2008, not long before the Lehman Brothers collapse and the start of the credit crunch proper, to abolish the day membership fee put a further squeeze on income. Sources suggest that the abolition of day membership may have accounted for at least £120,000 in lost revenue to the ICA. And with the abolition of the day-membership, annual membership subscriptions are reported to have declined significantly during 2009.

The picture that emerges is of an organisation in which costs inflated against projected income, based on a marketing model framed by increasingly unrealistic income projections, which left the ICA more exposed to the peculiarly erratic and hard to sustain income streams derived from the marketing budgets of big corporates, the quickly exhausted favour of professional contacts among directors, and the fickle interest of celebrity benefactors. Quite how exposed the ICA became by early 2009 is not clear, but the general experience of the marketing and advertising staff, especially those dealing with brand sponsorship, suggests that many marketing budgets evaporated as brands panicked as the credit crunch hit in earnest in late 2008. But already in early 2008, Mark Sladen, director of exhibitions, was reportedly furious at the Development department's failure to secure any substantial sponsorship for the sixtieth anniversary exhibitions programme ‘Nought to Sixty', which ran from May to October 2008. The season culminated with a 60th anniversary auction of work. But with the credit crunch, the game was already over and the auction raised £673,000, failing to realise the £1.3m the ICA had hoped for. Public commitments that revenue from the ICA auction should help establish a commissioning fund for emerging artists were quietly shelved, the proceeds instead directed into the ICA's general funds. Between deluded projections of high-risk income and the undermining of core revenue streams, it may have been a ‘perfect storm', but someone was sailing the ship towards it.

But like Gordon Brown's attitude to his handling of the British economy prior to the recession, Eshun seems convinced that he bears no responsibility for the ICA's recent trajectory, nor its media-dazzled artistic policy, and is now the best person to come to its rescue. Indeed, it seems that for Eshun, Yentob and perhaps secretly even the Arts Council, the financial crisis at the ICA offers an ideal opportunity to spin the current troubles into a story of renewal, with Eshun at the helm. After all, one of the criticisms regularly levelled at the ICA by hostile critics is that the institution is ‘no longer relevant'.

Eshun is the ICA's own best critic, of course. At the 10 December meeting, he repeated his mantra that ‘all multi-arts spaces are re-thinking what they need to do. The post-war modernist presentation of art is no longer relevant and the ICA needs a vision for what this means.'

Eshun's ‘vision' has been long in coming. In a ‘vision' document circulated in Spring 2009, Eshun wrote that a key challenge for the ICA was how it might ‘update the traditional model of the arts centre with its silo-like programming structure.' The new vision was to be one of fluidity, flexibility, spontaneity and itinerant programming, taking its cue from the model of biennials, fairs and festivals, each of which offered ‘a more fluid and decentred model of arts presentation with a focus on new commissions.' The ICA could ‘occasionally work in a similar spirit, reconfiguring ourselves as a sometime festival, a freeform space of artistic exploration dedicated to articulating a particular mood or movement.'

But what does updating the ‘silo-like' programming structure of the arts centre and seeking a ‘more fluid and decentred model of arts presentation' actually mean in practice? One might argue that Eshun's antagonism towards the ‘post-war modernist art centre' would seem to run contrary to the ICA's 1947 founding charitable objects:

To promote the education of the community by encouraging the understanding, appreciation and development of the arts generally and particularly of contemporary art as expressed in painting, etching, engraving, drawing, poetry, philosophy, literature, drama, music, opera, ballet, sculpture, architecture, designs, photography, films, radio and television of educational and cultural value.

Of course, a set of artistic designations as antique as these needs periodic updating; nor does it prescribe the form or structure an organisation should take to deliver such a programme. But Eshun's fascination with the temporary, the flexible and the decentred, of a cultural outlook in which nothing is permanent, was translated into a managerial policy of wearing down the ‘silo-like' departmental programming structure of the organisation, at the cost of a loss of curatorial expertise. In October 2008, Eshun decided to abolish the ICA's Live and Media Arts department, a decision which drew acrimonious responses by practitioners in the live and media arts community. And with the resignation of the Talks department in December 2009, increasingly, the responsibility for any original programming fell to exhibitions, the only programming department to have enjoyed any significant budget increase under Eshun's directorship.

Image: Hot Chip 'Shake a Fist' at the cruel fates at the All Tomorrow's Pictures party, ICA, May 2007

There is of course another term to describe the process occurring in this new ‘decentred' art centre. It is ‘de-skilling'. The vision of a fluid, flexible, temporary institution is, ironically, entirely concomitant with a general trend towards bureaucratisation and the abolition of expertise in organisational structures that mediate between cultural practitioners and arts policy. This has been vividly evident in the changes in arts funding bodies in recent years. For example, the removal of art-form specific advisory panels was an early innovation at Arts Council England under New Labour. A similar process destroyed the British Council's artistic departments in late 2007, when it disbanded its film, drama, dance, literature, design and visual arts departments, amalgamating them into a single ‘arts team', organised around bizarre management aphorisms such as ‘Progressive Facilitation', ‘Market Intelligence Network', ‘Knowledge Transfer Function' and ‘Modern Pioneer'. In both organisations, the political instinct has been bureaucratic; to withdraw authority and independence from staff appointed for their knowledge of a particular field of artistic practice, in order to better administer whatever policy imperative happens to be coming from central government.

But the hostility of bureaucrats to independent cultural expertise can also be mapped onto the apparently cutting-edge curatorial privileging of flexible, ad hoc programming, and both have the same useful managerial outcomes: fewer staff and more precarious, temporary employment contracts. The disdain for expertise within arts policy thinking also reflects a cynical lack of commitment to the independence of cultural forms, a trivialising indifference to the value those forms have achieved, and an obsession with the mobile tastes of ‘the public' as the final arbiter of cultural value. In Eshun's hyperventilating vision document he asks which ‘faces should most accurately represent the ICA now?' He concludes:

It should be the artistic figures that our audience admires... We should celebrate them in our communications as our heroes, our star names already, because our audience believes they are cool. And we should keep in mind that in a week to a year hence, many of those figures will no longer be relevant because there will be a new set or more urgent names to hail. All that matters is now.

With a rate of artistic redundancy as fast as this, you don't need curatorial expertise, or an opinion regarding what art is worth supporting and championing - you just need Simon Cowell.

Such abdication of curatorial authority to the audience presupposes that what the audience wants is merely what the institution should do. It does not acknowledge that a presenting institution such as the ICA might have a relationship to communities of artistic practice that have distinct cultural and organisational histories, and their own attendant audiences. Such distinctions cannot simply be wished away by a bit of re-imagineering of a cultural mission statement. If the artistic relevance of the ICA has reputedly dwindled during Eshun's tenure, it perhaps has something to do with how an emptied-out model of audience feedback and ‘early-adopter' trend-following became a substitute for agenda-setting, or a critical vision of the current state of art and culture, or real artistic-curatorial relationships with different artistic and cultural communities.

This is not an argument against ‘cross-disciplinarity', but it is an argument for the fact that ‘cross-disciplinarity' requires the reality of a disciplinary base for practice in the first instance. Forms of artistic creativity are not in constant flux or transformation (though they do change historically) but coalesce into sustained practices and communities of artists and audiences. This is not an outdated ‘mode' of the ‘post-war modernist art centre', but a recognition that a venue may play host to multiple artistic cultures and communities, which it is not wholly instrumental in generating and sustaining. By contrast, the tendency to abolish programming departments rids an organisation of staff with expertise and commitment to particular fields of activity. It is a move which denies the autonomy of different artistic fields as they already exist outside of the institution, and turns the institution's role from that of forum and enabler for those communities, to a regulator of which artistic practice gains visibility. In other words, it reduces the claim that communities of artistic practitioners can make on cultural institutions, and elevates the institution's arbitrary power over artists by distancing itself from already present communities of practice.

Eshun's blithe comment at the time the closure of the Live and Media Arts department - that new media-based arts practice ‘lacks cultural urgency' - is indicative of this confusion between fluid, non-disciplinary notions of curatorial agency, trend-setter indifference to anything that is not ‘now' and the bureaucratic tendency to withdraw from contacts with practitioners. It wasn't that there wasn't a lively culture of artistic work being done in live and media arts at the time, but simply that a cultural director had passed judgement that it was no longer relevant. But such an approach is not surprising; Eshun's previous jobs were as editor of the now defunct Arena, the men's style magazine, and before that assistant editor of the equally defunct The Face. Observing, selecting, picking-and-mixing, schmoozing the culture in the name of what's cool one moment and not cool the next, are the necessary attributes of mass-media cultural commentators and style arbiters. But they comprise an outlook at odds with negotiating a more complex relationship between artists and the support an institution can bring. The ‘flexible institution' is in fact one detached from any relationship of commitment to the art-form communities it has a mission, in part, to represent.

Image: Natasha Plowright, Alan Yentob and Graham Norton at the Figures of Speech Gala, ICA, February 2008

There is another twist to the ICA's current crisis. Prior to the staff meeting of 10 December, the exhibitions department had organised a day-long meeting of invited artists and curators, to discuss a proposed emergency programme project with the working title of the The Reading Group:

From May 2010 to April 2011 the ICA will undertake an experiment in de-institutionalisation, prototyping a lightweight, responsive arts organisation able to cope with more straitened and complicated times. This will be a time-limited project, exactly a year in duration, during which period the ICA will cease many of its regular activities, and instead play host to a temporary research forum or think tank, addressing a range of urgent questions.

The Reading Group, declared a draft outline of the project, is ‘designed to create a space where artists, writers, thinkers and others can come together, share research and work collaboratively, taking the model of The Reading Group as an ideal for temporary communal investigation.'

With the ICA facing one of the most serious financial crises in its 63-year existence, its programme for the next year appears to be a radical-sounding ‘experiment in de-institutionalisation', with radical artists and academics co-opted to provide content on a shoestring budget. For fans of grotesque irony The Reading Group outline is unmatched reading; couched in the contemporary terminology of anti-capitalism and art-institutional critique, The Reading Group is slated to address several themes, including ‘What work can we do?' (investigating ‘alternative ways of thinking about production and labour'), and ‘How can we act collectively?' (exploring ‘the role of institutions such as the ICA in enabling communal action.') A wish list of cutting-edge artists and academics including Antonio Negri, Hito Steyerl and Eyal Weizman suggests the tenor of the programme.

The Reading Group meeting was attended by a number of curators from European institutions, among them Amsterdam's De Appel, Barcelona's MACBA and Antwerp's Objectif. As one London attendee put it, the general tone of the meeting was always to see questions of financial crisis as an opportunity for a radicalised programme and an opportunity to get ‘back to basics'.

Such ‘hairshirt radicalism' is common to the confused cultural response to the broader economic crisis. So much of the ‘critical' art world has spent the last decade decrying the market boom that it now seems to see the recession as a sort of degraded Marxian ‘comeuppance' for the apparent excesses of western consumer capitalism. Because of the general distaste with which ‘commodity' art has been held during the boom, it seems those practices which spent the boom decrying the venality of market-driven art, might now be eagerly co-opted as useful filler for institutions no longer able to sustain more costly public programmes. Talk is cheap after all, as are galleries full of tables and chairs, stuff to read and endless discussions to be had about radical projects, conducted by unpaid artists. But as The Reading Group attendee suggested, the only radical discussion not on the table was the only one worth having - how did we get here?

But the crisis at the ICA should be a banal one - it is about dumb financial issues, even dumber management and a precarious and delusional faith in the frothy economics of the boom-time ‘creative industries'. Pretending that it is, now, a crisis in the ideological and cultural form of the institution is to provide cultural bureaucrats at ACE and the DCMS with the mission statement to justify the down-sizing and overhaul of all other cultural institutions that run into trouble, while diverting the discussion from the broader politics of the recession. The governing council of the ICA is apparently ‘100% behind' Eshun. The Arts Council appears to support the current situation, declaring that it accepts

that the board and management have to make tough and potentially unpopular decisions if the ICA is going to become a sustainable organisation delivering strong artistic programmes, through a fit for purpose organisational structure and robust financial strategy.

The final decision on the release of the second half of the Sustain grant falls to the national council of ACE, though ACE strenuously insists that Eshun's membership of the national council will have no bearing on the decision.

But what of the staff of the ICA who stand to lose most in this debacle? Do they support Eshun? In early February, the staff council called a vote of no confidence in Eshun, but in a bizarre twist, the staff were called to vote on whether the vote of no confidence should be counted. The ICA denies that a vote of no confidence has taken place. Five years, it seems, is not long enough for Eshun's first ‘experiment in de-institutionalisation'.

JJ Charlesworth <jjcharlesworth AT artreview.com> is a freelance critic and associate editor of ArtReview magazine

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com