Chapter 8: Introduction - Reality Check: Class and Immaterial Labour

Introduction to Chapter 8 of Proud to be Flesh - Reality Check: Class and Immaterial Labour

—

Mute could never be accused of remaining indifferent to the techno-utopian thinking of the mid-’90s. But, despite our enthusiasm for, and interest in, the digital explosion of the net, we always aimed to discredit those fantasies attached to ‘immateriality’, in which labour magically disappears from the production of value, and the materiality of life is somehow jettisoned. It is no accident that, for many years, our strap line was ‘Proud to be Flesh’. Mute also partook of its own share of techno-utopianism. This tended to involve visions of virtuality’s power to heal rifts of class, space, race and gender, largely through the power of disembodied global communication. But, compared to the IT-propelled wet dreams of neoliberal capitalists and state planners, entailing the mirage of a ‘weightless economy’ in which knowledge workers perform ‘immaterial labour’ to produce one ‘long boom’, those alternative visions for the network society seem almost sober. At the very least, they continued to deal with the reality of domination, even if the panacea of cyberspace was overly optimistic. Behind the seductive visions of the network society, indulged in by cyberfeminists and venture capitalist alike, however, lay greater transformations, wrought in no small part by the same technologies: The shift from the relatively even distribution of manufacturing across the globe to the West’s rapid de-industrialisation and all that this implies – an opening up of markets, expansion of supply chains and the flexibilised deployment of labour that relies heavily on IT communication networks.

The articles in this chapter strive to define these new contours of labour and capital’s ‘post-Fordist’ recomposition, while consistently trying to understand the possibilities produced for new forms of struggle. This search for a politics of resistance adequate to post-Fordist globalisation also involves, of course, much intra-left debate and disagreement. Most at issue, in the articles compiled here, are the claims made by Italian post-autonomist Marxists, such as Maurizio Lazzarato and Antonio Negri, for the radical possibilities inherent in capitalism’s increased dependency on the creativity and ‘affectivity’ of the worker. Now that repetitive, mind-numbing work is performed increasingly by robots, the argument goes, creativity and affectivity is demanded of workers – a far less controllable means of production. The erosion of boundaries between life and work is also conceived of, by Negri et al., as an opportunity as much as an incursion into free time. The net result of this thinking is that labour time – the basis of value production – becomes impossible to measure and, if labour time is no longer the basis of value, then capitalism’s underlying logic is rendered defunct. A further double-edged condition of post-Fordist labour is its precariousness, as short-term contracts, shift work and a lack of benefits and job security become the norm. This precariousness, or ‘precarity’, affects workers across sectors and classes and, for that reason, some argue, creates the possibility for new alliances. The artist, the call centre worker and the sex worker supposedly now share some of the same exploitative conditions, and possible grounds for struggle.

These articles move at speed through different theatres of production, describing them with great acuity and often humour. Arthur Kroker took one of the first stabs at defining the techno-cultural elite which he named the ‘virtual class’. In his interview with Geert Lovink, he describes how ‘the will to virtuality’ has completed the commodity’s illusory severance from its economic base, conjuring ‘the pure aestheticisation of experience’. This is a fantasy entered into by the virtual class –which also tends towards ‘liberal-fascism’ – a class committed to opening up trading zones to commodity circulation, while living in fear of migrating workers. Their aim is, baldly, to ‘suppress the working class’ says Kroker. Simon Pope, in his hilarious recreation of the internal monologues of the mid-’90s, Shoreditch digerati, ventriloquises a male pubescent mindset fixated with brands, kit, virtual and commercial combat, personal security and making money without doing any work. Pope is careful to graft the ‘weightless economy’ to its hinterland of real production: ‘Where Josh’s dad’s business was built on international trade in fossil fuels, Josh makes his wedge from the trade in cultural currency.’

In the ten or so years over which these articles were commissioned, however, there is a distinct shift in focus from the virtual class to its underclass. This underclass unites the shit work of ‘knowledge workers’ in the world’s call centres, highly exploited and indebted university students, the underpaid cleaners of Europe’s ‘progressive’ cultural institutions, the dislocated logistics workers, who supply the postmodern manufacturing industry with its array of components, and the illegal, domestic and agricultural workers, whose historical precariousness has been eclipsed by the new-found ‘precarity’ of once-secure workers. As Angela Mitropoulos reminds us, global precarity has always been the standard experience of work in capitalism. ‘Fordism,’ she writes, ‘is an exception in capitalist history’.

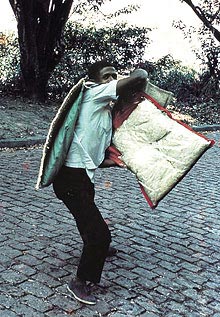

As the certainties of progress associated with Fordism crumble, so, too, does the confidence of modernity and its culture. Anna Dezeuze explores artists’ fascination with the precariousness of the global poor and their makeshift strategies of survival. The work of artists like Francis Alÿs and Marjetica Potrcˇ mimics the ‘inventiveness’ of shack dwellers and the urban poor, finding in their outsiderhood a ‘certain freedom’. In Potrcˇ’s view, ‘the world we live in today is all about self-reliance, individual initiative and small scale projects’ – something she clearly embraces. This resignation, on the part of liberals, to the postmodern impossibility of mass movements and revolutionary social change is the target of Brian Ashton’s article, ‘The Factory Without Walls’. For Ashton, the Thatcherite defeat of the left and the smashing of union militancy during the 1980s has led to the mistaken idea that production has become so globalised, its workforce so scattered and sub-contracted, that co-ordinated action is all but impossible. Uttering the maxim ‘know thine enemy’, he advocates research into the structures of contemporary capitalism and its global supply chains. ‘The mass worker hasn’t been destroyed’, he argues, ‘s/he has just been reconfigured’. By going global, he concludes, ‘capitalism is creating the opportunity for global working class struggle.’ If IT has been deployed by capitalism to recompose itself by disbanding and outsourcing the centres of proletarian production, then it can similarly be used to recombine this class again. But, what the class identity of this reconfigured mass worker actually is, on what basis struggles will be fought and what role the ‘knowledge worker’ will play in all of this is productively disputed here.

Call to Arms

In the summer of 1999 Kolinko, a group of German radicals, decided to start working in call centres, examining exploitation there and strategies for overcoming it. Three years later they published Hotlines, an invaluable document for those wanting to understand how work is carried out and resisted in call centres. The group have been criticised by some for promoting workers’ enquiry as a political project and engaging in ‘radical sociology’. Here, Kolinko reprise and defend the thinking behind their research, and one member gives a first hand account of his time working at one of the largest call centres in the UK

A RADICAL ENQUIRYThe Hotlines book describes a three year process of enquiry in call centres, attempting into understand the situation there, workers’ behaviour during and against work, conflicts, and interventions – through leaflets and otherwise. In this enquiry, we saw ourselves as workers participating in the struggles and trying to support their development. We had a guiding principle: make clear to other workers, and ourselves, the actions that are already being carried out. Our goal was not to enlighten ‘unreflective’ workers, but to push beyond our own limited horizons.

We want to grasp the standpoint of the collective social worker: the effects of technological change, the impact of the social and international division of labour on everyday life, the experiences of other workers in their struggles, and the power they develop through them. It’s about breaking up the limited perspective which the isolating capitalist organisation of work imposes on us, blocking our own view of things.

Of course, our attempts to get an overview, to understand class conflicts, and to throw our ideas into discussion – in other words, the ways and means we use for enquiries – ask for a continuous debate. We used the Hotlines questionnaire mainly for reflecting our ideas and for starting discussions with other workers. Consequently there was much they missed; it did not say much about struggles in other sectors, about crisis, and nothing about war. Better leaflets would draw the lines between the events on the shop floor or in the job centres and the global transformations of capitalism – a means to further encourage discussion among workers by supplying information on other struggles. In the worst case, they won’t read that stuff or know what to do with it; in the best case they will use it during upcoming conflicts and start to spread their own experiences through leaflets or other media.

We do not believe in the supposed separation between workers and militants/activists, one lot with their crazy revolutionary ideas, the other only interested in more money and job security. While there may be thousands of examples of the ‘individual worker’ – individualism and competition while searching for a job, demands in collective bargaining situations, racism against newly emigrated workers – there are also many examples of the opposite: the doctor’s receptionist who does not want to work in medical practices any more even if she gets paid better, because she prefers being together with larger numbers of workers in a call centre; the casual worker who doesn’t give a shit about money and security and goes surfing after four months of work. Historically there are many examples of workers who act against their economic interests – enjoying themselves by burning down their company, killing the boss and so on.

Enquiry is one method that can be used in order to understand this space between workers’ behaviour as labour power that wants to improve its conditions, and as the class that wants to put an end to exploitation. It can do this by dealing with real processes, contradictions, and tensions. Workers already make enquiries: they are interested in the wages of their foremen, conflicts in other departments, the restructuring management has planned (sometimes even in the struggles of the landless in Brazil or the unemployed in Argentina); if they don’t make such enquiries, they lose out, unprepared for the next conflict. In most cases the division between those who are interested in what’s going on and those who are not is not a division between so-called ‘revolutionaries’ and workers, but between workers themselves.

For us the issue of our exploitation corresponds directly with that of our struggle. We don’t have to tell anyone that we/they are exploited: it’s a collective effort to understand the social dimension and structure of how this exploitation is organised. We have no desire to be militants or activists, sacrificing ourselves for a historic mission, getting on everyone’s nerves including our own. Rather we make this choice: to deal with the situation collectively, rather than individually, whenever we have to sell our labour power or cope with the worsened conditions at job centres and the welfare office. For instance, we can decide together in which places of exploitation we want to earn our cash and at the same time participate collectively in conflicts. That way, our disgust for the capitalist daily routine and our anger against the conditions and those who oppress and exploit us can flow together into one common political project.

Enquiry is the condition, form and method of our attempts to understand the current struggle and to take part in it. Those who would still like to go into these questions in more detail from the perspective of our experiences should read the Hotlines book.

LONDON CALLINGI had heard a lot about call centres, day after day, for two years. I thought I knew what to expect.

The CompanyOne of the biggest market research companies in the world. They have offices or call centres in 36 countries, big multinational or government clients. For example the Australian General Union asked the company to conduct a survey about flexible work-time. They should just have asked the company’s workers – they knew all about it already.

The Call CentreThe call centre is in London, near London Bridge, in a side street facing a high red brick wall with barbed wire on top. A group of young Spanish and Italians stand in front of it, the Italians swearing about Berlusconi, the Spanish smoking weed. Two doors, one pincode, then you are inside the ‘postmodern chicken farm’ as people call it. Packed little phone booths for hundreds of interviewers. The job is market research, phoning people in France, Italy, Spain, Germany, the UK, Ireland, randomly selected by the computer. At the end of each row, the supervisors’ desks.

The ConditionsThe whole thing started with two days’ unpaid training, basic brainwashing about market research, how to use the antique computer program and so on. The second day a really nice guy from French Reunion Island came in ten minutes late and was sent home again, unpaid, but at least only half brainwashed. The stylish gay Asian supervisor, who regularly handed out anti-globalisation information and was a very welcome guest at various call-centre-workers’ parties, was able to justify giving him the sack.

After these two days you can start working – if you get your shifts. You have to book them a week in advance and if there is no work, you won’t get any. The management wanted to introduce a new shift scheme, with a top list of interviewers: whoever completes the most interviews, whoever has got the least ‘idle time’ and is the most punctual and obedient worker can choose their shifts first. If you are a miserable worker, you’ll get what’s left over. Theoretically you can book as many shifts as you want – of course there are some legal restrictions, but they don’t really count. I saw people working 12 hours a day, seven days a week, although that’s a sad exception.

The WorkIf you press ‘y’ after the computer asks you ‘another interview?’, it starts dialling random numbers. When you are lucky, you get connected to a fax machine or a modem and you can press ‘8’, just to be asked the same question again. In between ‘8’ and ‘y’ is the kingdom of idle time, but watch it – the king or queen of idle time gets into trouble. If you are connected to another human being you have to start asking questions.

Most sensible people hang up after hearing the word ‘market research’; all the others usually are very lonely, mentally unstable or just wrong in thinking they’re doing you a favour. We do surveys about alcoholic drinks, fast food chains, mobile phone networks, DVD-players and digital cameras, cars, petrol stations, post offices and more. We do it every day, ‘til nine in the evening.

Imagine phoning a small Irish village on a Sunday night asking about DVD players. At least you can hide behind your script. You are supposed to read it from the screen, word for word. How else could you possibly think of questions like ‘Imagine Burger King is a person with its own personality. Would Burger King be introverted, bold, immature or warm-hearted’? The average interview takes about 20 minutes, on average you do three to four interviews in a four hours shift, the fruit of 200-300 phone calls. Rumour has it that the company gets £70 for each interview.

The WorkersFrom all over the world, in their 20s, most of them ‘creative’ in one way or the other. It would be wrong to say that they are ‘students’, though most of them have been. You can talk about Guy Debord with a French female artist just back from Cuba, the drummer of an anarchist Italian hardcore band, a gay second generation Turkish boy from Cologne who is studying fashion design, a traditional Asian Muslim man from the East End, a girl from a village in the Alps with a population of fifty, who just arrived in London – all in a four-hour shift. I’ve never worked in a place before where people were so critical and verbally able to dismiss their work, even capitalism as such. But I have also hardly ever seen people accepting such mind-numbing work and patronising management behaviour. Because it’s just a job for a while? Because they mainly did that kind of job after quitting school or university? Because of the week-to-week shift system? I still don’t have a clue why.

The SupervisionThere is one supervisor for ten to twenty interviewers, monitoring the idle time, counting interviews and attempts, listening to what you say and how you say it. They come to your desk if you are not dialling for five minutes; they give you bad marks if you don’t stick to the script. They walk around and tell you to put your book or newspaper back into your rucksack and to bring the coffee back to the coffee machine, because hot drinks are not allowed. For an extra pound an hour and the privilege of not having to be on the phone they wear themselves out.

The SabotageIt starts with small things. Little drawings or scribbles in each phone booth. A lot of ‘Leave your brain at the entrance’ stuff. Someone is constantly stuffing the toilets with toilet rolls, so the management put out these notices: ‘Whoever is putting paper down the toilets, please stop it. It is unnecessary, unhygienic and causes inconvenience for everybody.’ The next day people cross out the ‘It’, replacing it with ‘Market Research’, or the name of the most hated supervisor.

We started collective slam poetry, handing on poem lines from neighbour to neighbour. Sometimes we used the computer as well, pressing the right combination of codes to keep the computer dialling, assuming that there are only fax machines at the other end. But that’s risky: the supervisor could be monitoring you. Sometimes, especially with lonely elderly people, we live out our social worker tendencies, talking about gardening and the new priest in the community, instead of fast food chains. Some Spanish guys developed a funny threesome, using the headset, passing the receiver on to the neighbour, so that the confused respondent talked to two interviewers. We faked management instructions that are placed in every phone booth, calling for the return of the Idle-Time King and mass orgies.

On Saturday shifts there is a higher drug consumption. That’s when most of the weird stuff happens. Receivers at the supervisors’ desks glued to the phones, people pretending to be preachers or radio show presenters. But there was never a real collective action. Once on a Saturday, 15 minutes before the end of a nine-hour shift, the supervisors circling to make sure we keep on dialling, some French girls suddenly started to cheer and applaud like crazy. All the pent-up energy broke loose and the whole call centre joined in, then packed their stuff and left five minutes early. We were never able to repeat that.

The EndIn the end, after six months, I got my fair share of disciplinary meetings, but wanted to leave anyway. It was my first and last call centre job. I found interesting people there, situations of solidarity and flirtation, a real friend. In political terms I am less sure. Maybe the most radical thing would have been to elect a shop steward or get rid of the zero-hour contracts and arbitrary management behaviour. But what for? To tie people even closer to this madness, by offering proper contracts? By that measure it would have become clear that we are workers with rights and our own interests. But why channel energy into such formally correct work relations, when there is all this disgust towards this kind of work, all this pent up creative anger?

What I missed here was a group of more experienced people, politically and job-wise, with whom to reflect on the situation. At first I thought a leaflet, for example about the new shift system, would be kind of ‘external’, so I just talked to my neighbours, made little drawings, like everyone did. But maybe something on paper, demanding a collective action and handed out to everyone would have forced all of us to define a position. Who knows..?

http://www.nadir.org/nadir/initiativ/kolinko/lebuk/e_lebuk.htm

Data Trash (The Theory of the Virtual Class)

An interview with Arthur Kroker about the virtual class, retro-fascism and the figure on the world stage of political history.

Arthur Kroker, Canadian media theorist, is the author of 'The Possessed Individual','Spasm' and 'Hacking the Future'. Over the past years he, together with Marilouise Kroker, were often in Europe and made appearances at Virtual Futures, V-2, Eldorado/Antwerpen, etc. Recently, they have also been discovered in German-speaking countries. Both are noted for their somewhat compact jargon, which made their message appear to drown somewhat in overcomplex code. But "Data Trash"`(1994) changed all that. The long treck through the squashy discourses had not been in vain. Firmly rooted in European philosophy, yet not submerged, Arthur Kroker has found his topic: the virtual class.

The ongoing world-wide commercialization of the Net gives at this moment a new sector in the economy and hence social categories. Kroker's virtual class appears to be remarkably aggresive and cynical and, as anyone can observe, would have little to do with grass roots democracy or public access issues. In today's exploding digital markets, it's grab as much as you can. Now that he has been able to define the adversary in such clear terms, Arthur Kroker understandably thriving. The critics in the media are outraged, why such pessimism? Aren't the good intentions of the media pioneers for all to see? The rapping Kroker is becoming a nuissance. Apparently he is kicking where it hurts.

Arthur Kroker wrote 'Data Trash, a Theory of the Virtual Class' together with Michael Weinstein, a poltical philosopher, rap poet and photography critic for The Chicago Tribune. According to Arthur Kroker he is also "a Nietzschian underground man who thinks deeply about the United States." Arthur and Michael met during the Vietnam years and collaborated for the last 20 years on the Canadian Journal for Poltical and Social Theory (now the electronic magazine 'CTHEORY'). 'Data Trash' is hyper topical, which is remarkable for such a slow medium as a book. It leaves manuals, introductions and speculations behind in order to operate a pincer movement, telling the story of the rise of a new class while at the same time reflecting upon its consequences. This is a far cry from the usual activities of media theorists for whom the Net is still more something of a rumour than of a concrete experience.

I asked Arthur Kroker how his book how it is that his book can be so topical and reflective at the same time. "My body does a lot of travelling. I like to take deep plunges in the San Francisco spreading psychosis. I visit MIT and the Boston area and I spend time in Europe as well, roaming between Grenoble and Munich, to understand the cybermatrixes. And I spend a lot of time in the Net." 'Data Trash' was written on the Net, the writers haven't seen each other face to face in five years. "We experienced that there was a third person, the third mind, who wrote the book. The computer had come alive and 'Data Trash' was the result."

The cultural strategy followed in this book is called 'Hacking the Media'. "We like the notion of overidentifying with the feared and desired object, to such a point of obsession that you begin to take a bath in its acid juices. You travel so deeply and quickly in cyberculture that you force it to do things it never wanted to. I try to live my philosophy through cyberculture." For Michael Weinstein too it was an unique situation because he is mostly outside of the glowing horizon of technoculture and does not live in the corporate capital of America. He dwells in the twilight zone of Chicago which produces rough midwestern thinkers, who reflect on the howling winds of sacrificial violence and the decline of the American empire.

Why does this emerging class does not have a class conciousness of its own?

Arhtur Kroker: "If it did it would be doomed as the emergent class. 'Data Trash' is on suicidal and passive nihilism, as the radical Nietzsche predicted it in his 'Genealogy of Morals'. Virtual Reality means to us the humiliating reduction of human beings to servo mechanisms, or as Heidegger would say: as a standing reserve. The humiliation of the flesh as you are poked and proved and sucked by the harvesting machines of the virtual reality scanners."

Virtual reality does not mean head-mounted scanners and data gloves to Kroker & Weinstein. In their terminology VR is a whole assemblage of experiences, involving a traditional class consiousness, the spread of the ideology of techno culture and the hegemony of 'liberal fascism' and its swing back into 'retro fascism' as the political force behind the so-called 'Will to Virtuality'. 'Data Trash' seems the purest consummation of marxism, the severance of the commodity form from its economic base, into the notion of the pure estheticization of experience. Arthur: "We talk about the recombinant commodity form, in an economy run by the biological logic of cloning, displacing and resequencing. Or virtualized exchange, the replacement of a consumer culture by the desire to simply disappear, from shopping to turning your body into a brand name sign."

Now that the Berlin wall has crumbled and everyone left marxism, Kroker & Weinstein have gone back to Marx for a close reading of the movement of capitalism into the phase of pure commoditization. Living in America is not a question of trying to catch up with the media. The body is always moving to the speed of the media itself. 'Data Trash' begins with two fundamental rejections: the techno-utopian stance taken by Rheingold in his book 'Virtual Communities' (not the same Rheingold than after his 'Hot Wired' experience) and Neil Postman's neo-conservative position. On the other hand, it critiques all brands of technological determinism, who state that we don't have choices. There are real contradictions and lots of fractures, even in the supposedly closed virtual class. For Kroker/Weinstein, the field of political contestation is wide open.

But is this class in itself, not already virtual, in the sense of being invisible, dispersed and without clearly formulated class interests?

"We have done our investigations in many countries, to try to understand the different class fractions. How would the virtual class be actualized in France as opposed to America or Canada? In every case it turns out to be this curious mixture of predatory capitalism and computer visionarism. But it strikes us that it is a coherent class with pretty straightforward ideological objectives. It has to suppress the working class. In North-America one should position it within the framework of the NAFTA agreements. It freezes the working class and lower middle class in place so that they cannot move easily over national borders. When the workers complain, then they bring in the mechanism of a disciplinary state, the pinitive side of the virtual class.

"It's commenplace rethoric now: they have to stampede everybody on the information superhighway, and every business man knows that if you're not going on it soon, you are going to be eliminated, economically and historically. And this whole notion has been appropriated by the virtual class. But at the same time it is not a traditional class because it does not operate in the traditional logic of the political economy. The very notion of capitalism has already mutated, not really into technology, but into virtuality. Our work is a prolegomenon to the study of the virtual class, about the coming to be of a much more sinister and demonic force and that's the 'Will to Virtuality', a deeply disturbing, nihilistic aspect of the culture in which we live. It's about this suicical urge to feed human flesh into image processing machines, in such intensity, hyper accelaration, and suicidal seductiveness that flesh appears humiliated before it.

In the end you have to choose for an existance as a 'honoured collaborator', in Whitehead's sense, of techno-culture, rather than not to act at all. For a lot of thinkers, the position of the human species as 'honoured collaborator' of techno-culture, is their idea of a modernist position, what I call 'technological emergentism'. The human species is being superseded by technology. All right they say (the Shannons, McLuhans, etc.), but we still can be a honoured collaborator, we can probe around the world, and we can have media extensions of man. The notion of exteriorization is the possiblity of discovering new religious epifanies of technological experience. We reject that perspective. It is not about 'reaching out' but about 'reaching in'.

How does the vitual class relate to neo-liberalism?

"The political program of the virtual class goes way beyond the Reagonomics and Thacherism of the eighties. The agenda of the corporate class is to remove all barriers for the transnational movement of products. The knowlegde industry, which is computer based, should also move freely and universally. The technocratic class is not so much conservative as liberal. It stands in opposition to national political forces that would obstruct pure transnationalism. President Bill Gates and President Bill Clinton have a common class ambition, that is to get everyone on the cybernet as fast as possible, through 'policies of facilitation'. Cyberspace promises better communication, greater interactivity, speed: a whole seductive rethoric is on offer. Once everyone is on, there's going to be privatization, what we call the 'politics of consolidation': shutting down the Net in favour of commercial interest or pay in order to have your body accessed.

Yet to outsiders this virual class doesn't appear at all to have an aggressive policy. Its daily work, writing software, seems to be pretty dull and harmless.

"A chacarteristic of the virtual class is that it is autistic. It's an absolute meltdown of human beings into these autistic, historically irresponsable positions, with a sexuality of juvenile boys and being happy with machines. Shutting down the mental horizon while communicating at a global level and preaching disappearance. And why not, because you've already disappeared yourself... But as the guide at Xerox Parc said, "Who needs the Self anyway?" Privacy for these people has always been imposed on human beings by corporations, it's not something they claim they wanted. The Xerox Parc of the future is not about copying paper anymore, but copying bodies into image processing machines. And who needs privacy in such a situation?

The other mental characteristic of the virtual class is that it is deeply authoritarian. It believes that virtuality equals the coming to be of a fully free human society. As CEOs of leading corporations use to say, "adapt or you're toast" and they utter this with the total smuggness of complacency itself. The other side of cyber-authoritarianism is the absolute outrage that grips them in the presence of opposition. Qualms about the emergence of the virtualclass, or about the social consequences of technology are met with either indifference or total outrage. Quite on the contrary, members of the virtual class see themselves as the missionaries of the human race itself, the advant garde, in their terms, of the honourful collaboration with the telematic machines.

The virtual class has this aspect of seduction and the on the other hand the policy of consolidation, which is the present reality in which we live. It is a grim and severe and deeply fascistic class because it operates by means of the disciplinary state, imposing real austerity programs in order to fund the research efforts benefitting to itself. At the same time it controls politically the working classes by severe taxation in order to make sure that people cannot be economically mobile and cannot accumulate capital in their own right. When it comes to Third World nations they act in classic fascist way. They impose strict anti-emigration policies in the name of humanistic gestures. They shield their own local populace from the influx of immigrants bycreating a 'bunker state', by going for a Will to Purity.

We're not dealing here with a 'Will to Power' or a 'Decline of the Western Society' but with a 'Recline of the West' and a 'Will to Virtuality'. The recliner is a new representative persona on the stage of world history. The recliner is the best captured by the US tv-series, 'The Simpsons'. "Just blame it on the guy who doesn't speak English, oh, he works for me." Truely retro-fascist ideas put it the mouth of cartoon characters. Bill Clinton is the perfect representative of the weak will, full of moral vascilations, yet authoritarian at the same time.

Still, you are not moving into a technophobic position, you use computers yourself and enjoy them. How can we make a distinction between the goals of this virtual class and opposite, alternative ways of using technologies?

"I have to be honest with myself and it's hard to think of life without computers. I genuinely believe that these technologies, on the base of real struggle and reflexion, do offer alternative possibilities from domination, towards certain forms of emancipation. 'Data Trash' is also written as a manifesto for the coming to be of geek flesh, a realistic look at the world.

It would be interesting to look at the role of traditional political strategies in cyberspace itself. For example the notion of 'Squatting the Media' for me is a fundamental point of media contestation and a theory in itself. Just as interesting would be the question of subversive forms of sexuality in cyberspace itself, like what the cyber-feminist group 'VNS-Matrix' from Australia is doing. Try to make the stable science systems as unstable as possible to open up possiblities for ambiguity and paradox and for the reversal of reversionary mechanisms. That is done now through these playfull but deadly serious interventions into the media-net itself, enriched with imagination. It attacks the system exactly in its own language and opens up possibilities for democratic consensus, without in any waybeing dogmatic.

'Squatting the Media' after all is politically significant, but it does not want to be explicit about it. When Karl Jaspers wrote 'Man and the Modern Condition' he said that the fundamental act of political rebellion today is the human being who refuses, who says no. It marks the end of any hegemonic ideological position and the beginning of politics again. 'Squatting the Media' represents a refusal and marks a return of morality into politics. It would be important to take practical examples of subversive intentions that operate deeply in cybernetic language itself, not outside of the media-net but inside it.

Geert Lovink

Arthur Kroker, Michael A. Weinstein, Data Trash, the Theory of the Virtual Class, St. Martin's Press, New York, 1994.

CTHEORY is available, free, by email, send a message to <ctheory-request AT concordia.ca> with the word "subscribe" in the body of the message.You can contact CTHEORY through <ctheory AT vax2.concordia.ca>

Precari-us?

Does the term precariousness or 'precarity', as applied to the conditions of employment under neoliberalism, provide us with more than another trendy neologism? Angela Mitropoulos examines its use, misuse and associated political horizons

Few could be unaware that an increasing proportion of the workforce is engaged in intermittent or irregular work. But I'd like to set aside for the moment the weight and scope of the evidentiary, those well-rehearsed findings that confirm beyond doubt the discovery and currency of precariousness and which render the axiomatic terrain upon which such facts are discovered beyond reproach. Instead, I would like to explore something of the grammar at work in these discussions. As a noun, 'precariousness' is both more unwieldy and indeterminate than most. If it is possible to say anything for certain about precariousness, it is that it teeters. This is to begin by emphasising some of the tensions that shadow much of the discussion about precarious labour. Some of those tensions can be located under various, provisional headings which bracket the oscillation between regulation and deregulation, organisation and dissemination, homogenous and concrete time, work and life.

There are notable instances of this: consider recent research commissioned by Australia's foremost trade union body, the ACTU, into what they call 'non-standard' forms of work. As reported, most of those surveyed said they would like 'more work.' It is not clear to what extent that answer was shaped by the research, i.e.: by the ACTU's persistent arguments for a return to 'standard hours,' re-regulation, or their more general regard for Fordism as the golden age of social democracy and union organisation. 'Non-standard work' has mostly been viewed by unions as a threat, not only to working conditions but, principally, to the continuing existence of the unions themselves.

But what is clear is that the flight from 'standard hours' was not precipitated by employers but rather by workers seeking less time at work. This flight coincided with the first wave of an exit from unions. What the Italian Workerists dubbed 'the refusal of work' in the late 1970s had its anglophone counterpart in the figure of the 'slacker'. This predated the 'flexiblisation' of employment that took hold in the 1980s. The failure of this oppositional strategy nevertheless provoked what Andrew Ross has called the 'industrialisation of bohemia'. Given that capitalism persisted, the flight from Fordist regularity and full time work can be said to have necessitated the innovation and extension of capitalist exploitation much like gentrification has followed university students around suburbs and de-industrialising areas since the 1970s.

The search for a life outside work tended to reduce into an escape from the factory and its particular forms of discipline. And so, perhaps paradoxically, this flight triggered an indistinction between work and life commensurate with the movement of exploitation into newer areas. This is why the answer of 'more work' now presents itself so often as the horizon of an imaginable solution to the problem of impoverishment and financial instability not more money or more life outside work, but more work.

Take the distinction between work-time and leisure-time. These categories become formalised with Fordism, its temporal rhythm as measured out by the wage, clock and assembly line, and distinguished by a proportionality and particular division of times, as in the eight hour day and the five day week. Here, leisure-time bears a determined relationship to work as the trade-off for the mind-numbing tedium of the assembly line, as rejuvenation, and as temporary respite from the mind-body split that line-work enforces. Yet leisure time was, still, substantively a time of not-work.

By comparison, while the perpetually irregular work of post-Fordism might, though not necessarily, decrease the actual amount of time spent doing paid work, it nevertheless enjoins the post-Fordist worker to be continually available for such work, to regard life outside waged work as a time of preparation for and readiness to work. Schematically put: whereas Fordism sought to cretinise, to sever the brains of workers from their bodies so as to assign thought, knowledge, planning and control to management, post-Fordist capitalism might by contrast be characterised in Foucault's terms as the imprisonment of the body by the soul. Hence the utility of desire, knowledge, and sociality in post-Fordism.

The long, Protestant history of assuming work as an ethical or moral imperative returns in the not-always secular injunction to treat one's self as a commodity both during and outside actual work time. One can always try to defer the ensuing panic and anxiety with pharmacology, as Franco Berardi argues. But something might also be said here about that other 'opiate,' the parallel rise of an enterprising, evangelical Christianity; not to mention attempts to freeze contingency in communitarianism, of one variant or another. The precariousness of life experienced all the more insistently because life depends on paid work tends to close the etymological distance between prayer (precor) and the precarious (precarius).

PRECARIOUS SUBJECTS

The term 'Precarity' might have replaced 'precariousness' with the advantage of a prompt neologism; yet both continue to be burdened by a normative bias which seeks guarantees in terms that are often neither plausible nor desirable. Precariousness is mostly rendered in negative terms, as the imperative to move from irregularity to regularity, or from abnormality to normality. That normative burden is conspicuous in the grammatical development from adjective to noun: precarious to precariousness, condition to name.

Yet, capitalism is perpetually in crisis. Capital is precarious, and normally so. Stability here has always entailed formalising relative advantages between workers, either displacing crises onto the less privileged, or deferring the effects of those crises through debt. Moreover, what becomes apparent in discussions on precariousness is that warranties are often sought, even by quite different approaches, in the juridical realm. The law becomes the secularised language of prayer against contingency. This assumes a distinction between law and economy that is certainly no longer, if it ever was, all that plausible. It is not clear, therefore, whether the motif of precariousness works to simply entice a desire for its opposite, security, regardless if this is presented as a return to a time in which security apparently reigned or as a future newly immunised against precariousness.

There are nationalist denominations. Precarity (or precarité), in its current expression, emerged in French sociology and its attempts to grasp the convergence of struggles by unemployed and intermittent workers in the late 1990s. Most prominently, Bourdieu was among those who raised the issue of a diffuse precarité as an argument for the strengthening of the Nation State against this, as well as the globalisation that was said to have produced it. In its far less nationalist versions, the discussion on precarity is marked sometimes ambivalently and not always explicitly by the presentation of a hoped-for means of resistance, if not revolution. A renewed focus on changing forms of class composition or new subjectivities may have brought with it an irreversible and overdue shift in perspective and vocabulary. But that shift has not in all cases disturbed the structural assumptions of an orthodox Marxism in the assertion of a newer, therefore more adequate, vanguard. Names confer identity as if positing an unconditional presupposition. Like all such assertions, it is not simply the declaration that one has discovered the path to a different future in an existing identity that remains questionable. More problematically, such declarations are invariably the expression and reproduction of a hierarchy of value in relation to others.

For instance, if Lenin's Party, defined as the figure of the 'revolutionary intellectual', paid homage to the mind-body split of Fordism and Taylorism (where others were either cast as a 'mass' or, where actively oppositional, 'counterrevolutionaries'), to what extent has the discussion on precarious labour avoided a similar duplication of segmentation and conformism? Or, to put the question in classical Marxist terms: to what extent can an identity which is immanent to capitalism (whether 'working class' or 'multitude') be expected to abolish capitalism, and therefore its very existence and identity? Does a politics which takes subjectivity as its question and answer reproduce a politics as the idealised image of such? A recourse to an Enlightenment Subject replete with the stratifications which presuppose it, and ledgered according to its current values (or valuations), not least among these being the distinction between paid and unpaid labour.

Let me put still this another way: the discussion of the precarious conditions of 'creative labour' and the 'industrialisation of bohemia' tends to restage a manoeuvre found in Puccini's opera La Boheme. Here, a bunch of guys (a poet, philosopher, artist and musician) suffer for their art in their garret. But it is the character of Mimi the seamstress who talks of fripperies rather than art who furnishes Puccini and our creative heroes with the final tragedy with which to exalt that art as suffering and through opera. The figure of the artist (or 'creative labourer') may well circulate, in some instances, as the exemplary figure of the post-Fordist worker precarious, immaterial and so on but this requires a moment in which the precarious conditions of others are declared to be a result of their 'invisibility' or 'exclusion'.

For what might turn out to have been the briefest of political moments, the exemplary figure of precariousness was that of undocumented migrant workers, without citizenship but nevertheless inside national economic space, and precarious in more senses than might be indicated by other uses of the word. And, far from arriving with the emergence of newer industries or subjectivities, precarious work has been a more or less constant feature of domestic work, retail, 'hospitality,' agriculture, sex work and the building industry, as well as sharply inflecting the temporal and financial arrangements which come into play in the navigation of child-rearing and paid work for many women. But rather than shaking assertions that the 'precariat' is a recent phenomenon, through the declaration that such work was previously 'invisible', the apprehension of migrant, 'Third World' and domestic labour seems to have become the pretext for calls for the reconstruction of the plane of visibility (of juridical recognition and mediation) and the eventual circulation and elevation of the cultural-artistic (and cognitive) worker as its paradigmatic expression. The strategy of exodus (of migration) has been translated into the thematics of inclusion, visibility and recognition.

On a global scale and in its privatised and/or unpaid versions, precarity is and has always been the standard experience of work in capitalism. When one has no other means to live than the ability to labour or even more precariously, since it privatises a relation of dependency to reproduce and 'humanise' the labour publicly tendered by another, life becomes contingent on capital and therefore precarious.

The experience of regular, full-time, long-term employment which characterised the most visible, mediated aspects of Fordism is an exception in capitalist history. That presupposed vast amounts of unpaid domestic labour by women and hyper-exploited labour in the colonies. This labour also underpinned the smooth distinction between work and leisure for the Fordist factory worker. The enclosures and looting of what was once contained as the Third World and the affective, unpaid labour of women allowed for the consumerist, affective 'humanisation' and protectionism of what was always a small part of the Fordist working class. A comparably privileged worker who was nonetheless elevated to the exemplary protagonist of class struggle by way of vanguardist reckonings. Those reckonings tended to parallel the valuations of bodies by capital, as reflected in the wage. The 'lower end' of the (global) labour market and divisions of labour impoverishment, destitution or a privatised precariousness were accounted for, as an inherent attribute of skin colour and sex, as natural. In many respects, then, what is registered as the recent rise of precarity is actually its discovery among those who had not expected it by virtue of the apparently inherent and eternal (perhaps biological) relation between the characteristics of their bodies and their possible monetary valuation a sense of worth verified by the demarcations of the wage (paid and unpaid) and in the stratification of wage levels.

BIOPOLITICAL ARITHMETIC

To be sure, there are important reasons to continue a discussion of precarious labour and precarity, of how changes to work-time become diffused as a disposition. Precarity is a particularly useful way to open a discussion on the no longer punctual dimensions of the encounter between worker and employer, and how this gives rise to a generalised indistinction between the labour market, self, relationships and life.

The more interesting aspect of this discussion is the connection made between the uncertainty of making a living and therefore the uncertainty of life that is thereby produced in its grimly mundane as well as horrific aspects: impoverishment, as both persistent threat and circumstance; the 'war on terror'; the internment camps; 'humanitarian intervention', and so on. In this, the topic of biopolitics re-emerges with some urgency or rather this urgency becomes more tangible for that privileged minority of workers (or 'professionals') who were previously unfamiliar with its full force. Impoverishment and war pronounce austere verdicts upon lives reckoned as interchangeable and therefore at risk of being declared superfluous. What does it means to insist here, against its capitalist calculations, on the 'value of life'?

This raises numerous questions. What are the intersections between economic and political-ethical values? Does value have a measure, a standard by which all values (lives) are calculated and related? Transformed into organisational questions: how feasible is it to use precarity as a means for alliances or coalition-building without effacing the differences between Mimi and the Philosopher, or indeed reproducing the hierarchy between them? Is it in the best interests for the maquiladora worker to ally herself with the fashion designer? Such questions cannot be answered abstractly. But there are two, perhaps difficult and irresolvable questions that might be still be posed.

First, what are the specific modes of exploitation of particular kinds of work? If the exploitation and circulation of 'cognitive' or 'creative labour' consists, as Maurizio Lazzarato argues, in the injunction to 'be active, to communicate, to relate to others' and to 'become subjects', then how does this shape their interactions with others, for better or worse? How does the fast food 'chainworker', who is compelled to be affective, compliant, and routinised not assume such a role in relation to a software programming 'brainworker', whose habitual forms of exploitation oblige opinion, innovation and self-management? How is it possible for the latter to avoid assuming for themselves the specialised role of mediator let alone preening themselves in the cognitariat's mirror as the subject, actor or 'activist' of politics in this relationship? To what extent do the performative imperatives of artistic-cultural exploitation (visibility, recognition, authorship) foreclose the option of clandestinity which remains an imperative for the survival of many undocumented migrants and workers in the informal economy?

Secondly, why exactly is it important to search for a device by which to unify workers however plurally that unity is configured? Leaving aside the question of particular struggles say, along specific production chains it is not all that clear what the benefits might be of insisting that precarity can function as this device for recomposing what was in any case the fictitious and highly contested unity of 'the working class'. To be sure, that figure is being challenged by that of 'the multitude', but what is the specific nature of this challenge?

Ellen Rooney once noted that pluralism is a deeper form of conformism: while it allows for a diversity of content, conflict over the formal procedures which govern interaction are off-limits, as is the power of those in whose image and interest those rules of interaction are constituted. Often, this arises because the procedures established for interaction and the presentation of any resulting 'unity' are so habitual that they recede beyond view. Those who raise problems with them therefore tend to be regarded as the sources of conflict if not the architects of a fatal disunity of the class. A familiar, if receding, example: sexism is confined to being a 'women's issue', among a plurality of 'issues,' but it cannot disrupt the form of politics.

What then is the arithmetic of biopolitics emerging from the destitution of its Fordist forms? If Fordist political forms consecrated segmentations that were said to inhere, naturally, in the difference of bodies, then what is post-Fordism's arithmetic? Post-Fordism dreams of the global community of 'human capital', where differences are either marketable or reckoned as impediments to the free flow of 'humanity' as or rather for capital. In short, political pluralism is the idealised version of the post-Fordist market.

It might be useful here to specify that commodification does not consist in the acts of buying and selling which obviously predate capitalism. Rather, commodification means the application of a universal standard of measure that relates and reduces qualitative differences of bodies, actions, work according to the abstract measure of money. Abstract equivalence, without its idyllic depictions, presupposes and produces hierarchy, exploitation and violence. Formally, which is to say juridically: neither poor nor rich are allowed to sleep under bridges.

What does it mean, then, to argue that the conditions of precarious workers might be served by a more adequate codification of rights? It does not, I think, mean that our conditions will improve or, rather, be guaranteed by such. Proposals for 'global citizenship' by Negri and Hardt are predated by the global reach of a militaristic humanitarianism that has already defined its meaning of the convergence between 'human rights' and supra-national force. Similarly, a 'basic income' has already been shown, in the places it exists such as Australia, to be contingent upon and constitutive of intermittent engagements with waged work, if not forced labour, as in work-for-the-dole schemes. The latter policy was applied to unemployed indigenous people before it became a recent measure against the unemployed generally. Basic incomes do not suspend the injunction to work often in low paid, casual or informal jobs; they are deliberately confined to levels which provide for a bare life but not for a livelihood. The introduction of work-for-the-dole schemes indicate that, where 'human capital' does not flow freely as such, policy (and pluralism) will resort to direct coercion, cancelling the formally voluntary contract of wage labour. The introduction of the work-for-the-dole scheme for indigenous people in Australia followed on the collapse in their employment rates after the introduction of 'equal pay' laws. Their 'failure to circulate' was explained as an inherent, often biological, attribute (chiefly as laziness) and, therefore, the resort to forced labour was rendered permissible by those politicians who most loudly proclaimed their commitment to multiculturalism and the reconciliation of indigenous and 'settler' Australians.

So, how might it be possible to disassociate the value of life from the values of capital? Or, with regard to the relation between a globalised nationalism and aspirations for supra-national arrangements: how to sever the various daily struggles against precariousness from the enticements of a global security-state? Rights are not something one possesses even if many of us are reputed, by correlation, to possess our own labour in the form of an increasingly self-managed or self-employed exploitation. Rights, like power, are exercised, in practice and by bodies. As juridical codes, they are both bestowed and denied by the state, at its discretion. There are no guarantees and there will always be a struggle to exercise particular rights, irrespective of whether they are codified in law. But, as a strategy, the path of rights means praying that the law or state might distribute rights and entrusting it with the authority and force to deny them.

That said, precarity might well have us teetering, it might even do so evocatively, for better and often worse, praying for guarantees and, at times, shields that often turn out to be fortresses. But it is yet to dispense with, for all its normative expressions, a relationship to the adjective: to movement, however uncertain. 'Precarious' is as much a description of patterns of worktime as it is the description, experience, hopes and fears of a faltering movement in more senses than one, and possibly since encountering the limits of the anti-summit protests. This raises the risk of movements that become trapped in communitarian fears or in dreams of a final end to risk in the supposedly secure embrace of global juridical recognition. Yet, it also makes clear that a different future, by definition, can only be constructed precariously, without firm grounds for doing so, without the measure of a general rule, and with questions that should, often, shake us particularly what 'us' might mean.

Angela Mitropoulos <s0metim3s AT optusnet.com.au> sometimes produces websites http://antimedia.net/xborder http://woomera2002.antimedia.net http://flotilla2004.com, writes on border policing and class composition, and sometimes comes across a wage

Reality check: Are We Living In An Immaterial World?

Immaterial Labour is seen by (post)Marxists and capitalists alike as the motor of the new economy. Steve Wright recovers Marx's theory of value from critics such as Antonio Negri to ask whether it is as 'immeasurably' productive as is claimed?

A priest once came across a Zen master and, seeking to embarrass him, challenged him as follows: ‘Using neither sound nor silence, can you show me what is reality?’ The Zen master punched him in the face.1 Continued assertions that, today, we live in a knowledge economy or society raise many questions for reflection. In the next few pages, I want to discuss some aspects of these assertions, especially as they relate to the notion of immaterial labour. This term has developed within the camp of thought that is commonly labelled ‘postworkerist’, of which the best known exponent is undoubtedly Antonio Negri. While its roots lie in that branch of postwar Italian Marxism known as operaismo (workerism), this milieu has rethought and reworked many of the precepts developed during the Italian New Left’s heyday of 1968-78. If anything, it was the very defeat of the social subjects with which operaismo had identified – first and foremost, the so-called ‘mass worker’ engaged in the production of consumer durables through repetitive, ‘semi-skilled labour’ – that led Negri and others to insist that we are embarked upon a new age beyond modernity.2

According to this view of the world, a quite different kind of labour is currently either hegemonic amongst those with nothing to sell but their ability to work – or, at the very least, is well on the way towards acquiring such hegemony. Secondly, capital’s growing dependence upon this different – immaterial – labour has serious implications for the process of self-expanding abstract labour (value) that defines capital as a social relation. While Marx had held that the ‘socially-necessary labour-time’ associated with their production provided the means by which capital could measure the value of commodities (and so the mass of surplus value that it hoped to realise with their sale), Negri, on the other hand, is of the opinion that in a time of increasingly complex and skilled labour, and of a working day that more and more blurs the boundaries with (and ultimately colonises) the rest of our waking hours, value can no longer be calculated. As he put it a decade ago, in such circumstances the exploitation of labour still continues, but ‘outside any economic measure: its economic reality is fixed exclusively in political terms.’3

This is pretty esoteric stuff, particularly the arguments over the measurability (or otherwise) of value. Should we care one way or the other? What I hope to show below is that for all their apparent obscurity, these debates matter. That is because they raise questions as to how we understand our immediate context, including how we interpret the possibilities latent within contemporary class composition. Is one sector of class composition likely to set the pace and tone in struggles against capital, or should we look instead towards the emergence of ‘strange loops … odd circuits and strange connections between and among various class sectors’ (as Midnight Notes once suggested) as a necessary condition for moving beyond ‘the present state of things’?

Unpacking immaterial labour

Maurizio Lazzarato’s discussion of ‘Immaterial Labour’ was perhaps the first extended treatment of the topic to appear in English. Part of an important anthology of Italian texts published in the mid ‘90s, Lazzarato’s work defined the term immaterial labour as ‘labour that produces the informational and cultural content of the commodity.’4 If the ‘classic’ forms of this labour were represented in fields like ‘audiovisual production, advertising, fashion, the production of software, photography, cultural activities, and so forth’, those who perform such work commonly found themselves in highly casualised, precarious and exploited circumstances, as part of what, more recently and in certain Western European radical circles, has come to be called the ‘precariat’.5

The Taylorist approach to production that confronted the mass worker had decreed that ‘you are not paid to think’. With immaterial labour, Lazzarato argued, management’s project was different. In fact, it was even more totalitarian than the earlier rigid division between mental and manual labour (ideas and execution), because capitalism seeks to involve even the worker’s personality within the production of value.6

At the same time this managerial approach carried real risks for capital, Lazzarato believed, since capital’s very existence was placed in the hands of a labour force called upon to exercise its creativity through collective endeavours. And unlike a century ago, when a layer of skilled workers likewise stood at the centre of key industries, yet largely cut off from the unorganised ‘masses’, today ‘immaterial labour’ could not be understood as the distinctive attribute of one stratum within the workforce. Instead, skilled labour is present (even if only in latent form) amongst broad sectors of the labour market, starting with the young.

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s Empire – a book that has come to stand (rightly or wrongly) as the centrepiece of postworkerist thought – built upon and modified Lazzarato’s work. Accepting the premise that immaterial labour was now central to capital’s survival (and by extension, to projects that aimed at its extinction), Hardt and Negri identified three segments of immaterial labour:

a) the reshaped instances of industrial production which had embraced communication as their lifeblood; b) the ‘symbolic analysis and problem solving’ undertaken by knowledge workers; c) the affective labour found above all within the service sector.7

These experiences, it was conceded, could be quite disparate: knowledge workers, for example, were divided between high-end practitioners with considerable control over their working conditions, while others engaged in ‘low-value and low-skill jobs of routine symbol manipulation’.8 Nonetheless a common thread did exist between the three elements. As instances of service work, none of them produced a ‘material or durable good’. Moreover, since the output was physically intangible as a discrete object, so the labour that produced it could be designated as ‘immaterial’.9

How can we make sense of such arguments? Doug Henwood, who praised Empire for the verve and optimism of its vision, was nonetheless moved to add:

Hardt and Negri are often uncritical and credulous in the face of orthodox propaganda about globalization and immateriality … They assert that immaterial labour – service work, basically – now prevails over the old-fashioned material kind, but they don’t cite any statistics: you’d never expect that far more Americans are truck drivers than are computer professionals. Nor would you have much of an inkling that three billion of us, half the earth’s population, live in the rural Third World, where the major occupation remains tilling the soil.10

Nick Dyer-Witheford has likewise registered a number of concerns with Hardt and Negri’s account of class composition.11 To his mind, Empire glosses over the tensions between the three class fragments it identifies, while ultimately reading immaterial labour only through the lenses of its high-end manifestations. And was all of this really as new as Hardt and Negri intimated? It’s not as if ‘affective labour’, for instance, was anything but fundamental to social reproduction in the past, even if it did go unnoticed – because of its largely gendered composition perhaps – in many social analyses.

Another issue concerns Empire’s insistence that ‘the cooperative aspect of immaterial labour is not imposed or organised from the outside’.12 Again, perhaps this is true for some work at the high-end. But does the obligation to ask ‘Do you want fries with that?’ really represent a break with Fordist work regimes? Or might many of the McJobs that are prevalent in the lower depths of so-called immaterial production be better characterised as ‘the Taylorised, deskilled descendants of earlier forms of office’ and other service work?13

More recently, Hardt and Negri have attempted to address some of their critics in Multitude, the 2004 sequel to Empire. The first thing to note here is that while immaterial labour remains a central pivot within the book’s arguments, it is presented in a rather more cautious and qualified form than before. Indeed, Hardt and Negri are at pains to state that:

a) ‘When we claim that immaterial labour is tending towards the hegemonic position we are not saying that most of the workers in the world today are producing primarily immaterial goods’; b) ‘The labour involved in all immaterial production, we should emphasise, remains material – it involves our bodies and brains as all labour does. What is immaterial is its product.’14

Therefore, much like the ascendance of the multitude itself, here the hegemony of immaterial labour as the reference point, or even vanguard, for ‘most of the workers in the world today’ is flagged as a tendency, albeit one that is inexorable. Towards the end of Multitude’s discussion of immaterial labour, Hardt and Negri insist upon what they call a ‘reality check’ – ‘what evidence do we have to substantiate our claim of a hegemony of immaterial labour?’15 It’s the moment we’ve all been waiting for, and unfortunately the half a page of discussion they proffer is something of a damp squib: an allusion to US Bureau of Statistics figures which indicate that service work is on the rise; the relocation of industrial production ‘to subordinate parts of the world’, said to signal the privileging of immaterial production at the heart of the Empire; the rising importance of ‘immaterial forms of property’; and, finally, the spread of network forms of organisation particular to immaterial labour.16 Call me old-fashioned, but something more than this is needed in a book of 400 plus pages dedicated to understanding their claims regarding latest manifestation of the proletariat as a revolutionary subject…

Their reference to the growth in service sector activity is interesting for a number of reasons. Huws argues that the unrelenting rise in service work within the West might be cast in a different light if the domestic employment so common 100 years ago was factored into the equation.17 Writing a decade earlier, Sergio Bologna suggested that certain forms of work only came to be designated as ‘services’ within national statistics after they had been outsourced; previously, when they had been performed ‘in house’, they had counted as ‘manufacturing’.18 Neither author is seeking to deny that important shifts have occurred within the global economy, starting with countries like Britain, Australia, Canada and the United States. Yet they urge caution in how we interpret the changes, and care in the categories used to explain them. Bologna – a one-time collaborator with Negri in a variety of political projects back in the ’60s and ’70s – is particularly caustic about the notion of immaterial labour, labelling it a ‘myth’ that more than anything else obscures the lengthening of the working day.19

Goodbye to value as measure?

As stated earlier, one of the distinguishing features of postworkerism is the rejection of Marx’s so-called ‘law of value’. George Caffentzis reminds us that Marx himself rarely spoke of such a law, but there is also no doubt of his opinion that, under the rule of capital, the amount of labour time socially necessary to produce commodities ultimately determined their value.20 In breaking with Marx in this regard, postworkerists draw some of their inspiration instead from a passage in the Grundrisse known as the ‘Fragment on Machines’. This envisages a situation, in line with capital’s perennial attempt to free itself from dependence upon labour, where knowledge has become the lifeblood of fixed capital, and the direct input of labour to production is merely incidental. In these circumstances, Marx argues, capital effectively cuts the ground from under its own feet, for ‘As soon as labour in the direct form has ceased to be the great well-spring of wealth, labour time ceases and must cease to be its measure, and hence exchange value [must cease to be the measure] of use value’.21

Negri, among others, has insisted for many years, and in a variety of ways, that capital has now reached this stage. Therefore, nothing but sheer domination keeps its rule in place: ‘the logic of capital is no longer functional to development, but is simply command for its own reproduction’.22 In fact a range of social commentators have evoked the ‘Fragment on Machines’ in recent times – apart from anything else, it has held a certain popularity amongst those (like reactionary futurologist Jeremy Rifkin) who tell us that we live in an increasingly work-free society. It’s a pity, then, that few of these writers follow the logic of Marx’s argument in the Grundrisse to its conclusions. For while he indicates that capital does indeed seek ‘to reduce labour time to a minimum’, Marx also reminds us that capital is itself nothing other than accumulated labour time (abstract labour as value).23 In other words, capital is obliged by its very nature, and for as long as we are stuck with it, to pose ‘labour time … as sole measure and source of wealth.’

In its efforts to escape from labour, capital attempts a number of things that, each in their own way, fuel arguments that make labour time appear as irrelevant as the measure of capital’s development. Looked at more carefully, however, each can be seen in a somewhat different light. To begin with, capital tries as much as possible to externalise its labour costs: to take a banal example (although not so banal if you are a former bank employee), by encouraging online and teller machine banking and discouraging over-the-counter customer service. As for our own work regimes, many of us find ourselves bringing more and more work home (or on the train, or in the car). More and more of us also seem to be on stand-by, accessible through the net or by phone. Added together, such strategies (which, to add to the messiness of it all, may well intersect with our own individual aspirations for greater flexibility) go a long way to help explain that blurring of the line between the ‘work’ and ‘non work’ components of our day that Negri decries. On the other hand, they also cast that boundary in light other than that of the collapse of labour time as the measure of value, one in which – precisely because the quantity of labour time is crucial to capital’s existence – as much labour as possible comes to be performed in its unpaid form.

Secondly, in seeking to decrease labour costs within individual organisations, capital also reshapes the process through which profits are distributed on a sectoral and global scale. In a number of essays over the past 15 years, George Caffentzis has outlined the idea, first elaborated at some length in the third volume of Marx’s Capital, that average rates of profit suck surplus value from labour-intensive sectors towards those with much greater investment in fixed capital:

In order for there to be an average rate of profit throughout the capitalist system, branches of industry that employ very little labour but a lot of machinery must be able to have the right to call on the pool of value that high-labour, low-tech branches create. If there were no such branches or no such right, then the average rate of profit would be so low in the high-tech, low-labour industries that all investment would stop and the system would terminate. Consequently, ‘new enclosures’ in the countryside must accompany the rise of ‘automatic processes’ in industry, the computer requires the sweat shop, and the cyborg’s existence is premised on the slave.24

In this instance, if there appears to be no immediate correlation between the value of an individual commodity and the profit that it returns in the market, the answer may well be that there is none: the puzzle can only be solved by examining the sector as a whole, in a sweep that reaches far beyond the horizons of immaterial labour. Here too, it’s a matter of which parameters we choose to frame our enquiry.

Thirdly, and following on from above, the division of labour in many organisations, industries and firms has reached the point where it is difficult – and probably pointless – to determine the contribution of an individual employee to the mass of commodities that they help to produce.25 Again, this can foster the sense that the labour time involved in producing such commodities (whether tangible or not) is irrelevant to the value they contain. Marx, for his part, argued that the central question in making sense of all this was one of perspective:

If we consider the aggregate worker, i.e. if we take all the members comprising the workshop together, then we see that their combined activity results materially in an aggregate product which is at the same time a quantity of goods. And here it is quite immaterial whether the job of a particular worker, who is merely a limb of this aggregate worker, is at a greater or smaller distance from the actual manual labour.26

In this regard, Ursula Huws’ critique of notions of ‘the weightless economy’ deserves careful attention. Like Doug Henwood in his fierce deconstruction of the ‘new economy’,27 Huws draws our attention back not only to the massive infrastructure that underpins ‘the knowledge economy’, but also to ‘the fact that real people with real bodies have contributed real time to the development of these “weightless” commodities.’28 As for determining the contribution of human labour within the production of immaterial products, Huws argues, that while this might ‘be difficult to model, that ‘does not render the task impossible’. Or, in David Harvie’s words, ‘every day the personifications of capital – whether private or state – make judgements regarding value and its measure’ in their efforts ‘to reinforc[e] the connection between value and work’; He adds:

Hardt and Negri may believe in the ‘impossibility of power’s calculating and ordering production at a global level’, but ‘power’ hasn’t stopped trying and the ‘impossibility’ of its project derives directly from our own struggles against the reduction of life to measure.29

Other leads?

Not long ago, Dr Woo pointed me to a presentation by Brian Holmes entitled ‘Continental Drift Or, The Other Side of Neoliberal Globalisation’.30 In large part, his talk is a reflection upon the arguments in Hardt and Negri’s Empire, taking advantage of the hindsight provided by five years of events since the book’s publication. For Holmes, many of the arguments advanced in Empire were important for challenging commonplace assumptions about how to make sense of the ‘big picture’ of global power relations, forcing a reconsideration of terms such as globalisation and imperialism. But if the book helped in clearing away certain misconceptions, it has not been nearly so successful in supplanting them with more adequate ways of seeing.