Chapter 9: Introduction - The Open Work

Introduction to Chapter 9 of Proud to be Flesh - The Open Work

—

Finally you are no more than an imitation of an actor.

Friedrich Nietzsche

The most radical potential stored in the phenomenon of ‘interactivity’ must be the redistribution of creativity away from the author and toward the user, the group, the crowd, the social. The potential to reproduce, and recombine, information into new forms is the other function of the computer that carries this potential, undermining the auratic original and making it available for endless redeployment. Post-structuralism’s critique of the author, ‘his’ reification and the concomitant eclipse of creativity’s social nature, coincides, to a great extent, with the advent of (networked) computing – and its implied assault on the originality and exclusivity of cultural objects. John Cage turned the sound of an audience, waiting in silence for a performance to begin, into a piece of music only a decade before J.C.R. Licklider presented his concept of an ‘Intergalactic Computer Network’. These distinct, and mutually disinterested, developments were, in fact, happening simultaneously, and would later become deeply entangled with one another. Largely through writing on music and sometimes on art, poetry and popular computing, this chapter follows these threads, to explore their knotty outcomes in ’90s and ’00s technoculture. Its writers ask how the ‘open work’ has fared, from its tender avant-garde beginnings to its reification in Web 2.0 and, debatably, its banalisation in relational aesthetics.

Flint Michigan, in his text ‘Composing Ourselves’, suggests that French music theorist, Jacques Attali’s expanded concept of ‘composition’ is, in part, a reworking of Marx’s idea of ‘really free working, e.g. composition’. This formulation is key to many of these articles because it strives to articulate a kind of making/doing that is free from the alien demands of capital, the imperative to produce for value’s sake. Attali’s concept of ‘composition’ is something that exists beyond the ‘rupture’ of changing economic and technological conditions, to reveal ‘the demand for the truly different system of organisation, a network within which a different kind of music and different social relations can arise’. Where Michigan takes issue with Attali is in his characterisation of this free working as ‘A music produced by each individual for himself, for pleasure outside meaning, usage and exchange’. The connection between the socially transformative powers of music and creativity are somehow folded back into the confines of individual enjoyment, rendering Attali’s concept paradoxical. Is it not incoherent to suggest that such ego-invested production challenges capitalism’s systems of ‘meaning, usage and exchange’ when it leaves the sign-value of the author intact?

Keston Sutherland’s lacerating account of the post-Soviet, poetic orthodoxy of the American L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E school – whose attacks on any ‘subjective expressiveness’ that can be ‘identified with the psychic operations […] of an ‘Author’ seems at first to clash with Michigan’s dismissal of the composer-as-Author. But, Sutherland further unpacks his suspicion of this poetic school and its ‘puritanical’ refusal to allow the ‘interpretative consumption’ of expressiveness. For Sutherland, these poets’ use of ‘debris-syntax’ and wilful deformation of language amounts to little more than a ‘consumer revolt’ against one of global capitalism’s most vital tools – English. So, rather than this amounting to an anti-avant-gardist defence of the Author, Sutherland deems these gestures to be not radical enough, mere tokens of rejection in the face of the persistence of ‘English-as-capitalism-logos’ – a consumer revolt rather than something that redistributes the means/meaning of production.

Luc Ferrari’s piece, Presque Rien No. 1, is discussed in Michigan’s second text in this chapter. His simple recording of a Croatian fishing village in the early hours of the morning, writes Michigan, sets the composer ‘alongside the listener’. The senses are freed from the responsibility to interpret authorial intention and left to an unfettered exploration of disembodied sounds, to engage in a ‘desiring perception’. The freedom created by Ferrari’s piece, which, at the same time, avoids musique concrète’s subsequent naturalism, stands in antithesis to mid-’90s signature interactive artwork, Osmose, by Char Davies. In their discussion of the piece, the Bureau of Inverse Technology (BIT) describe how the viewer is strapped into VR goggles and heavy, breath-sensitive equipment and then ‘released’, for a strict 20 minutes, to navigate through a floaty VR ‘mushspace’. Not only did the level of control and supervision surrounding the piece prevent any sense of voluntary exploration, but the supposed empowerment of the viewer was belied by Osmose’s ‘morphine haze of compulsive serenity’, its ‘force-gentling’. The piece’s declared ‘re-connection’ of virtuality and ‘wild nature’ is nothing but an audio-visual pacifier, burying the truth of technology’s relationship to ‘nature’ behind an insipid simulation.

In sharp distinction to this increasingly discredited genre of ‘interactivity’ – which finds its analogue in consultative politics’ pre-emptive neutralisation of resistance – are the man-machine relations of Detroit techno. In his interview with techno legend, Jeff Mills, Hari Kunzru describes how ‘Mills the DJ seems self-evidently a component of a human-machine assemblage, a system which includes crowd, PA, the whole apparatus of record production and the stylus cartridge […]’. And, later, Mills relates how, when programming a sequence, he sometimes goes out and just lets it run for up to 24 hours: ‘The machines fluctuate. Over time the sequence changes slightly. The machines mould themselves, giving their own character to a track.’ If Ferrari’s work set the composer alongside the listener, techno sets the composer and listener alongside the machine. The permutative power of computation, the warp of a specific machine, the impact of amplification and repetitive beats on a crowd, and the anti-naturalism of electronic sound are just some of the ways in which an ‘alien’ intelligence acts to disrupt the dyad of artist/viewer or composer/listener.

Of course, machinic propagation also has its down sides – something Paul Helliwell contemplates in his piece, ‘Zombie Nation’, in which he connects Web 2.0, relational aesthetics and the (commodity) crisis of the music industry. As he explains, music (and indeed capitalism) has started to resemble so-called relational aesthetics in the age of digital reproduction. He recounts how Attali joked at a record industry bash that, apart from gigs, in the age of free downloads, soon all that bands will be able to sell is the right to attend a rehearsal or go to dinner with them. As the music and other industries, such as publishing and software, lose control of the commodity, increasingly all that is left to sell are relations between people, in different spatial and temporal arrangements. The culture industry, argues Helliwell, is coming to operate increasingly like avant-garde culture. As relationality gets reified at one end of the scale, it is turned into a funding criterion for art production at the other. This attempt to ascribe to art a ‘social function’ spells doom, argues Helliwell, in step with Adorno, as its defining ‘autonomy’ is undermined.

By way of a coda to the debate, as well as the chapter, Howard Slater throws into relief the self-evidence of critiques of relational aesthetics by contemplating the work of little-known singer/musician Ghédalia Tazartès. The uniform formatting of social relations by social networking sites and the music industry depends on the uniformity of coherent subjects. By contrast, the music of Tazartès, developed in semi-obscurity over 25 years, acts as a ‘taunt to unity’ which outs the musician as an ‘exposed “fake”’. His guttural voice, which moves across chimeras of identity and nationality, articulates the multiplicity of the self and the lie of identity. Such a refusal of identity reminds us of the distance that still exists between avant-gardist rejections of authorial self-hood, and the pseudo-relationality of the culture industry, with its dependence on stable identities, as it battles the crisis of digital abundance.

Composing Ourselves

Radical 70s music theorist Jacques Attali came to London looking to reinvigorate debate around his theory of ‘composition’. Flint Michigan thinks it’s more debatable than ever.

As the author of one of the most provocative works of music theory, one that attempts to rescue music from the throes of its de-politicisation, Jacques Attali’s recent reappearance in London fell a long way short of expectations. Going by the edited transcript of Attali’s ICA talk in Wire magazine No.129, Attali’s ideas, first presented in his 1975 book Noise: The Political Economy of Music, remain undeveloped and lacking in self-criticism. In many ways his ‘political economy of music’ awaits its critique for, as it stands, many of his more radical notions have been undermined by his offers to manage cultural dissent. An offer which has landed him work with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and which is reflected in the ambivalence of statements such as: ‘Organising noises, creating differences in noises, is a way of demonstrating that violence can be transformed into a way of managing violence.’ <1> Does his reappearance on the circuit some 25 years after the book’s publication, the photos that adorn the Wire article, and his failure to acknowledge the intellectual milieu that gave rise to his book (Baudrillard on the ‘political economy of the sign’ and Enzenburger’s Constituents of a Theory of the Media, etc.) not suggest that once again we are in the presence of a Public Intellectual? Is he yet another one touting his ‘discourse-object’ to a public raised on the pacifying format of the seminar? One aspect of his book’s appeal, as with Baudrillard’s work, is his claim to have surpassed the political economy of Marx. Whilst such an endeavour is necessary for getting to grips with an acculturated capital, it is also more often used as a demonstration of intellectual might.

That said, Attali’s key concept, that of ‘composing’, is itself surely a reworking of Marx’s idea, buried in the Grundrisse, of ‘really free working e.g. composition’. This indebtedness to Marx may explain why Attali uses the term ‘composing’ when what he describes has always struck me as lying closer to ‘improvising’: ‘Beyond the rupture of the economic conditions of music, composition is revealed as the demand for the truly different system of organisation, a network within which a different kind of music and different social relations can arise. A music produced by each individual for himself, for pleasure outside meaning, usage and exchange.’ <2>

One of the difficulties with Public Intellectuals such as Attali is that once they have theorised their ‘beyond’, they can’t find the collective subjects to propel the social change that they apparently desire. But whereas Baudrillard, in the early ’70s, urged ‘symbolic transgression’ as a counter to the enforced diversification of the working class, at least Attali has the more concrete notion of the antagonistic musician in mind – an idea of the musician pegged to the movement of economic history and its changing codes. But as the quote above testifies, his notion of ‘composing’ is seriously problematic. What does this ‘individual pleasure’ signify, what ‘code’ does it uphold? At one point in Noise, perhaps lost for words, Attali offers it up as ‘egoistic enjoyment’ and, with that, the dim outline of a collective subject seems to disappear from our view.

So, the radical potential of Attali’s ‘composing’, whose bass-line is the reappropriation of our time and labour from the capitalist process of exchange-value, is negated by what Baudrillard calls the ‘private individual as productive force’ in which it is implicated. For me this explains why Attali has difficulty developing ‘composition’ beyond those individualist dimensions that are of prime importance to the music industry. For ‘pleasure outside meaning’, which abandons the construction of new meaning, simply reaffirms the capitalist paradigm founded on the relation between the individual and pleasure. The exploration of this relation, which marks the subversive impact of improvisation, is also one that reaffirms music as a commodity, a reified relation that submerges the social relations improvising can bring to the fore. So, as a ‘new’ concept of political economy, ‘composition’, as Attali leaves it, becomes readily assimilable to the ‘individualist productive force’ of the music industry. As egoistic enjoyment it can once more act as a sublimator of violence: ‘We can explore these different forms of organisation [of music] much more easily, much more rapidly, than we can explore different ways of organising reality.’ <3>

For ‘composition’ to work critically, as an antagonistic practice, the ‘network’ of which Attali speaks needs to be something more than a simple homologue of the network of political economy already monitored by the music industry. For its social relation to be something more than an exchange of discourse-objects, then maybe, with a nod to Attali, we should make a music without instruments, compose our own social relation and use the resultant music to ‘explore different ways of organising reality’. The critique of Attali’s political economy is a practice of collective subjects.

Flint Michigan

<1> Jacques Attali: ‘Ether Talk’, Wire, No.209, July 2001. Is this not another way of saying that music can be used to manage antagonism?

<2> Jacques Attali: Noise - The Political Economy Of Music (1975), Manchester University Press, 1985, p. 137

<3> Jacques Attali: ‘Ether Talk’, Wire, No.209

Jacques Attali, Noise: the Political Economy of Music // University of Minnesota Press, 1985 // isbn 0816612870

Concentrated Listening

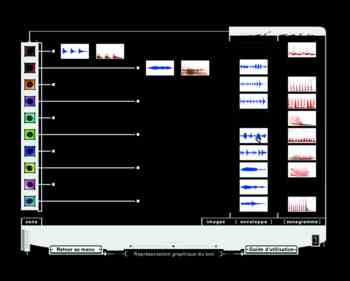

In the second half of this month’s Special, Flint Michigan explores the broad church that is ‘musique concrète’. From maths nerds obsessed with seriality to sonic activists standing around in parks with microphones, the avant-garde has gone to very varied lengths to release music from the ivory tower of composition by letting in ‘real world’ sound. But, argues Michigan, too much ‘concrète’ can be just as restrictive CANONMost of the early histories of electronic music take as their starting point two post-war institutions that pioneered experimental perception by means of music: the Groupe Recherche Musicales (GRM), established in Paris in 1945, and the Cologne-based WDR radio studio. Both institutions were interested in moving away from the timbral restriction of orchestral instrumentation and, to varying degrees, a departure from the reliance upon notation. Perceived as restrictions upon perception, these two parameters had already been subverted by those such as Edgar Varèse with his use of percussive timbres and handwound sirens in Ionisation and, more presciently, in both his wish for sound to be studied scientifically and in his often thwarted plans to make electronic music. Both of these wishes were to some degree realised by GRM and WDR. The former, founded by Pierre Schaeffer, was the home of ‘musique concrète’ – a movement that sought to explore the sonorous qualities of objects, inventorise them and to compose using the resultant ‘found sounds’. The latter, the home of ‘electronische musik’, substituted the pure pitches of electricity for conventional classical instruments. However, if GRM and WDR had succeeded in developing new timbres with which to intensify aural perception, the persistent virtuosity that Varese sought to disassemble returned in WDR’s attempts to perfect the mathematics of serialism, and the compositional accents which, with GRM, came to form the ‘spine of narrative’.

DESIRING PERCEPTIONFrom its early days of being a kind of counter-institution the GRM and musique concrète quickly became a canonical alternative. Schaeffer’s A La Recherche d’une Musique Concrète (1952) carried the sub-text that experimentation with sound could be reduced to a methodology. With the emphasis on studying sound objects and on sonorising narratives, the GRM provided a framework that could cushion the affectivity of sound – sound was harnessed to traditional artistic purposes and not to cultural dynamics that could help to change perception, make perception a conduit of desire. For Schaeffer, the musical object, when separated from its context, was to be used ‘according to its familial relationships and the concordance of its characteristics.’ The ‘concentrated listening’ that Schaeffer had hoped musique concrète would deepen had come to focus exclusively on the object, thus reducing the potentiality of aural perception to sound for sound’s sake. Such restrictions not only served to reify musical practice under the auspices of a research program, but also reinforced the authority of the composer to the detriment of the listener. In this light ‘concentrated listening’ comes to imply a scholarly command rather than a mode of intensified listening that is more fitting to the fusion of desire and perception.

ALMOST NOTHINGWith the wider availability of recording equipment and studio technology the institutional control of sound experimentation passed into less didactic hands. Those interested in the ‘found sounds’ associated with musique concrète came to reject the strict confines of the ‘musical object’ as they began to turn the microphone onto the social world around them, extending the notion of music beyond that of the dominant representation of the musical. In this way musique concrète began to mutate into the field recording epitomised by Luc Ferrari’s Presque Rien No.1. Setting his microphone on the window ledge of a bedroom that overlooked the harbour of a Yugoslavian fishing village, Ferrari proceeded to record the sounds in the early hours of the morning: ‘I recorded those sounds which repeated everyday: the first fishermen passing by... events determined by society.’ The resultant piece, frowned upon by his colleagues at GRM, was in many ways an extension of Cage’s 4’33’’: rather than remaining in the auditorium to demonstrate the loudness of ‘silence’ as Cage had done, Ferrari abandoned the legitimation of the institutional site at the same time as he abandoned his identity as ‘composer’ to become a meta-musician. Presque Rien, in setting the ‘composer’ alongside the listener, immerses both in the miniscule sounds of the social. Rather than maintaining desire and perception as mutually exclusive, rather than have compositional form reify the passage of time, Ferrari offers up the informal and infinitesimal creativity of a ‘situation’. As Gilles Deleuze puts it in Cinema 2: ‘between the reality of the setting and that of the action, it is no longer a motor extension which is established, but rather a dreamlike connection through the intermediary of the liberated sense organs.’

SECOND NATUREWith the work of Chris Watson the field recording came to represent the antithesis of the ‘dreamlike connection.’ Rather than mobilising desiring-perception by means of an undirected attentiveness, Watson’s meticulous recordings of natural sounds not only direct percepetion to pre-existing representations, thus creating a ‘sound realism’, they also take their legitimation from the concept of nature as authentic experience. Such a narrowing of focus for musical practice has the effect of severing desire from perception by drawing desire into registering the authenticity of the perceived rather than inveigling desire to alter perception. In this way the senses are not ‘liberated’ to become ‘theoreticians in their immediate praxis’ (Karl Marx), a dialectic of knowing and feeling, but become adjuncts to an inflation of the represented – an overinvestment in that which is already perceivable. With Ultra-Red’s project Second Nature, based around the struggles of gay groups to maintain the open spaces of Griffiths Park in LA, musique concrète came to be inflected with a political intent. From its opening sounds of outdoor love-making we are witness to desire being an immediate component of the sounds themselves.These extend to the ambiences of the park and suggest that the social field which Ultra-Red are recording and altering is the site for diffuse desire; it is space itself that can be cathected, modified, made conducive to desire. Furthermore, as the title of their project suggests, there is a move away from the naturalistic use of an authentic nature and the positing of a second nature. That the sounds are presented to the listener in microscopically altered form not only sensualises perception, but hints at the ‘subtilised’ perception of new desires and new drives. Such a ‘second nature’ is played out in the way that Ultra-Red do not respect the naturalising authenticity of the ‘field recording’, but instead reveal that the natural is produced. Not only is protest made instinctual and homosexuality returned to nature, but the digital exploration of sound sources, brings a fledgling politics of music to the fore: the binding of aesthetic form, the slavishness of canonical legitimation and the escalation of the represented are outflanked in favour of a pursuit of what it is now possible to perceive and alter. Schaeffer’s ‘concentrated listening’ can thus become the sharing of ‘micro-perception’ between producer and listener which, in its abandonment of notation and familiar timbres, is itself productive of a micropolitics of affective linkage – no longer is a divide maintained between composer and listener but both become metamusicians; listeners as operators.

Dissimulations

The Illusion of Interactivity

The Interactive Story

...myth, legend, fable, tale, novella, epic, history, tragedy, drama, comedy, mime, painting, stained glass windows, cinema, comics, news items, conversation. 1

The form of the story permeates every aspect of our cultural life. History, politics, memories, even subjectivity, our sense of identity, are all representations in narrative form, signifiers chained together in temporal, spatial, and causal sequence. Narrative appears to be as universal and as old as language itself, and enjoys with language the status of a defining characteristic of humanity and its culture. A people without stories seems as absurd an idea as a people without language, (a people with language but no stories even stranger, for what is language for if not to tell stories?)

Over the past few years there has been a tremendous investment in the idea of digital media, the use of computers as the site of culture rather than just tools for business or science. This is partly due to the drive on the part of manufacturers to create new markets as price/performance ratios in digital technology improve, but, at the same time, there is a desire at work here, a fantasy which exceeds its technical and economic conditions. Implicit in the notion of digital media is the belief (read desire) that digital computers and digital communications will provide a unified site for 1st world culture in the near future and that this new medium will offer distinct advances over existing media, above all by offering its audience interactivity.

Interactivity refers to the possibility of an audience actively participating in the control of an artwork or representation. For the purposes of this discussion, interactivity means the ability to intervene in a meaningful way within the representation itself, not to read it differently but to "(re)make" it differently. In its most fully realised form, that of the simulation, interactivity allows narrative situations to be described in potentia and then set into motion – a process whereby model building supersedes storytelling, and the what-if engine replaces narrative sequence.

There are those who see the replacement or narrative form of interactive simulation as political progress. Many who in the 60s and 70s rejected the blandishments of mainstream narrative, the elision of its own means of production and the naturalisation of passive spectatorship, discern in interactive media an opportunity to go beyond the impasse of avant garde structural materialist film practice. Similarly, in the rhetoric of neoliberal political thought interactivity can be figured as a form of freedom, a liberation from the tyranny of authorship and the servile passivity of reading.

This discussion is an attempt to speculate on the collision between a dominant cultural form – narrative, and the technology of interactivity. I will argue that there is a central contradiction within the idea of interactive narrative – that narrative form is fundamentally linear and non-interactive. The interactive story implies a form within which the position and authority of the narrator is dispersed among the readers, in which spectator-ship and temporality are displaced, and in which the idea of cinema, or of literature, merges with that of the game, or of sport. Can an interactive construct, or a simulation, successfully adopt a narrative form?

Forking Paths and Synthetic Spaces

In his short story Garden of Forking Paths2 Borges imagines a novel in which the path of the story splits, where all things are conceivable, and all things take place. The author of this story within a story is judged insane and commits suicide, and Borges' narrator is arrested and condemned to death – thus the fate of the narrator and of the author in the interactive era is prefigured. It is not hard to see how the task of writing interactively might drive an author to insanity and suicide. To write not simply an account of what happened but a whole series of 'what-ifs' increases both the volume and .complexity of an author's task exponentially. In addition the situation is one in which the ability to develop the action in a particular direction is no longer the unique prerogative of an omnipotent author as his/her role is partly usurped by the reader.

How much interactivity does it take to make an interactive story? We don't know because we don't know what an interactive story is like, nor what it is for (more on this in a moment). It is true that the number and complexity of forking paths could be increased until the reader experiences a large degree of freedom and control within the text. The limits of this freedom are achieved within a constructed model that dispenses with the network of lines altogether, replacing it with a fictional space within which readers can turn left or right, look up or look down, open a door, enter a room, at any time they choose - a spatio-temporal simulation which can generate a travelling point of view in real time, more commonly known as virtual reality or VR. In the VR model, although the reader/spectator enjoys seamless temporal and spatial liberty, the tradeoff between interactivity and richness of content holds true. VR to date has barely been able to dress the set, let alone cry 'action', or murmur 'once upon a time'. And there is another simpler and deeper problem. This is the question of ontology. The change from a linear model to a multi-linear or spatio-temporal (VR) model involves moving from one kind of representation – and one form of spectatorship – to another.

A Lonely Impulse of Delight

As he settled into the snug cockpit he tried not to think about the obvious thing. Ahead of him, through the windscreen, he could see a long low hill. It was further away than it appeared to be, and much bigger. Yellow through the blue haze, the hill squatted on the plain, low and indolent and massive. He wanted to be over that hill and look beyond.

Before him stretched the grey runway, on the left a yellow haystack, on the right a white airfield building. All around him was the blue aeroplane.

Afficionados of the Hellcats flight simulator will recognise the landscape – an American airstrip on one of the Solomon Islands in the Pacific Ocean. The time is WW2. This is the prologue to an account of an experience of my own, flying a Hellcat on a mission against the Japanese Navy.

Hellcats is effectively a screen and mouse based virtual reality system – 2 nd person VR – offering non-linear adventure stories. The reader – or should it be participant, or player – is free to move in any direction, at all times, as long as he or she never gets out of the plane. This cuts down the scope of the story significantly – it's like Top Gun with everything but the flight scenes cut out.

As a representation of the experience of Americans during WW2 in the Pacific, Hellcats can be compared to South Pacific or From Here to Eternity. Yet despite the similarities of place and time, Hellcats is a very different kind of representation. Hellcats represents one specific aspect of the experience of the war in the Pacific, but it is the experience of the pilot. More precisely, it is the experience of the pilot insofar as he or she is an extension of the machine. Certain key attributes of narrative form are missing3 . Narrative closure has to be fought for – if you crash your plane while taking off the 'story' is short, insignificant and unsatisfying. It is up to the spectator to ensure that the action comes to a satisfying and meaningful end – closure is contingent on the moment of 'reading'. Temporal and spatial coherence are more or less complete, but strictly limited to the skies above the Solomon Islands. There is no specific enigma to be resolved but a different kind of teleological imperative, that of a participant in a violent struggle. If we consider what Barthes has called the symbolic code, that code which accounts for the formal relationships created between terms within a text – the figurative patterning of antithesis, graduation, repetition etc, we find it absent in Hellcats. The simulator does not signify in this way. Neither do we find much in the way of a referential or gnomic code, the code of shared cultural knowledge about the world, nor the rich and diffuse code of connotations designated by Barthes as the code of semen. The complex interplay of signs, Barthes' 'weaving of the voices' across different registers, the 'multivalence of the text' is lost, replaced with a wide band of sensory information referring to specific and schematic aspects of a situation – the proairetics of flight, the hermeneutics of battle.4

However, although complex narrative codes are not hard-wired into the simulation, they are not therefore altogether absent from it. The simulation is re-invested with narrative sense via the subjectivity of the participant – a personal, transient, and contingent narrative unlegitimated by the external figure of the author.

Time

I saw the movie last week. I want what happened in the movie last week to happen in the movie this week too, otherwise what is life all about?5

A key distinction to be made between an interactive representation, like Hellcats, and narrative representations like those of the cinema and literature, lies in the way time is represented. Narrative refers to the past. Its temporal referent is once upon a time, The simulator on the other hand operates in the present. If in a narrative an event happened, in an interactive narrative, whether multi-linear or spatio-temporal, an event is happening, its time is now. This temporal shift has important consequences.

A linear narrative exercises a textual authority which is dispersed by interactivity. In a linear narrative, the reader submits to the prior authority of the text. Only the author has the power to make decisions about the story-line or point of view, and the invention of narrative sequence is his or her sole prerogative. The text is certain of itself. Moreover this certainty has a legitimising function. Hayden White writes:

`We cannot but be struck by the frequency with which narrativity, whether of the fictional or the factual sort, presupposes the existence of a legal system against or on behalf of which the typical agents of a narrative account militate. And this raises the suspicion that narrative in general, from the folktale to the novel, from the "annals" to the fully realised history, has to do with the topics of law, legality, legitimacy or more generally "authority””.6

Now this authority is expressed, and legitimacy conferred, at the moment of closure. By recounting what happened an author is also closing off those things which didn't happen. A character picks up the phone rather than letting it ring, someone walks down the street and turns left instead of right. Closure in this sense is dispersed throughout the narrative. The events unfold as a pattern which progressively resolves itself into an image, each event integrating those which precede it into progressively higher levels of narrative sense. This process continues until the final closure at the end of the narrative, at which point the meaning of the story is revealed at last, and is revealed to have been immanent in all the events all along. Closure can be considered as a function of time, or more precisely of the way in which time is represented, whether as past and complete or present and ongoing.7

Aspect

In his standard work on aspect8 the linguist Bernard Comrie distinguishes two forms of time reference in language – aspect and tense. Tense 'relates the time of the situation ... to some other time, usually to the moment of speaking', whereas aspects are 'different ways of viewing the internal temporal constituency of a situation'. Where tense distinguishes between situations taking place in the past, present or future, aspect draws a distinction between the perfective; a situation viewed from the 'outside' as completed, and the imperfective; a situation viewed from the 'inside' as ongoing. The shift from narrative representation to interactive representation entails an aspectual shift like that from perfective to imperfective, from outside to inside the time of the situation being described.

Thus aspect distinguishes between different ways of positioning the audience with respect to a situation. The perfective and imperfective aspect, and by analogy linear narrative and interactive simulations, correspond to two fundamentally different modes of spectatorship.

An interactive simulation appears to designate the conditions for events rather than the events themselves. The interactive simulation sketches a web of possibilities and constitutes a system for producing story events in time – a story engine rather than a story.

It is in their respective modes of closure that we can locate the apparent disjuncture between the nature of interactivity and that of narrative. Thus, the moment the reader intervenes to change the story, perfective becomes imperfective, story time becomes real time, an account becomes an experience, the spectator or reader becomes a participant or player, and the narrative begins to resemble a game.

Games and Stories

In AN EXAMINATION OF THE WORKS OF HERBERT QUAIN9, Borges invents an English multi-linear novelist of the 1930s. Less often referred to than GARDEN OF FORKING PATHS,

this short story is no less remarkable for its dystopian vision of a banal and meretricious interactive literature – what Borges terms the 'regressive, ramified novel'. Borges prefigures the transformation of reading into playing when he makes Herbert Quain say of his second novel, `April March',

`I lay claim in this novel... to the essential features of all games: symmetry, arbitrary rules, tedium. Indeed, 'Quain was in the habit of arguing that readers were an already extinct species. "Every European," he reasoned "is a writer, potentially or in fact."

Does something which is interactive have to be like a game? And if so, does a game have to be as uninteresting as Borges suggests?

Max Whitby 10 argues that the term interactive narrative is an oxymoron – and believes that an interactive narrative can never be as satisfying as a traditional linear story. Interactivity gets in the way.

`Every successful form of communication involves protagonists, a set of conflicts and experiences, and at the end some sort of resolution so the thing has a satisfying shape. Interaction largely destroys all that. By giving the audience control over the raw material you give them precisely what they don't want. They don't want a load of bricks, they want a finished construction, a built house.

One form of Interactive multi-media that does make sense is that of the game.. Computer games are as spellbinding and absorbing as a good movie. However, what is going on in people's heads in a game is very different from what is going on with a play or a novel. I don't want to say that one is better than the other, but you can obviously do things in films, theatre or the novel that you can't do in a game, and vice versa. Most of what is generally regarded as being interesting belongs to the world of cinema and theatre and most of what we could regard as simply diverting or just a pastime belongs to the form of the game."

Value

So far I have argued for a distinction between narrative and interactivity, or stories and games, which is based on the different way each represents time, leading on to differing modes of spectator-ship. However, as Max Whitby points out, games and stories also have very different cultural values attached to them. The game is frivolous whereas narrative is serious.

There is a general assumption here that narrative representation - literature, history, cinema and so on, has a deep and lasting significance which the game lacks. In the end Shakespeare or Proust or Pasolini seem to have more to offer than a game of football or Sonic. The game is outside of history, unworthy of serious remembrance. At the M.I.T. multimedia conference in Dublin in 1993 a speaker bemoaned the fact that his son spent too much time playing computer games and not enough time reading books. Thinking of my own child, I found myself nodding in agreement. Yet when a woman asked from the floor why reading a book was better than playing a computer game, he couldn't explain his assumption and neither could I. Two other speakers gave a fascinating account of an elastic movie. This was a multi-screen installation constructed as part of a student workshop at M.I.T. which the spectator moved through and interacted with. The speakers called it an interactive media environment, an installation, a transformational space, fine art circumlocutions for the obvious term game which they managed to avoid entirely throughout their paper. Then they showed a video of their undergraduate students discussing the design of the project and the word game cropped up over and over again. Finally, throughout the whole two day conference on interactivity, discussion of console and TV computer games was almost entirely absent, in spite of the astounding commercial success of Nintendo and Sega in the youth market, in spite of CD-i, in spite of 3D0...

A Literary You-topia

If the repressed reading of interactivity is that of the game, the preferred readings are interactivity as liberation, and interactivity as Post-Modernism come true.

In S/Z Barthes describes two types of writing, readerly writing and writerly writing. What happens if we take the notion of the writerly at face value, innocently? What if we read excessively, irresponsibly, futuristically.

"The goal of literary work (of literature as work) is to make the reader no longer a consumer, but a producer of the text... The writerly text is a perpetual present, upon which no consequent language (which would inevitably make it past) can be superimposed; the writerly text is ourselves writing...

In this ideal text, the networks are many and interact, without any of them being able to surpass the rest; this text is a galaxy of signifiers, not a structure of signifieds; it has no beginning; it is reversible; we gain access to it by several entrances, none of which can be authoritatively declared to be the main one; the codes it mobilizes extend as far as the eye can see ...' 11

In this excessive reading the writerly becomes a fantasy of the multi-linear text, Barthes a kind of Nostradumus of literary theory, writerly writing the uncanny prophecy of an interactive literature come to pass. Indeed, a number of commentators have noted the way in which post-structuralist writing seems to anticipate the non-linearity of new technology. In

HYPERTEXT – THE CONVERGENCE OF CONTEMPORARY CRITICAL THEORY AND TECHNOLOGY,

George P. Landow suggests that the literary theories of structuralist and post-structuralist thinkers (especially Barthes and Derrida) find their embodiment in interactive hypertextual forms made possible by new technology. Hypertextual and non-linear structures promise Barthes' writerly text, never far from the possibility of rewriting, multivocal, decentred, without boundaries, a text which can break free from the chains of closure, a text whose instability lies not in our post-modern apprehension of it but in its very condition of being. Hypertext for Landow is post-structuralism made flesh, transubstantiated – Foucault's death of the Author a corpse and a smoking gun, Derridean débordement actualized as hypertextual annotation... 12

The problem with this kind of literal and utopian mapping of post-structuralist theory onto new technology is that it fails to acknowledge its own excessiveness. To literally and deterministically locate a set of complex, heterogeneous and ambiguous ideas about the social processes of reading within a specific technology seems to be missing the point. One might as well argue that the telephone system is post-structuralist. It is ironic that a set of theories which stress plurality and indeterminacy should be employed in the service of a reductive equivalence between very different types of object.

Instrumental stories

`Science has always been in conflict with narratives' 13

We have seen how a putative theory of interactivity might oscillate between the preferred register of the post-modern (serious, plural, decentred and legitimated by the academy) and the frivolous register of the game (playful, ephemeral, banal and without value). A further approach is suggested in 'The Postmodern Condition' in which Lyotard outlines an opposition between narrative knowledge (convivial, traditional) and instrumental knowledge (cybernetic, scientific). The game can be considered as a cybernetic construct (a goal directed system of control and feedback) and as such, placed on the side of the instrumental, whereas narrative knowledge, argues Lyotard, is an older form – 'narration is the quintessential form of customary knowledge...' and 'what is transmitted through narrative is the pragmatic which establishes the social bond'. Legitimation and authority are immanent to narrative form and are established within and through the act of narration itself (see Hayden White quote above).

By contrast authority and legitimation are extrinsic to the form of instrumental knowledge. In scientific discourse legitimation must be fought for. Moreover, instrumental knowledge according to Lyotard is set apart from the language games that constitute the social bond. The analogous oppositions may be summed up thus:

INSTRUMENTAL

NARRATIVE

KNOWLEDGE

KNOWLEDGE

science

history

simulation

narrative

game

story

uncertain

legitimate

synchronic

diachronic

These oppositions sketch out the structural differences between two different kinds of representation, and two modes of spectatorship. It seems that the truth-effects of stories and games are very different. The question of legitimacy and certainty is central – the simulation remains a model which does not have the ability to auto-legitimate itself in the way an account does. Structured as it is around a core of what-if statements, the truth of a simulation or game can never be more than hypothetical.14

Conclusion

There are two potential endings for a discussion like this, either optimistic or pessimistic. Neither is sustainable. The `interactivity is post modern' school of thought sees interactive representation as a liberation from the repressive authority of traditional narrative form. There are echoes here from the avant-garde and anti-narrative movements in cinema and writing which have their source in the utopian ferment of the 60s. Yet the consequences of the opening up of closure -that interactivity will be `commonplace, unlaborious, shallow, un-literary, heterodox'15 are more difficult to accept.

Others see the simulation as promising post-symbolic representation, bypassing the patriarchal distortions of perspective and the controlling point of view. An interactive simulation, according to this argument, offers not the representation of objects but the representation of relations between objects within which the participant can select their own point of view. However, in characterising this as a shift from coded representation to experiential post-representation what is glossed over is the coding and mediation involved in constructing the simulation in the first place. Sim City, the town planning simulation game, is just as much a cocktail of opinion, received wisdom and political ideology as any other doctrine of urban decay and renewal – it simply hides its politics more effectively.

Is this the end of the road for narrative, grand or otherwise? Are we to become a people without stories? Once again the linguistic category of aspect provides a useful analogy here. We have seen how the shift from narrative to the interactivity involves a shift from perfective to imperfective, from outside to inside the time of the events being described. Thus, narrative representation and interactive representation might be 'different ways of viewing the internal temporal constituency of a situation' as well as different forms of spectatorship.16 As interactivity increases, so the spectator is thrown inside the representation to become a player.

At the heart of the interactive representation narrative reinstates itself through the subject narrativising the experience making sense from (simulated) events. If narrative is a technique for producing significance out of being, order out of contingency, then simulation can be seen as its inversion, a technique for producing being out of significance, of generating simulation of contingency from first principles. Rather than a people without stories, interactivity offers the promise of people within stories, and rather than the end of narrative, an explosion of narrative within the simulator.

Like any other form of representation interactivity is an illusion. It puts itself in the place of something that isn't there What then might be the absent referent of interactivity? According to both neo liberals and techno-utopians interactivity promises the spectator freedom and choice. It is precisely the absence of such freedom and choice that interactivity would appear to conceal.

1 Roland Barthes, 'The Structural Analysis o Narrative' Image, Music, Text (London, Fontana 1977)

2 Jorge Luis Borges, 'The Garden of Forking Paths' Fictions, (London, John Calder, 1965)pp. 8 1-92

3 Pam Cook (ed) The Cinema Book (London: British Film Institute, 1987) p.212

In the Cinema Book, Annette Kuhn gives this account of the formal attributes of classic cinematic narrative:

*Linearity of cause and effect within an overall trajectory of enigma-resolution

*A high degree of narrative closure.

*A fictional world governed by spatial and temporal verisimilitude.

*Centrality of the narrative agency of psychologically-rounded characters.

4 Barthes, S/Z, (Oxford, Blackwell, 1990)

In S/Z, Barthes outlines 5 codes of narrative. These are used to submit a short story by Balzac - Sarrasine – to an extremely close textual analysis. Briefly the 5 codes are:

* The code of Semes – broad connotations within the text – femininity, age, etc...

* The Symbolic code – the code which structure the text in figurative patterns – antithesis, graduation, repetition etc. It is difficult to imagine this code within a non-linear, interactive structure the pattern imposed by the author would be lost in the meanderings of the reader.

* The Cultural code – shared knowledge, common sense. See note on Hellcats above.

* Hermeneutic code – 'the various (formal) terms by which an enigma can be distinguished, suggested, formulated, held in suspense and finally disclosed.' An interactive story might be organised principally in terms of the hermeneutic code, a cluster of clues surrounding a mystery could be organised logically yet non-sequentially. The hermeneutic code is goal-oriented, as are most games.

* Proairetic code – the code of the actions, the code of the sequence. This code presents particular problems for non-linear interactive structures A change in one part of the sequence will have the potential to change every subsequent action The proairetic code embodies a relentless logic,

if X is killed in scene 4 then X cannot be alive in scene 5.To an extent then, the proairetic code embodies something of the Cultural codes, the code of knowledge. The proairetic code is the code of knowledge about time, and it is the certainties of this knowledge which interactivity appears to throw into question. There is a parallel between the interactive narrative and the electronic spreadsheet. The linear narrative is to the interactive narrative what the ledger is to the spreadsheet. Both inter active narrative and spreadsheet are 'what if?' engines. Both create the space for multiple parallel time. The best illustration of the problem o the proairetic code in interactive narrative is given by changing one of the numbers in a spreadsheet doing a recalculate, and watching the changes multiply and ripple across the whole sheet.

5 Woman outside the cinema in 'The Purple Rose of Cairo' dir. W Allen

6 Hayden White, 'The Value of Narrativity in the Representation of Reality' On Narrative, (Chicago Chicago University Press, 1981) pp 1 - 23

7 Richon & Berger (ed) 'Fire and Ice' Other Than Itself (Manchester, Cornerhouse Publications, 1990: See Peter Wollen's discussion of the linguistic category of aspect and its effect on spectatorship in ' and the categories of perfective and imperfective in Bernard Comrie's standard work – Aspect.

8 Bernard Comrie, Aspect, (Cambridge, CUP 1976)

9 Jorge Luis Borges, 'An Examination of the Work of Herbert Quain', Fictions, (London, John Calder 1965)pp. 8 1-92

10 Max Whitby heads the Multimedia Corporation, an offshoot of the BBC which produces interactive titles in London.

1l Barthes, S/Z, (Oxford, Blackwell, 1990) pp 4-5

12 'contemporary theory proposes and hypertext disposes; or, to be less theologically aphoristic hypertext embodies many of the ideas and attitudes proposed by Barthes, Derrida and Foucault.' Landow Hypertext, (Baltimore, Johns Hopkins, University Press 1992) p73

13 Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition, (Manchester Manchester University Press, 1986) p xxiii

14 For example, my 5 year old child enjoys crashing the aeroplane when he flies the simulator – it doesn't hurt him to crash the plane. However wheT watching a television documentary about early USAF jet planes, which showed a plane cartwheeling and exploding in a fireball, he was upset because he felt he had seen someone die. The simulated crash and the account of a crash had for him a very different status.

15 Jorge Luis Borges, 'An Examination of the Work of Herbert Quain', Fictions, (London, John Calder 1965)

16 Holt's defintition of aspect, quoted by Bernar( Comrie, Aspect, (Cambridge, CUP 1976) p 3.

Dissimulations is also being published in the Sprint edition of 'Millenium' in New York.

Free Improvisation Actuality

In the wake of the Napster debacle and the recording industry’s recapture of the main means of music’s commodification – the recording – Ben Watson considers Free Improvisation, a music ‘groupuscule’ and attitude which bypasses the music ownership wars, unpredictably

Conventional thinking contrasts classical music to pop, assigning the technologies of score and recording to different epochs. Free Improvisation doesn’t credit the significance of such ‘progress’: on the contrary, classical and pop are viewed as symptoms of an identical malaise. For Derek Bailey and Lol Coxhill and the hundred-odd international musicians who play Free Improvisation in public, recording is simply the technical apotheosis of the score. Following on from the radical critiques of classicism made by both Free Jazz and the ‘indeterminate’ compositions of the 60s, Free Improvisation focuses on a time-based art’s most basic virtue: a cultivation of unpredictability as an end in itself. On the way, Free Improvisation is also an elegant answer to the accusations of recuperation and commodity-fetishism which Situationists, Art Strikers and Neoists hurl at visual artists. Here is an uncommodifiable art-happening that leaves no saleable residue, a poetry of modernist form that truly melts into air.

In 1919, Kurt Schwitters declared in Der Sturm that “a perambulator wheel, wire-netting, string and cotton-wool are factors having equal rights with paint. The artist creates through the choice, distribution and metamorphosis of the materials”. Free Improvisation is aural Dada: any sound source – from traditional instruments played in outrageous ways to crisp packets, Pokémon watches or G3 PowerBooks – is permitted. Sampling and digital editing are ubiquitous, but subject to the judgement of the ultimate receiver: the distinctly analogue interface of airwaves and the human ear. Free Improvisation, one of the few areas of cultural activity that adheres to dada principles, comprises one of the most tenacious and vehement groupuscules in today’s fractured music scene. Although Impro-visation is currently enjoying an Indian summer – Sonic Youth are proselytisers, Tortoise are into it, Blast/Disobey puts its veterans in the lime light – it has weathered Bop, Prog, Fusion, Glam, Punk, New Romanticism, the Jazz Revival, Minimalism, Authentic, Rave, Lo-Fi, the New Complexity and Electronica without losing an (indeterminate) beat. It is fierce, angular, abstract. The timing is super tight, closer to stand-up comedy than to the smudge and fuzz of Post-rock or Ambient. If you can’t play, forget it. Its controversies, schisms and exclusions resemble those of revolutionary politics. Claims to have “broken out of the Improv ghetto” by including such no-nos as tonality, regular rhythm or a hummable melody surface at regular intervals. But, far from accessing the energies of pop or funk, these invariably signal a failure of nerve, a lessening of tension, a lapse into feeble ingratiation.

It’s not always great. Reputations burgeon, musicians coast. A recent complaint – voiced by Bailey, and also by bassist Simon Fell – is that you can predict the music on most Improv CDs by simply checking the names on the box. Musicians develop a personal ‘sound’, and people pay to hear it: what is deemed evidence of ‘genius’ is actually the reassurance of the already-known. So the malign influence of the star system impacts on even these refusenik domains. However, there’s probably no other scene where musicians and listeners are more critical of these and other failings. Free Improvisation: music for those who prefer the chill of actuality to the reliability of the concept.

Ben Watson

Clubs:All Angels T: (0)20 8348 9595 // Cenophelle T: (0)1932 571323 // Flim-Flam T: (0)20 8809 6891 // Free Radicals T: (0)20 7263 7265 // Klinker W: [http://www.theklinker.freeserve.co.uk]Shop:Sound 323, 323 Archway Road, London N6 5AA. E:<sound323@aol.com>Radio:InfrequentPrint:Derek Bailey, Improvisation: Its Nature and Practice in Music (Da Capo) Jeff Nuttall, The Bald Soprano: A Portrait of Lol Coxhill (Tak Tak Tak) and Ben Watson, Derek Bailey & the Story of Free Improvisation (Quartet, forthcoming)

Free as the Air

Eddie Prévost, percussionist and pioneer of improvised music – notably as co-founder of the seminal ’60s band, AMM – takes aim at the increasingly ubiquitous practice of sampling

I’m sitting there on stage with my drum kit, barrel drum, cymbals, gong and bits and pieces. Beating and bowing. I’m listening to the other musicians. Then I hear a sound that is familiar yet wrong. I’ve heard it before but it’s out of phase, out of joint, displaced, dislocated. It’s me but I’m not doing it. The phantom sampler has struck.

The conventional wisdom is that it is flattering to be copied. There was a time when copying was so difficult that one admired anyone who got near to the original. Now anyone – with the right gear – can do it and you can hardly tell the difference. This is because there is no difference! The time frame can be so condensed (almost real time) that the copy can come out almost before the originator is aware of what they have done in the first place. The train seems to reach its destination before the engine has left the station!

All this can be slightly unnerving. A new relationship has developed in which there has been no negotiated social contract. I’m not so worried about any financial drop out by unlicensed use of my intellectual property. I can’t make much money out of the sounds in the first place, so it seems churlish to object to anybody else trying. No. What bugs me is ‘I’ am being selectively cannibalised, and, it’s behind my back (if you know what I mean?). Somehow my sounds, once they are made, are considered to be no longer part of me. They go out of my control. They are deemed lost. Being lost means that they can be ‘found’ and used without a ‘by your leave.’ Recording a sound somehow confers or transfers its property status.

There was a good deal of mischievous humour attached to ‘plunder phonics.’ It took – mostly from commercially popular sources – existing recorded material: treating and incorporating it in a subversive way into another art medium. It poked fun at the pop artist who was being plundered. They were placed in a position of some cultural discomfort.

But are sounds made ‘free’ by releasing them into the environment? Can a sampler claim to have ‘found’ this source material. Claiming that something has been found is no proof that it was lost or that its original owner has no continuing rights or responsibility as to what happens to it thereafter. So far samplers are assuming rights in the absence of any counter claim. It feels like being mugged. It has been argued that such activity is justified as a response to the expropriation and mass exploitation by powerful capitalists. Unfortunately, a by-product of this action is to unconsciously recommend that it serves as a model for our relations with everyone. All people and their products become valid sources for unregulated and abusing expropriation.

Let me run this past you. I reckon that if someone, without my permission, can use my sounds then they give me license to intercept their sonic output. Is there not an implicit contract here? A mutuality? If anyone takes unasked then surely the taker should be prepared for some kind of natural reciprocity. Yet can you imagine what would happen if I moved the speakers or turned the volume down on a fellow musician who was carrying out sampling? All hell would be let loose. I would be infringing their rights of ‘free’ expression.

Eddie Prévost <prevost AT matchless.sonnet.co.uk>

Guttural Cultural

During a career spent in virtual obscurity, Ghedalia Tazartès whittled away at the coherence of musical identity, moving through modes of articulation as a guttural nomad. Now a box-set collates his multiple voices. Howard Slater raps uvular, in prose and notation

A box set that gathers together and reissues the three previous Ghedalia Tazartès releases on Alga Marghen, throwing in the usual bonus tracks, is par for the course in the music industry's ordinary sale of things. But that’s where the similarities end. The form of the product may be pretty acceptable and collector-inducingly obsessive, but what’s contained in it openly and, it could be chanced, unknowingly, defies categorisation. If you’ve not come across Tazartès before you’ll be in a majority, but, getting outside the mirror-scene a bit, your ears will become noisily whispered into by a minor voice. A voice so minor, yet layered, that it operates at the unpredictable level of molecular switchpoints; switchpoints of alterity without the border controls of introjected censorship. It’s a voice that’s been left alone enough (his first LP was released in 1979) to become a population of multiples, of ‘vitality affects’, but it’s also a voice that wields and is embedded in a variety of machines.[1] From grimy electronic loops to mock opera, from world-music to found sounds, from guttural sonorous inarticulacy to the lyrical flushes of Mallarmé and Daumal, from an improvisatory nonchalance to a textured choreographic plan, the ‘music’ that opens out here has taken twenty-five years to gain even this small level of exposure (Alga Marghen is hardly a label that people rush to Myspace to research!).

In eluding the taxonomy tax (a tax I feel I’ve tried to levy in even attempting to describe the music) Tazartès has been effectively seceding from all but a local popularity. At one level his other recent CD releases have been issued by very small-run French labels such as Demosaurus, Jardin Au Fou and Gazul, but the localness of Tazartès is there in the intimacy of risk across all his records; a kind of invite to share in all the dislocation of impromptu passion. We are made congruent in listening to Tazartès as he actively works with the material of his ‘self’, with personified emotions made dissemblingly sonorous, putting us in mind of Nietzsche’s shocking challenge to the identitarians: 'finally you are no more than an imitation of an actor'.[2] The centre, the locus has been removed, diffused, and subjected to a continual deferral of its stultifying and inhibiting taunt to unity. It is this focus for self-regard that, as he whines and whimpers like an exposed ‘fake’ or one at the limit-point of verbal expression, Tazartès implicitly maintains is the fiction. As controversial philosopher André Glucksman states on the sleeve notes to Diasporas, 'Ghedalia Tazartès is a nomad'. A much overused term should not detract from its accuracy when applied to this music: Tazartès not only wanders, sui generis, through the many musical categories and delimited locales that instill a self-affirming unity, he is lovingly in internal exile. Like a latterday Rimbaud he is an alchemist of the very local affects that he brings into voice and thereby discovers; affects that are both audibly inspired and reach-out to a taped militant chant, a city square ambience, a tango refrain, a broken organ, a synthesized rhythm, his daughter gurgling or a massified cathedral bell.

This localness, this locale of a porous psyche in an admixtured place, is further contradicted with the overall sense of transports and movement we get when listening to these records. On Diasporas the overall thematic seems to be the aping of a North African way of singing which, these days, leads to all sorts of musings about cultural pillage rather than cultural inter-penetration. As there’s very little biographical information on Tazartès we can hardly know for sure he’s not of North African descent nor whether or not he once worked at General Motors. But, this seems to be a decoy kind of response to a bogus question that leads back to the essentialisms and non-becomings of a cultural homogeneity, to a respecting of the boundaries and financially beneficial closed markets that are enforced by cultural commentators and treaty-makers alike. Tangiers is now in Paris via Istanbul. On Diasporas, a track with the Ubuesque title of 'La Vie et la Mort Legendaires du Spermatozoide de Humuch Lardy' (The life and legendary death of the sperm of Humuch Lardy), we hear Tazartès singing to an accordion-like instrument underpinned by a steady beat on a djembe. Yet Tazartès changes his vocal style continually throughout the three minutes of this track from vaguely islamic to vaguely jewish to vaguely sioux indian to vaguely feminine to explicitly cutting into the ‘melody’ by ha-hack-laughing like a temporarily mad man. The temptation would be to say, ‘here in Tazartès, we have someone articulating what it is to be a species-being’, or, ‘here, in Tazartès, we have the first pre-articulation (outside sci-fi) of the push to form a world government headed by conformed intellectuals’. Both responses would be undermined by the self-effacingness of this very idiosyncratic, self-exposed and disorientating ‘music’; a ‘music’ that the Musearecords website [http://www.musearecords.com/] tells us began when Tazartès ‘started to sing, at 12 years old, in the Bois de Vincennes, just for himself, after his grandmother died’. Grief is unlocalisable as is the plurality of worlds that Tazartès presents; a ‘redistribution of the sensible’ (to adapt Rancière’s phrase).[3]

Whether Tazartès assimilates or disseminates, comes together or openly unfolds, is not a choice we, as listeners, have to make. He does all these things. He is not national, but differentiated and relational. Layering the bass timbre of his own voice into a chanted drone, adding a synthesized note, overdubbing a murmured refrain, goading himself into declamations of parodic or justifiable anger, he assembles sketches that have the impact of concertos. He multiplies himself into a contradiction of unedited tensions, colliding the disparate times of feeling with a minimum of respect paid to ‘song structure’ that makes Glucksman’s description of him as 'an orchestra and pop group all in one person' entirely fitting. On 'Merci Stephane', Tazartès recites, body and soul, a poem by Mallarmé (in French) as a disco loop, complete with Chic-style rhythm guitar, slowly rises to the foreground of the track. We don’t get the message as such, we get, more provocatively, the enigma. Akin at times to the later recordings of Luc Ferrari, who also did not shy away from the use of popular forms, Tazartès’ similar use and magnification of the incidental, when coupled to his overdubs, summons up, as with Ferrari, a very real sense of ‘temporal thickness’: not just our experiencing of music but our experiencing in general can be polyphonic and polytemporal. The key to this ‘thickness’ may lie not just in the way Tazartès can have us seemingly at the origins of language with a totemic incantation being accompanied by a buzzing cellular network sound, but in the way that this ‘thickness’ is intimately relayed across these twenty-odd year old recordings by timbre, dirty timbre.

It’s timbre that’s outernational. Timbre is the grain, the rasp, the fricative, the aural visceralisation of an unfurling emotion, a ‘vitality affect’. It is fitting and fits with an attempted expression, not a well rehearsed one. When it’s alloyed to the incidental and the impromptu (for all Tazartès’ tracks may be layered but each layer comes across as being put down with no second takes) it amounts to a pre-articulation, an indication of a struggle, a none-too easily won means of expression, a means without precedent but not individual, singular instead, a group’s pre-articulation, the group of the multiple self dissolving the boundaries of the overly identified who want to win you over for lessness. So, in some ways we are talking, thanks to Tazartès, of something more vital and communicative than language; for across these tracks there are words (in French) many will not be able to understand. But this does not detract from our ‘understanding’. Quite the opposite; it tempers our understanding with enigma and leads us to put trust in the ‘unspoken’ meaning of the timbre, be it of the voice or the variegated musical backing, applying to it a sincerity of intent and giving to us the image of an ‘unthought known’[4], of something happening to the side of consciousness in a duct, a quiver. This is in stark contrast to a more recent and much acclaimed album by Scott Walker. Presented as a similarly heady mix of voice and unfamiliar musical backing, The Drift comes across as firmly implanted in the majoritorian culture of High Art Darke; a monotonal operatics with tracks as long as the last days of drum and bass. Here we can fully ‘understand’ the lyrics – they are an hermetic appeal to englishness graduates. Maybe it’ll be Ghedalia’s gypsy-band with their partially unwilled responses that’ll be visible on the horizon at the next Meltdown.

Audio Clip – Une Éclipse Totale de Soleil

Distorted drum box.

Bass blurs in a pumped semitune

Birds.

A child unspeaks.

Sings as if alone, straining to reach the high notes.

Another voice yodels to a repeated syllable.

Its throat becomes a cavernous auditorium.

Other voices rise, desperate and yearning.

Voices of ecstatic protest.

Voices of an affective class.

Notes from an oud or a one stringed violin enter.

Still the repeated syllable.

Is this the desert, a drawing room, an agora?

Some inviting schizo demos?

It’s not a studio.

But the window is open:

birds again.

Pots and pans are struck nonchalantly as if trying to

keep to a rhythm or establish its semblance.

A high note held becomes sweet watery feedback.

Meanwhile Sioux surround the wagon train as

the strumming of a stringed box keeps pace.

A man’s voice: gravelly and chkchkchking,

scrapes its own voice box for musical mucus,

hears its own gradial tones in a different part of

its disaggregating body.

Then, seamless of ‘then’, quick fire slightly agitated chatter.

Cha-cha drum box trills as the voice tries to keep pace

with desperate glottals not glossaries.

Tunes and rationality are trying to break through

as the beaten box sounds in a cave near to a bird cage.

A layering of electrifying groams give inspiration

to a distorting low-end organ as another

improvised punk-folk ditty unassumes itself into

the forefront of a newly compounding emotion.

Slower now the beat box, almost whistling with

cymbal hiss as another hand-assisted vocable wavers

repeatingly, its join of loop obvious and hiatus-rough.

The voice now sings risingly to crescendos as if unaccompanied,

as if alone and beckoning an audience years and years away.

No threat of external evaluation in this ‘studio’, this minaret,

this intensified polis, this afternoon.

Ghedalia Tazartès, Les Danseurs de la Pluie, Alga Marghen Box Set. Includes the albums Une Éclipse Totale de Soleil, Diasporas, Tazartès, Tazartès’ Transports & Les Danseurs de la Pluie

[1] 'vitality affects' is Daniel Stern's phrase. Daniel N. Stern, The Present Moment In Psychotherapy And Everyday Life, Norton, 2004.

[2] Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight Of The Idols, Penguin, 1974.

[3] Jacques Ranciere, The Politics Of Aesthetics, Continuum, 2006.

[4] Daniel Stern, op cit.

For more on Guttural:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guttural

For David Fenech’s interview with Ghedalia Tazartès (in french):http://demosaurus.free.fr/demosaurus/ghedalia_Tazartès/ghedalia_tazartes_interview.htm

For distribution of Tazartès box-set:http://www.lingering.co.uk/

Junk Subjectivity

Whose round hairy silver magazine is angry? The journalistic discovery of literary value in spam emails – otherwise considered a pest – is no longer news. But if some poets endorse this view, celebrating the convention-breaching ‘wrongness’ of spam language, is this posture really as subversive as it seems? Keston Sutherland on a consumer revolt in the avant-garde’s inbox

Over the last 25 years, the phrase ‘avant-garde poetics’ has become synonymous with the banalisation of polemical language. A new orthodoxy has been scrivened into the so-called margin of aesthetics, a jargon of inauthenticity with its very own catalogue of abused nouns and outcast concepts, unvarying as the deep problems of capitalist existence that it serves to occlude. What are these nouns and concepts? Dixit jargon: they are the hangover of ‘Romanticism’. Sift through pretty much any article by Bruce Andrews and the familiar assortment of put-downs is there, icing the debris-syntax: we are against Content, The Obvious, The Smooth, ‘the transitive ideal of communicating, the direct immediate broadcast…the Truth with a capital T…usual generic architecture of signification…continuities…’ These phrases converge invariably on one principal target, the most loathsome because it is the manager of all the others. Dixit Andrews: ‘Psychology-Centered Subjective Expressiveness on the part of the Author.’ The self-proclaimed extremism of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetics, the predominant US literary avant-garde, consists, roughly speaking, in this: it is the linguistic means of producing text material to which it itself ascribes the capacity of resisting the mechanisms of interpretive consumption that homo consumer falsely and proudly believes he owns. L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry will not give its readers ‘Subjective Expressiveness’ that can be identified with the psychic operations (mood swings etc.) of an ‘Author’. It refuses to give them this Expressiveness because they take it the wrong way, i.e., as if it were propaganda or a latte; or because the state and billboards and TV use Expressiveness to sell dildos and wars; or because the mental operations of homo consumer herself cannot hit their peak freedom-rating until they are disaligned with the language most familiar to them; these and other reasons.

The dirty concept floating about in all these disjunctive anti-slogans and insurrectionary multimplications is the concept of authority. The author is authority incarnate, or a special instance of authority, and whenever he uses language that signifies or in some way projects his authority, he is complicit in the general authoritative mystification of real life on which capitalism depends and of which capitalism is the beneficiary. Fortunately, however, it is quite possible to be a poet without being an Author. All that needs to be done is for the poet to make sure that she rinses out from her language all the soddenness of authoritative syntax, grammar, diction, argumentation and, of course, Psychology-Centered Subjective Expressiveness, and bingo. Suddenly we have a materialist poetry that smashes through the logic gates of the prison-house of language and pisses into the governor’s Rolodex.

The new orthodoxy has become especially popular in the period since the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the victory of the US in the Cold War, partly because of the cautious and respectful attitudes toward L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E theory of those poets and critics, writing in that period, who set out their own ideas about aesthetics and politics more or less in opposition to L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E theory. This same period has also seen an event unparalleled in the history of communication: the English language has become the final, indomitable and universal lingua franca of global capitalism. Possibly the internet has played a greater role in this obliteration of language differences than any other engine of propaganda and commerce (and their opposites). There before the Syrian or Indonesian retina in a millisecond is a vast hinterstate of English, all linked up and laid out in the tightest integration ever possible in the history of text production, creeping steadily across the world grid like an emancipated fungus. Capitalism benefits immensely from this outreach, and English qua capitalism-logos also benefits, becoming more dominant as it becomes more prolific. But is English as a medium for anti-capitalist communication likewise invested with new potential as its enemy language becomes hugely more promiscuous? Are the possibilities for distorting and indicting the language of capitalism enlarged along with the quantity of that language pumped into the market?

Over the last year, a ripple of interest slid through the mainstream media, concerning spam e-mails and the apparently poetic character of some of the language that shows up in them. The journalists’ suggestion is always the same: as the BBC put it, ‘lots of people are starting to find literary value hidden among the porn, penis patches, generic Viagra deals and mortgage offers.’ This stuff is of course valueless in itself, the dark froth of the black market; but its victims, the passive recipients of unscrupulous Nigerian demands for bank account details and offensive invitations to look at cumshots, can find something magical in it all. Poetry. What makes this language a good raw material for amateur poetising is its wrongness: frequently it is screwed up English, a breach of conventional syntax and grammar, a funny rash of solecisms and malappropriated advert-talk. The offended western consumer can laugh it all off in rhymes and verses, converting the gibberish of Dr. Arliru Ayodele or Chief Wale Adenuga into a piece of double-edged irony, poking fun simultaneously at the authors of the spam and, with a consciousness of being postmodern, at the idea of authors in general. Who would come up with this kind of language on their own? Clearly it couldn’t be the expression of a native user of English; and so in English it looks oddly mechanical, oddly and strikingly devoid of Truth with a capital T, absurdly incapable of living up to the transitive ideal of communicating. Fraudulent pleas for help from endangered Arabs are the misjudged replicas of Psychology-Centered Subjective Expressiveness, impossible to believe or care about, an irritation pure and simple. But if the western consumer pauses for a few seconds before deleting them, they can make hilarious reading: aren’t they in fact avant-garde? Isn’t their wrongness in fact strictly semiotic, strictly a matter of signification and its fragility, and is there any reason why it can’t be taken for a sort of Brechtian alienation technique? And thus the excluded, fugitive bits of English-the-capitalism-logos are picked up and recycled to the credit (in stacks of symbolic capital) of their target consumers. A salutary poetics of consumer rights in the face of a barrage of unwanted commercial pressure.