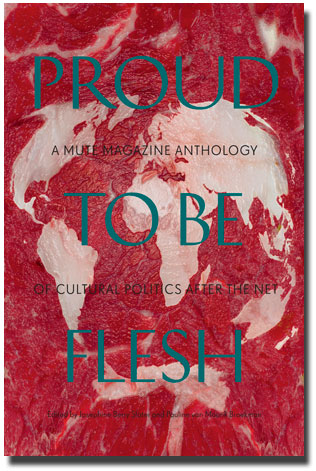

Chapter 7: Introduction - Under the Net: the City and the Camp

Introduction to Chapter 7 of Proud to be Flesh - Under the Net: the City and the Camp

—

Today it is not the city but the camp that is the fundamental biopolitical paradigm.

Giorgio Agamben

In the era of ‘free trade’ in commodities and the global flow of information, the control of people has never been stricter. It is in this sense that postmodernity’s much hyped ‘flows’ are rigidly denied to the majority of the world – left to eek out an existence in shacks and sewage – which has partly inspired Mute’s methodology, and that of this chapter. But, of course, it is not just the distance between the lives of the world’s underclass and this elite space of flows that we have analysed, but its proximity too. In other words, hyper-exploitation is not only to be found at the edges of the ‘First World’ but at its centres and, conversely, highly defended pools of privilege are threaded throughout the ‘Third World’. The articles in this chapter plot the ways in which the global proletariat and sub-proletariat are reconfigured, moved around and deployed against one another in a ceaseless attempt to drive down the cost of labour power and extract surplus value. Keeping this as its focus, the chapter develops an integrated understanding of localised ‘race riots’, the crisis of multiculturalism, urban regeneration, global slum clearance and migration.

As Angela Mitropoulos argues, in her article on the race riots in Australia’s Cronulla Beach (2005), wherever the social/wage contract risks breaking down, ‘the figure of the foreigner is put to work’. The ostensible fairness and symmetry of this contract, she explains, cannot be achieved without a border, a beyond, a ‘foreigner’. In order to be a citizen, it is necessary for there to be non-citizens; in order to maintain the ‘fair’ exchange of labour for wages amongst a working elite, the majority’s toil goes unremunerated or is paid a rate below the cost of their own reproduction. In his article on Chinese migrant labour in the UK, John Barker further elaborates this pitting of the working class against itself. Using J.A. Hobson’s discussion of the role of Chinese labour in his 1902 book, Imperialism, Barker exposes the historical necessity of cheap goods and cheap labour in placating the Western proletariat. A declining wage can be masked by the availability of cheap goods, while the import or use of cheap (Chinese) labour maintains a downward pressure on the wage generally. As a result, we see neo-slavery (of, say, gang-run cockle pickers at Morecambe Bay) underwriting the cheap goods sold to us in supermarkets.

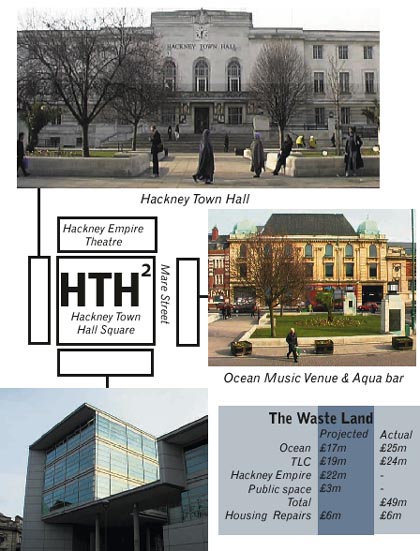

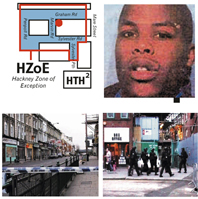

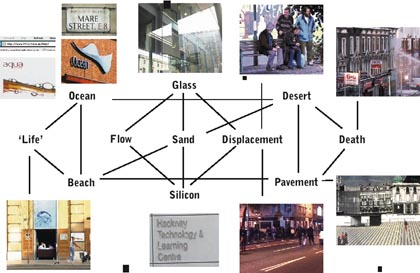

The Melancholic Troglodytes pick up on this dynamic, calling it ‘surreal subsumption’ – the co-existence of ‘real subsumption’ (a phase of capitalist development in which all of life becomes subject to exchange value) and ‘primitive accumulation’ (a stage in the transition to capitalism in which value is accumulated through theft or looting). The growth of slums is one manifestation of this surreal subsumption, their presence in many emerging ‘world cities’ serving to highlight the contradictions of a system in which the production of place-branded yuppie and tourist destinations is threatened by the stubborn presence of the surplus humanity with whose cheap labour the cities are (re)built. Amita Baviskar’s discussion of slum clearances in Delhi draws out the relationship between the cultural makeover of cities – in this case ahead of the Commonwealth Games Delhi will host in 2010 – and the working class blood-letting it entails. The London Particular’s photo-text collage, ‘Fear Death by Water’, sharpens this analysis, focusing on the twin strategies of cultural regeneration and new forms of class-cleansing population management in Hackney.

As London Particular member and Mute editor, Benedict Seymour, notes here, and in his article ‘Drowning by Numbers’ – on the disaster-movie scale of gentrification in post-Katrina New Orleans – renewal is a euphemism for ‘primitive accumulation’. While the value-producing industry of developed economies is gutted and production moved to wherever labour is cheapest, fictitious values are generated, partly through a series of commodity bubbles and partly through ever more complex financial instruments. The real estate bubble has played a crucial role in producing the fictitious values that obscure an underlying drop in wages. Gentrification, argues Seymour, works to inflate property prices and launch a ‘holistic attack on the wage’ through raising the cost of living and destroying the social resources which provide a means of support. In New Orleans, the disaster-propelled eviction of the black blue-collar majority and the influx of migrant, and often rightless, Latino labourers dispatched to rebuild the city, provides an extreme version of this ubiquitous process.

This example of capital’s deployment of racial conflict gives further justification to Matthew Hyland’s argument, made in his essay about the Bradford riots of 2001, that ‘A “race riot” […] is always a “class riot”’. Claims made by mainstream media over the apolitical nature of the riots between Asian and White British youths in a former British mill town, participate in a kind of psychologisation of racism which denies any consciousness of colonial history and the effects of globalised capitalism. This psychologisation and personalisation, Hyland argues, is behind the emptying of the original meaning of ‘institutional racism’ as the Black Panthers’ term for the systemic racism of the state is increasingly deployed to describe an anomalous defect embodied in certain individuals.

It is against this portrayal of the dispossessed as somehow bereft of politics that Richard Pithouse frames his account of resistance in the slums of Durban, South Africa. Banishing the cliché of the ‘global slum’, he insists on the particularity of the culture, infrastructure and politics of every slum. Against the representation of slums as vacuums of social organising and bereft of politics, Pithouse wields the example of Abahlali baseMjondolo – the Durban shack dwellers’ movement. This radically democratic organisation of shack dwellers combines thousands into a sustained fight against evictions and for basic amenities. It is not for the likes of Mike Davis or tenured leftists to accuse the global underclass of failing to fight global capitalism, argues Pithouse, when they are not fighting it on their own privileged terrain. To stand and fight where you are and over local pressures or depredations is always ‘a struggle to subordinate the social aspects of state to society’ and thereby weaken relations of local and global domination. The seemingly modest demand for the right not to be moved is one that unites struggles from the streets of Hackney to the slums of Durban; from this refusal to make way for the bulldozer of development come other refusals which hamper capital’s ruthlessly instrumental deployment of people. This chapter banishes any idea that the managed movement of peoples is about anything else.

Cheap Chinese

The perilous and exploitative employment of economic migrants, despite the public outcry against it, is an essential component of capitalist productivity. Concentrating on the structural insecurity of Chinese workers both in the UK and mainland China, John Barker moves from the contextless media coverage of specific deaths to the macroeconomic picture that caused them

In June of 2000, 58 Chinese people died of mass suffocation in the container of a lorry that arrived on a ferry at Dover. They died trying to enter the UK illegally. The direct cause of these deaths was the blocking of the container's air vents by the driver, a Dutchman called Perry Wacker. He is the worst of criminals; a panicker lacking the basic nerve required and, in this case, cutting the air supply for fear of being caught. The reporting of the case by large sections of the British media was either downright callous or sympathetic in abstract terms only, the horror felt from putting ourselves in the shoes of those who died proved to be too much.

In early February 2004, 19 Chinese workers who had entered the UK illegally died by drowning on the dangerous shoreline of Morecombe Bay, Lancashire sands rich in cockles. This time the reporting of what happened was more sympathetic. Once again the direct cause of their deaths was the reckless and incompetent greed of those employing them. It was reported that one of those who died, Guo Binlong, made a call on his mobile phone to his wife in the village of Zelang near Fuqing City not long before he drowned. He said, 'Maybe I'm going to die. It's a tiny mistake by my boss. He should have called us back an hour ago.'

Heartbreaking, twice over: the tiny mistake, that that's how Guo Binlong saw it, and the futility of the call. All the reporting implied that none of the 19 could read English or perhaps even speak it, and therefore would not have understood the sign up by the beach that said 'Fast rising tides and hidden channels. In emergency ring 999'. Perhaps if it had been read and understood, even as the danger became obvious, there would have been a reluctance to ring 999.

In another case involving a 40 year old Chinese man, Zhang Guo Hua, who entered the UK illegally and who died in Hartlepool after working a 24 hour shift in a plastics 'feeder' factory for Samsung, it was in no one's interests, as the reporter David Leigh put it, to make a fuss neither employers nor fellow workers. He was cremated without an inquest. And for Guo Binlong the mobile phone, one of the technological wonders of the present era of globalisation, that allowed a phone call from the darkness of Morecombe Bay, with the cold water rising, to a village in China, was useless to him. In contrast, a young female Londoner was happily saved from sinking mud on the shore of the Thames by using her phone.

The reporting of these deaths though more sympathetic, quickly identified the ruthless and criminal gangmasters as being responsible. Though they have remained largely unnamed the condemnation has been far stronger than in the case of Perry Wacker. The broadsheet papers talked of these gangsters using stolen 4-wheel drives in the same horrified tones that they portray loan sharks, as if the billions made by the 'high-street' banks belonged to a different moral universe. No, these gangsters were 'tough Scousers with torn jeans' and mixed in with them Triads and Snakeheads.

In the same period as these horrific deaths two other types of Chinese people in the UK are becoming important to its economy: students and tourists. All the students pay full overseas fees of £10,000, and in 2003 there were estimated to be 25,000 students making £250 million for British universities a fourfold increase in three years. In 2004, the estimate is of 35,000 students. The attractions for British universities is obvious. For the students it offers the chance of a university education when places are so limited in China, and when a British degree is said to look particularly good on CVs. What is certain is that the British government is not seeking to reduce their numbers, even when some also work in the black economy to help pay their way.

In October 2003, it was reported that the EU was expected to approve a new visa regime that will give Chinese people easier access to Europe. Chinese tour groups are expected to be given 'approved destination status'. This almost automatic visa granting would have an in-built safety clause from the EU's point of view in that Chinese tour operators would be heavily punished if any of their clients failed to return to China. This does not apply to the UK which is outside the Schengen Agreement but is equally keen to receive the money generated by such tourism. This is not negligible. Since 1998 the number of Chinese overseas travellers has almost doubled to 16.6 million. That is only a fraction of its 1.3 billion population, but the prediction is for 100 million overseas travellers by 2020, making them the world's biggest travellers. The UK does not want to be left behind but is seeking watertight agreements with the Chinese government to take back failed asylum seekers and issue new papers to those who deliberately destroy them, an issue the Blair government made much of after the Morecombe Bay horror.

These numbers, and prospective numbers, are another indication of the development of a middle-class in China; middle class in its consumption possibilities that is, or what might otherwise be called a nouveau riche. A copycat nouveau riche highlighted by the recent 'BMW case'. The wife of a rich property owner deliberately ran over the wife of a peasant, Liu Zhongxia, whose tractor she claimed, had scratched a wing mirror on her BMW in Harbin, Heliongjiang province, the heart of North East China's rust-belt, mimicking the Long Island heiress who recently maimed a few in similar fashion after a nightclub entry argument. The driver, Mrs Su, who had also paid someone to take her driving test, was acquitted as no witnesses dared to turn up. That such bad behaviour and the incomes and spending power that allow it now exist is hardly surprising given the dynamic growth of its industrial economy. It can be argued that it is only through the policies of the nationalist Communist Party, determined only to allow in Western capital on its own terms (however much that might be wishful thinking) that this growth has taken place. It is equally the case that it results from the shift of so much industrial production to China from the First World, to take advantage of a low wage workforce, one which is also producing this nouveau riche. The divisions of levels of income and possibilities in China are now so great that they might be called class divisions, and so obvious that the new Communist Party leadership of Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao have referred to it and of the need to narrow the gap between rich and poor. Beyond the never-ending campaign to root out the corruption of officials and their parasitic relation to the peasantry, this sounds like wishful thinking.

There are not going to be 1.3 billion Chinese in the 'middle-class' level global consumer class. What would they be producing? Even in the 'First World' it is a bogus promise. In the case of China, with such an across-the-board global consumer class, the global environmental crisis would be obvious even to those who do not wish to see it. Instead the situation as it is, and as it is developing, is eminently suitable to the global investor class and its transnational corporations and companies. As Oscar Romero puts it with the ruthless clarity of 'Third World' analysts, what matters to them is that 'national markets become increasingly liberalised so that they can seek the thin strata with high income in the underdeveloped countries ... they do not aim to sell to the entire population, it would be sufficient for 300 million in the upper-income brackets out of the total Chinese population to become their customers, though this may create a dangerous gap between the two Chinas.' (Oscar Romero, The Myth of Development, Zed Books). To manage this dangerous gap, what better than a highly sophisticated one-party state which can maintain a low-wage industrial assembly class, itself privileged from an even larger and lower-waged rural class. 300 million is enough, it dwarfs the present US market.

Taken with similarly proportioned figures in India, this development is a godsend to the global investor class which, as the SE Asian 'financial crisis' showed, was faced with a problem of global overproduction. A financial analyst also trading in snappy one-liners, Ed Yardeni, talked of the world needing all the yuppies it can get. Looked at in this light, the Chinese one-party system may be the more reliable given the stunning defeat of the BJP party in India in the recent election; a party which as Arundhati Roy described so well in her essay about the Gujarat pogrom, had sought to manage the 'dangerous gap' with a mixture of neoliberalism and Hindu nationalism. However chimerical the promises of the Congress Party might be, the election did allow the poor at least to say 'No' to the gap and the way it was being managed.

The poor of Britain and Europe know the present importance of China in particular, life would be that much harder without its prices: a pair of jeans for a fiver or toys for a quid. Its coming importance was highlighted 100 years ago in J A Hobson's Imperialism, a book unfairly famous only for having been used and misused by Lenin.

'China seems to offer a unique opportunity to the Western business man. A population ... endowed with an extraordinary capacity of steady labour, with great intelligence and ingenuity, inured to a low standard of material comfort ... Few Europeans even profess to know the Chinese ... the only important fact upon which there is universal agreement is that the Chinese of all the "lower races" are most adaptable to purposes of industrial exploitation, yielding the largest surplus product of labour in proportion to their cost of keep.'

Western ignorance seems to have changed little: the Sinology department at Durham University is scheduled to close, and the UK government is to withdraw the small support it gave to those doing M.Phils in Chinese.

Hobson was in no position to anticipate a Communist Revolution or the developing class system of the present. He did however foresee those fears of this industrial development getting out of Western control, manifested in notions of the 'yellow peril' which crop up throughout the 20th century to cause havoc in the minds of the leftist American writers Jack London and John dos Passos. 'It is at least conceivable that China might so turn the tables upon the Western industrial nations, and, either by adopting their capital and organisers or, as is more probable, by substituting her own, might flood their markets with her cheaper manufacturers, and refusing their imports in exchange might take her payment in liens upon their capital, reversing the earlier process of investment until she gradually obtained financial control over her quondam patrons and civilisers.' Such speculation belongs elsewhere: I don't know, for example, how much Chinese capital is invested in US Treasury bonds, but presumably it figures prominently in the thinking of professional, militarised Western geopolitics. In their considerations presumably, oil figures a great deal. China's 'industrial revolution' depends on it. Last year alone its oil consumption rose by 10 percent, along with what The Times (11/6/04) calls the 'rampant demand' from not just China, but India and Brazil too; countries 'continuing to guzzle world supply'. Guzzle! It may well be that the spread of US military bases across the oil-producing world is a product of those considerations.

At the same time Hobson raises another possibility, that 'the pressure of working class movements in politics and industry in the West can be met by a flood of China goods, so as to keep down wages ... it is conceivable that the powerful industrial and financial classes of the West, in order better to keep the economic and political mastery ... may insist upon the free importation of yellow labour for domestic and industrial service in the West. This is a weapon which they hold in reserve, should they need to use it in order to keep the populace in safe subjection.' Hobson himself had seen the use of Chinese labour in the South African gold mines. Although, to our ears he sounds melodramatic and unwarrantably sweeping, nevertheless his considerations do overlap with yet another round of the 'Immigration Debate'. The disparity between the freedom of mobility for capital and non-freedom for labour is mentioned, if at all, and then forgotten as if these really do represent parallel worlds. Instead, the same yes-andnos go round the carousel. Yes we need some skilled workers; yes, we must rationally look at future demographics and who will be needed to do the work to pay our pensions; but at the same time watch out for bogus refugees who are really economic migrants; watch out for the illegal immigrant. But not too hard.

After the death of three Kurdish workers on a level crossing on their way to pick spring onions in the East of England, it was suddenly discovered there were 2000 Chinese in Kings Lynn as if they had never been seen before. In Kings Lynn! Their deaths were more sordid in the banality of the accident than the thriller-like narrative of Romanian ex-train workers fixing signals so that other migrants could leap onto the Eurostar at obscure spots. The reality of the immigration debate is also more sordid. While the Third World is raided for trained nurses whose training was a cost to those countries, immigration fears are regularly rehearsed. The net result is that so many immigrants live in fear, and this fear is as functional to capitalist economies in the present era as it has been in the past. Migrant workers in Fortress Europe, and especially illegally-entered migrants, are far more likely to accept wages and conditions that are essential to its needs, and which in turn have a knock-on effect on wages and working conditions generally. Racist politicians and professional opinionists have their own grisly agenda, but these are functional to capitalist economies and their household names. The focus of these opinionists on 'failed' asylum seekers who are not allowed to work and, more recently, on a 'flood' of Roma and other Eastern Europeans who can work legally as EU citizens, gives the game away Their spotlight is not on Kings Lynn, a national blind spot. 'Policies that claim to exclude undocumented workers,' says Stephen Castle, 'may often really be about allowing them through side doors and back doors so that they can be readily exploited.' Or, as he put it some 30 years ago, commenting on the repatriation demands of Enoch Powell and other racist politicians: 'Paradoxically their value for capital lies in their very failure to achieve their declared aims.'

Inside Fortress Europe, for the UK in particular with its avowedly American-style deregulation, this process is all too visible. It is the dirty secret of the UK's economic success under New Labour. And they are proud of it, these shadow social democrats; the UK's official trade and investment website boasts of it. 'Total wage costs in the UK are among the lowest in Europe,' it says. 'In the UK employees are used to working hard for their employers. In 2001 the average hours worked a week was 45.1 for males and 40.7 for females. The EU average was 40.9. ... UK law does not oblige employers to provide a written employment contract. ... Recruitment costs in the UK is low. ... The law governing conduct of employment agencies is less restrictive in the UK. The UK has the lowest corporation tax of any major industrialised country.' Recently, Jack Straw has 'defied Europe' as the papers would have it. In a speech to the CBI, he promised that the UK would insist that the charter of fundamental rights created no 'new rights under national law, so as not to upset the balance of Britain's industrial relations policy', that is the one established by previous Conservative governments. In Britain there is nowhere for the exploited to turn and almost no employers are prosecuted for using illegal migrants.

To the extent that media coverage of the horror of Morecambe Bay went beyond fingering tough Scouser gangmasters in stolen 4-wheel drives, it focused on the power of supermarkets in the agricultural sector and their relation to those who do the harvesting a harvest which doesn't stop for a festival because the operation is non-stop, all year round. Migrant labour is up by 44 percent in the last seven years. Much of it is 'legal' via seasonal agricultural schemes, but of the 3-5000 'gangmasters' who organise this at least 1000 are illegal and give no protection to their workers. But then 'gangmasters' are in effect employment agencies and these, as New Labour like to boast, are the least restricted in the EU.

Despite Morecombe and the ensuing hand-wringing, nothing has changed. In September 2003 the House of Commons committee on the environment and food, chaired by Michael Jack MP, found that the agencies supposed to deal with 'illegal gangmasters' were making no real impact and set out the changes that would be needed. In mid-May 2004, a report by the same committee declared that the government had no clearer picture of the situation, and enforcement action against them had not increased. There had, it concluded, been 'no evidence of any change in the government's approach since last September. Indeed, in some respects, enforcement activity has diminished because of lack of resources.'

The beneficiaries of this, are the 'household' names of Tesco, Sainsbury and the rest, all profiting from this underclass. Andrew Simms describes a situation where 'Long chains of sub-contractors, commercial confidentiality and contractual obfuscation, allow household names to hide behind plausible denials ... we have evolved a system better at hiding, or distancing cause from effect.' This at a time when New Labour has never stopped talking of responsibilities in return for rights, exchange value-business. Those who died at Morecombe are believed to have moved on from Kings Lynn, in all likelihood taking a drop in pay from the vegetable picking rates of a market dominated by the 'high street' supermarkets.

The distancing of cause from consequence, the not-me-guv cry of the rich, the powerful and their portraitists, appear in all their colours in the Teeside Evening Gazette's report on a fire at the Woo One factory in the Sovereign Business Park, Hartlepool at the beginning of April this year. It mentioned the death of Zhang Guo Hua but only to emphasise that there was no proof of a connection between the haemorrhage that killed him and his working conditions. He had, it reported, been through the usual kind of work: cutting salads for Tesco suppliers in Sussex; fish-processing in Scotland; and packing flowers in Norfolk. Usual for whom?

The Queen had opened the nearby Samsung plant in 1996. It has a global turnover of $33 billion. When it opened the local MP, Peter Mandelson, wrote an article in praise of the company saying: 'some have the impression that the success of the tiger economies is based on sweatshop labour. This is a false picture.' The false picture is that sweatshop labour is exclusive to the 'tiger economies'. Zhang Guo Hua worked a 24-hour shift in Hartlepool. It was his decision of course, one can hear the not-me-guv voice saying. Woo One, the company Zhang Guo Hua worked for, was a 'feeder' factory for Samsung, its practices its own, as Samsung would have it. Zhang Guo Hua spent his last 24 hours stamping the word SAMSUNG onto plastic casings either for microwave oven doors or computer monitors, on his feet throughout. When he collapsed and went to hospital it was under another name. It was only when he was dead that a friend gave Zhang's real passport. So that even though he was cremated without an Inquest, it was in his own name.

An ex-worker at Woo One said that the minimum working week was 72 hours and the minimum shift 12 hours. Its managing director, Keith Boynton, agreed that English workers were not required to work these hours, but it wasn't him guv, the Chinese workers were technically employed by an outfit called Thames Oriental Manpower Management with offices in New Malden Surrey close to Samsung's corporate HQ. Thames Oriental Manpower Management a name that could only have been dreamt up by its proprietor a Mr Lin, not a tough Scouser in ripped jeans but a man who had been granted asylum claiming, claiming that is, that he was a North Korean refugee. Mr Boynton of Woo One said that 'What he (Mr Lin) pays the workers is up to him.' Mr Lin, it was reported had also taken control from Woo One of the nearby three-to-a-room set of dormitories and presumably, because he is now the villain, charged what he liked.

At this time Samsung boasted of record UK factory profits through 'unit cost reduction.' To get some idea of the process whereby this might happen, two pieces of Marx's structural economic analysis come to mind. He had for one thing deconstructed the notion of productivity long before the era of productivity deals. The very notion is one which exactly distances cause from consequence, or rather, and all the more modern for that, muddies the cause. 'Productivity' smears together: the productiveness of labour, that is the improved technology which allows for greater production; intensity of labour, which is how hard people work per hour (and here much of the improved technology simply increases the intensity of labour); and the length of the working day. These latter two factors are characteristic of 'primitive accumulation', and boy was that going on in Samsung's Hartlepool circus. Marx's misnamed Equalisation of Profit Law describes the mechanism whereby this works. The surplus or profit engendered by companies like Woo One, does not all go to them; the size of Samsung, the concentration of capital involved, and its power in relation to both its suppliers and marketing, means that it takes the lion's share of what has truly been accumulated in primitive fashion by small dependent suppliers. This is not some one-off phenomenon; one study shows Toyota having some 47,000 small firms working for it in a hierarchical structure, with most of those in the lowest layer passing the surpluses of 'primitive accumulation' up the chain to transnational corporations like Toyota who benefit from that mystery called 'value-added'.

When the story emerged in The Guardian (13/01/04), local MP Peter Mandelson said that he had 'written to Samsung about allegations made against Woo One in this tragic case.' The question is then, did he ever receive a reply because two days afterwards Samsung announced, out of the blue it was said, that it was closing the factory involved the Wynyard in Billingham. It blamed the high level of wages in NE England and said it was relocating to Slovakia where wages stood at £1 an hour. To which address did Mr Mandelson write? Was it passed on by a Post Office re-direction instruction. Has he received a reply? It seems unlikely given that Samsung's decision can hardly have been spur of the moment, or that a meeting with Woo One would have been a priority in the two days remaining. It transpired that Woo One themselves had already started to make its own move in the direction of Slovakia, and indeed announced some three weeks later that it was to close its computer casings plant in Hartlepool. On the news of Samsung's departure, Mr Mandelson, his letter still in the post somewhere, said that the price of their product had fallen worldwide, and that was 'the reason for its closure'. Prime Minister Tony Blair said he deeply regretted the loss of jobs involved but that 'It is part of the world economy we live in.'

There is of course much truth in what he says, but there is a complacency to that same voice which talks so much of our responsibilities that grates. If wages in Slovakia are £1 an hour, in China they are likely to be fifty pence, yet there is a need felt in the 'First World' to maintain low-cost mass production within its own frontiers even while its investor class shifts production to such countries. There is for one thing a structural limit to how many lawyers, journalists, IT specialists and bankers are required even in the First World, whatever might be said about education, education, education, while at the same time an increasing reluctance to cushion the circumstances of the excluded population. For another there is a fear at the psychic level of political economy that if so much industrial production is shifted to different parts of Asia, it will somehow weaken the West, be both sign and symptom of lazy decadence. More specifically than notions of decadence, there is a need for cheap labour in the First World, within its own frontiers, 'for it means that the South cannot extract monopoly rents for its cheap labour and bad working conditions' as Robert Biel puts it. There are sweatshops in London and Los Angeles even while automatic looms are capable of weaving 760 metres of denim per minute. As Hobson suggested, and the irony stands out in neon, this First World low-cost production requires migrant workers, workers made fearful by an unscrupulous media and political class.

Migrant workers are also essential to low-cost China and its 'economic miracle'. The numbers are hard to establish, 80 million is one estimate, 94 another, of recent migrants from the Chinese countryside, many of whom are also 'illegal'. Many Chinese cities require residency permits while it is these 'peasants' who do the jobs that Beijingers, for example, won't do themselves. And, just like anywhere else, for Albanians in Greece for example, they are accused of being thieves and dirty, while also exerting a downward pressure on local wages. Should there be a shrinkage of economic growth at a global level, these Chinese migrant workers will be the first to lose their jobs. For one thing 90 percent of them work without contracts, according to Li Jianfei, a law professor at the People's University. Even the state-run Trade Union estimates that they are owed over 100 million yen in back wages, but a campaign for repayment is for those with contracts only. Much of this is in the booming construction sector, where non-paying subcontractors blame large companies underpaying them, the Law of Equalisation of Profit in crude form.

In more classical form this law is also inherent in the condition of the coal mining industry. China's increasing oil dependence is well known, but it is also the world's largest coal producer. Chinese companies are making sizeable profits on legal and illegal mining operations, but at prices to industry which mean the real rates of profit of the consuming industries, often foreign-financed, are even greater. Exerting more pressure on the industry and its highly exploited workforce is central government's demand for more output. At the same time the industry has an appalling safety record; around 7000 miners were killed in 2003. There are promises of more inspectorates and the closing of illegal mines but, in the face of this 'energy crunch', this is likely to remain rhetorical. Safety investment is far less than the announced allocation. The grim reality is that with the retrenching of state-owned industries and the accompanying loss of benefits and pensions, the unemployed and the rural poor have entered the industry in huge numbers and are willing to work for cash in appalling and unsafe conditions, often assisting coal mine owners in avoiding safety procedures to ensure continued employment, as the China Labour Bulletin puts it. The death of one man in Hartlepool is hardly on the same scale, but the pressures for 'not making a fuss' are similar.

The wishful thinking of the new Communist Party leadership about reversing the dynamics of inequality looks like mere cynical rhetoric since it doesn't prevent it from maintaining a hard line against any independent worker protests over pay and conditions. A strike over pay at the part Taiwanese financed Xinxiong Shoe Factory in Dongguan city in April of this year resulted in several arrests. The Ferro-Alloy strike in Liaoyang province, involving 1600 workers, resulted in long prison sentences for Yao Fuxin and Xiao; meanwhile the workers are still without retrenchment compensation. In Hubei province, six workers have been arrested and are awaiting trial on charges of 'disturbing social order' after a peaceful demonstration at the Tieshu factory; this after 15 months of peaceful campaigning to recover more than 200 million Yuan in back wages, redundancy payments, workers shares and other moneys owed them by the bankrupt factory's management.

Other workers from the Tieshu factory have been sentenced to terms up to 21 months of 're-education through labour', a punishment which bypasses the criminal justice system. We do not know the extent of prison labour in China but it too is a component holding down general wages and conditions. There is nothing to get smug about, prison labour in the UK is being organised in a much more serious manner than before. The Woolworth's type chain in the North of England, Wilkinson's, is highly dependent on it for its products. A recent piece in The Economist (6/5/04) goes further, saying 'Hard-working immigrants transform the prison system'. It describes how Wormwood Scrubs (where a regime of extreme and racist staff violence is still being investigated) is full of cocaine drug mules from South America, and how the prison runs production lines for airline headsets and aluminium windows. The best jobs, it says, pay £25-40 a week 'depending on a prisoner's place on the ladder of privilege (as in all prisons, inmates are paid more for the same job if they behave themselves)'. It goes on to say that 'it is serious money for a third-worlder ... so a steady stream of remittances flows from Wormwood Scrubs to poor countries.' A grotesque conclusion might be that the poor victims of Morecombe Bay would have been better off there.

After the effective and international demonstrations against the World Trade Organisation in Seattle, the unity displayed there, the unity that was most unsettling to the global investor class, was quickly confronted with the sneers of professional opinionists. The many American trade unionists present, they said, had no global consciousness, they were just there to protect their jobs. Their demands for basic standards and rights for workers in the poor world were just a subtle form of protectionism, protecting their privileges. It is true that the Clinton administration would do almost anything to secure free trade deals in American interests, and also that Third World voices have been raised to say that such demands for minimum standards and conditions are aimed at cutting off the only way in which they can develop economically, that is with a monopoly on cheap labour, but it is reasonable to ask in return who and what these voices represent. The 'Third World' is not some homogeneous space and the class divisions in India and China are clear to see. Increasing inequality within countries rich and poor, is a global reality.

It is such a reality which gives us a nominally social-democratic and a nominally communist government, both spurning any effective protection of workers. Instead then, why not support those working for better wages, conditions and respect in China for example. Lawyers like Cho Li Tai and the Centre for Women's Law Studies and Legal Services at Beijing University; peasant activists like Li Changping; and most of all those imprisoned for demanding basic rights. For this to mean anything in the UK, a start would be mounting support for the Private Members Bill of Jim Sheridan MP and backed by the TGWU, for a thorough registration of 'gangmasters'. If it were to succeed it would at least remove one pillar of the government's boast of its cheap labour and lightly regulated employment agencies and go a step beyond cursory hand-wringing which was the extent of the response to the Morecombe tragedy. Six months later, in August, it was reported that rival 'gangs' of cockle-pickers had to be rescued from the same sands.

John Barker <harrier AT easynet.co.uk> was born in London and works as a book indexer. His prison memoir Bending the Bars was reviewed for Metamute by Stewart Home

Create Creative Clusters

The Creative London programme is a new city-wide scheme attempting to replicate the creativity-fuelled Shoreditch Effect across the capital's depressed boroughs as an economic cure-all. This latest bout of creative industry boosterism, argues David Panos, shows more signs of desperation than dynamism

At the end of April 2004, the London Development Agency (LDA), launched their new Creative London programme, a ten year ‘action plan’ aimed at ‘nurturing’ the creative industries in the capital. The LDA is one of nine regional bodies set up by New Labour to regenerate local economies and promote the interests of business. For them, ‘creative industries’ is an umbrella term that embraces everything from advertising, design, film, fashion, new media and architecture to opera, dance, music and art. The sector has been identified as the second biggest in London after finance and it is seen as the most significant potential growth area in the capital’s economy. Creative London draws on £500 million of public and private sector investment, rolling out a host of programmes such as the creation of venture capital funds for investment, promotional strategies for different trades such as design, fashion and film, legal advice on intellectual property rights as well as projects to re-brand and promote events like the Notting Hill Carnival and London Fashion Week. Over the course of a decade it aims to create 200 thousand new jobs and increase the ‘creative industries’’ annual turnover from £21 billion to £32 billion.

After the embarrassing ‘Cool Britannia’ posturing of the late 1990s and the fin-de-siecle hubris around the New Economy the idea that creativity is the great economic hope for the capital is far from new, but the relative sophistication of some of the LDA’s new plans to harness and ‘grow’ this sector is novel. Phenomena once considered marginal to the cycle of accumulation have become models for growth. Many of the strategies are designed to stimulate the overall ‘creative’ power of the capital, emphasising the importance of a ‘diverse ecology of small businesses’, ‘individual artists’ and ‘hobbyists’ to the development of the creative economy. Like so many ‘regeneration’ strategies, the emphasis is on tiny interventions to stimulate market forces rather than grand projects that might necessitate social spending.

One of the central initiatives of Creative London is the establishment of ‘Creative Hubs’ across the capital. Graham Hitchen, the LDA’s Head of Creative Industries, describes the process of building Creative Hubs as ‘identifying the areas where we think there is potential to really consolidate a cluster of activity that might have started to emerge and then dramatically growing that local economy through the creative business sector.’ This pre-emptive strategy intervenes into the development of such clusters by giving advice, creating partnerships, and outlining a ‘clear plan for growth’. Hubs would be administrated by partnerships of private bodies and arts or training organisations with a ‘track record in identifying creative talent’ and would form a cross-London network, sharing information and pooling strategies.

The precedents for these Creative Hubs can be seen in areas like Brick Lane and Shoreditch. It is a decade since they were colonised by artists, designers and small new media businesses, turning rundown old industrial hinterlands into the most fashionable districts in London. At the time local government and the regeneration industry were largely oblivious to this revalorisation process but today it seems it has been turned into an operating model. One council regeneration worker commented that ‘the LDA think that if they had been in control of what happened in Shoreditch it would have been bigger and happened faster’ and LDA strategy documents are already making rather far-fetched predictions about areas in South London becoming the ‘next Hoxton’. Other Creative Hubs are currently being proposed for areas as diverse as Deptford, Haringey, Ealing and Croydon.

The Creative Hub strategy promises to provide ‘more opportunities for all Londoners’ but Shoreditch’s transformation into a cultural node and night-time economy has had little positive impact on the ‘local’ (working class) residents in the surrounding area. Its actual effect has been to escalate property prices out of the reach of all but a privileged minority, and drive up the overall cost of living. Ironically, the LDA have also identified this tendency as a problem for business – according to their research one of the biggest concerns for creative startups is the soaring rents in central London. Creative London proposes to respond to this inflation by establishing a Creative Property Advice Service that negotiates with councils and developers to create rent caps and special leases that shield fledgling creative businesses from the very price hikes they stimulate. As the perceived ‘productive’ element in a local economy, the culture industry will get special privileges not meted out to less desirable inhabitants.

Creative London also builds on the existing tendencies to use artists as regenerating ‘urban pioneers’, attracting the upwardly mobile into formerly undesirable areas. One of the most innovative aspects of the program is the creation of a Creative Space Agency to act as a broker between artists and landlords whose property is vacant. Artists will be offered empty space across London on a rent-free basis to mount temporary shows or performances. Initially starting with property owned by the LDA and local councils, the plan is to extend the scheme to the private sector once it has been demonstrated to landlords that artists can act as free security guards whilst simultaneously rehabilitating a fallow property and increasing its value.

Of course, smart developers have been using artists and performers as part of their marketing strategies for some time, offering empty schools or warehouses for shows and performances before they are converted into live/work pads for yuppies. The Creative Space Agency formalises these ad hoc arrangements previously negotiated between artists and developers. Although it will undoubtedly make more space available, projects can be vetted, behaviour regulated, and the process brought under centralised control. Under the guise of making more ‘public space’ available the scheme puts more of the city back to work and by decreasing the number of empty buildings available it can be seen as a pre-emptive strike against squatting and other unregulated activities. Buildings are being offered to artists strictly on a project by project basis – use as a headquarters or residence will be forbidden and the LDA is already jumpy about the potential PR ‘downside’ of having to evict artists who decide to live for free. The Creative Space Agency makes clear art’s exceptional role in the new economy – it is notable that in a city full of vacant property there has been no comparable scheme developed for ‘uneconomic’ sections of society like community groups or the homeless.

Graham Hitchen points out that ‘the important thing about Creative London is that it is not led by an arts agency – we are an economic development agency saying this is economically important.’ Whilst the intervention of the LDA into arts policy is no doubt significant, Hitchen perpetuates a false opposition between the supposedly hardnosed world of economics and the ‘disinterested’ or indeterminate sphere of public arts. Arts agencies have been increasingly forced to justify their existence by proselytising culture’s economic function just as the theory that informs the LDA’s economic policy has become increasingly fixated on unquantifiable notions such as the role of networks and creativity. The theoretical roots of the program can be seen in the work of US theorists like Michel Porter and Richard Florida. Porter’s ideas about business clusters emphasise the importance of institutional support, collaboration, inter-business networking and shared infrastructure over old-style free market cost cutting and relocation, whilst Florida’s ‘Creativity Index’ cites factors like how many gay people or ‘bohemians’ live in a city as indicative of its long term economic potential.

The increasingly influential yet nebulous discourse about nurturing creative clusters and creative hubs is a desperate measure to shore up the economies of Western cities against the onslaught of globalisation. As they lose their remaining manufacturing base and more and more middle class service jobs migrate to Asia many have been forced to re-brand as ‘Cities of Ideas’. Provincial towns and ailing industrial quarters have little choice but to create the necessary conditions for an elite centre for ‘innovation’, wooing the ‘creative classes’ to rehabilitate their fortunes. Seen in this context Creative London is far from being a manifesto for dynamism. Rather it is a defensive strategy that seems unlikely to deliver much apart from increased precariousness for the majority of working Londoners.

Creative London http://www.creativelondon.org.uk/Creative Space Agency http://www.creativespaceagency.org.uk/The RIse of the Creative Class http://www.creativeclass.org/David Panos <david AT year-zero.com> is researching regeneration as part of The London Particular and plays in Antifamily and Asja auf Capri

Demolishing Delhi: World Class City in the Making

As London gentrifies its way toward the 2012 Olympics, social cleansing and riverine renewal proceed in parallel but more brutal form in Delhi. In preparation for the Commonwealth Games in 2010 the city's slum dwellers are being bulldozed out to make room for shopping malls and expensive real estate. Amita Baviskar reports on a tale of (more than) two cities and the slums they destroy to recreate

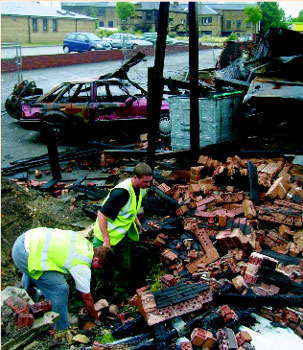

Banuwal Nagar was a dense cluster of about 1,500 homes, a closely-built beehive of brick and cement dwellings on a small square of land in north-west Delhi, India. Its residents were mostly masons, bricklayers and carpenters, labourers who came to the area in the early 1980s to build apartment blocks for middle-class families and stayed on. Women found work cleaning and cooking in the more affluent homes around them. Over time, as residents invested their savings into improving their homes, Banuwal Nagar acquired the settled look of a poor yet thriving community – it had shops and businesses; people rented out the upper floors of their houses to tenants. There were taps, toilets, and a neighbourhood temple. On the street in the afternoon, music blared from a radio, mechanics taking a break from repairing cycle-rickshaws smoked bidis and drank hot sweet tea, and children walked home from school. Many of the residents were members of the Nirman Mazdoor Panchayat Sangam (NMPS), a union of construction labourers, unusual for India where construction workers are largely unorganised.

Amita Baviskar In April 2006, Banuwal Nagar was demolished. There had been occasions in the past when eviction had been imminent, but somehow the threat had always passed. Local politicians provided patronage and protection in exchange for votes. Municipal officials could be persuaded to look the other way. The NMPS union would negotiate with the local administration. Squatters could even approach the courts and secure a temporary stay against eviction. Not this time. Eight bulldozers were driven up to the colony. Trucks arrived to take people away. With urgent haste, the residents of Banuwal Nagar tore down their own homes, trying to salvage as much as they could before the bulldozers razed everything to the ground. Iron rods, bricks, doors and window frames were dismantled. TV sets and sofas, pressure cookers and ceiling fans, were all bundled up. The sound of hammers and chisels, clouds of dust, filled the air. There was no time for despair, no time for sorrow, only a desperate rush to escape whole, to get out before the bulldozers.

But where would people go? About two-thirds of home-owners could prove that they had been in Delhi before 1998. They were taken to Bawana, a desolate wasteland on the outskirts of the city designated as a resettlement site. In June’s blazing heat, people shelter beneath makeshift roofs, without electricity or water. Children wander about aimlessly. Worst, for their parents, is the absence of work. There is no employment to be had in Bawana. Their old jobs are a three-hour commute away, too costly for most people to afford. Without work, families eat into their savings as they wait to be allotted plots of 12.5 sq. m. Those who need money urgently sell their entitlement to property brokers, many of them moonlighting government officials. Once, they might have squatted somewhere else in Delhi. Now, the crackdown on squatters makes that option impossible. They will probably leave the city.

One-third of home owners in Banuwal Nagar couldn’t marshal the documentary evidence of eligibility. Their homes were demolished and they got nothing at all. Those who rented rooms in the neighbourhood were also left to fend for themselves. One can visit Bawana and meet the people who were resettled, but the rest simply melted away. No one seems to know where they went. They left no trace. What was once Banuwal Nagar is now the site of a shopping mall, with construction in full swing. Middle-class people glance around approvingly as they drive past, just as they watched from their rooftops as the modest homes of workers were dismantled. The slum was a nuisance, they say. It was dirty, congested and dangerous. Now we’ll have clean roads and a nice place to shop.

Banuwal Nagar, Yamuna Pushta, Vikaspuri – every day another jhuggi basti (shanty settlement) in Delhi is demolished. Banuwal Nagar residents had it relatively easy; their union was able to intercede with the local administration and police and ensure that evictions occurred without physical violence. In other places, the police set fire to homes, beat up residents and prevented them from taking away their belongings before the fire and the bulldozers got to work. Young children have died in stampedes; adults have committed suicide from the shock and shame of losing everything they had. In 2000, more than three million people, a quarter of Delhi’s population, lived in 1160 jhuggi bastis scattered across town. In the last five years, about half of these have been demolished and the same fate awaits the rest. The majority of those evicted have not been resettled. Even among those entitled to resettlement, there are many who have got nothing. The government says it has no more land to give. Yet demolitions continue apace. Image: Demolition of Banuwal Nagar, 2006. Amita Baviskar The question of land lies squarely at the centre of the demolition drive. For decades, much of Delhi’s land was owned by the central government which parcelled out chunks for planned development. The plans were fundamentally flawed, with a total mismatch between spatial allocations and projections of population and economic growth. There was virtually no planned low-income housing, forcing poor workers and migrant labourers to squat on public lands. Ironic that it was Delhi’s Master Plan that gave birth to its evil twin: the city of slums. The policy of resettling these squatter bastis into ‘proper’ colonies – proper only because they were legal and not because they had improved living conditions, was fitfully followed and, over the years, most bastis acquired the patina of de facto legitimacy. Only during the Emergency (1975-77) when civil rights were suppressed by Indira Gandhi’s government, was there a concerted attempt to clear the bastis. The democratic backlash to the Emergency’s repressive regime meant that evictions were not politically feasible for the next two decades. However, while squatters were not forcibly evicted, they were not given secure tenure either. Ubiquitous yet illegal, the ambiguity of squatters’ status gave rise to a flourishing economy of votes, rents and bribes that exploited and maintained their vulnerability.

Image: Demolition of Banuwal Nagar, 2006. Amita Baviskar The question of land lies squarely at the centre of the demolition drive. For decades, much of Delhi’s land was owned by the central government which parcelled out chunks for planned development. The plans were fundamentally flawed, with a total mismatch between spatial allocations and projections of population and economic growth. There was virtually no planned low-income housing, forcing poor workers and migrant labourers to squat on public lands. Ironic that it was Delhi’s Master Plan that gave birth to its evil twin: the city of slums. The policy of resettling these squatter bastis into ‘proper’ colonies – proper only because they were legal and not because they had improved living conditions, was fitfully followed and, over the years, most bastis acquired the patina of de facto legitimacy. Only during the Emergency (1975-77) when civil rights were suppressed by Indira Gandhi’s government, was there a concerted attempt to clear the bastis. The democratic backlash to the Emergency’s repressive regime meant that evictions were not politically feasible for the next two decades. However, while squatters were not forcibly evicted, they were not given secure tenure either. Ubiquitous yet illegal, the ambiguity of squatters’ status gave rise to a flourishing economy of votes, rents and bribes that exploited and maintained their vulnerability.

In 1990, economic liberalisation hit India. Centrally planned land management was replaced by the neoliberal mantra of public-private partnership. In the case of Delhi, this translated into the government selling land acquired for ‘public purpose’ to private developers. With huge profits to be made from commercial development, the real estate market is booming. The land that squatters occupy now commands a premium. These are the new enclosures: what were once unclaimed spaces, vacant plots of land along railway tracks and by the Yamuna river that were settled and made habitable by squatters, are now ripe for redevelopment. Liminal lands that the urban poor could live on have now been incorporated into the profit economy.

The Yamuna riverfront was the locale for some of the most vicious evictions in 2004 and again in 2006. Tens of thousands of families were forcibly removed, the bulldozers advancing at midday when most people were at work, leaving infants and young children at home. The cleared river embankment is now to be the object of London Thames-style makeover, with parks and promenades, shopping malls and sports stadiums, concert halls and corporate offices. The project finds favour with Delhi’s upper classes who dream of living in a ‘world-class’ city modelled after Singapore and Shanghai. The river is filthy. As it flows through Delhi, all the freshwater is taken out for drinking and replaced with untreated sewage and industrial effluent. Efforts to clean up the Yamuna have mainly taken the form of removing the poor who live along its banks. The river remains filthy, a sluggish stream of sewage for most of the year. It is an unlikely site for world-class aspirations, yet this is where the facilities for the next Commonwealth Games in 2010 are being built.

For the visionaries of the world-class city, the Commonwealth Games are just the beginning. The Asian Games and even the Olympics may follow if Delhi is redeveloped as a tourist destination, a magnet for international conventions and sports events. However wildly optimistic these ambitions and shaky their foundations, they fit perfectly with the self-image of India’s newly-confident consuming classes. The chief beneficiaries of economic liberalisation, bourgeois citizens want a city that matches their aspirations for gracious living. The good life is embodied in Singapore-style round-the-clock shopping and eating, in a climate-controlled and police-surveilled environment. This city-in-the-making has no place for the poor, regarded as the prime source of urban pollution and crime. Behind this economy of appearances lie mega-transfers of land and capital and labour; workers who make the city possible are banished out of sight. New apartheid-style segregation is fast becoming the norm.

The apartheid analogy is no exaggeration. Spatial segregation is produced as much by policies that treat the poor as second-class citizens, as by the newly-instituted market in real estate which has driven housing out of their reach. The Supreme Court of India has taken the lead in the process of selective disenfranchisement. Judges have remarked that the poor have no right to housing: resettling a squatter is like rewarding a pickpocket. By ignoring the absence of low-income housing, the judiciary has criminalised the very presence of the poor in the city. Evictions are justified as being in the public interest, as if the public does not include the poor and as if issues of shelter and livelihood are not public concerns. The courts have not only brushed aside representations from basti-dwellers, they have also penalised government officials for failing to demolish fast enough. In early 2006, the courts widened the scope of judicial activism to target illegal commercial construction and violations of building codes in affluent residential neighbourhoods too. But such was the outcry from all political parties that the government quickly passed a law to neutralise these court orders. However, the homes of the poor continue to be demolished while the government shrugs helplessly.

Despite their numbers, Delhi’s poor don’t make a dent in the city’s politics. The absence of a collective identity or voice is in part the outcome of state strategies of regulating the poor. Having a cut-off date that determines who is eligible for resettlement is a highly effective technique for dividing the poor. Those who stand to gain a plot of land are loath to jeopardise their chances by resisting eviction. Tiny and distant though it is, this plot offers a secure foothold in the city. Those eligible for resettlement part ways from their neighbours and fellow-residents, cleaving communities into two. Many squatters in Delhi are also disenfranchised by ethnic and religious discrimination. Migrants from the eastern states of Bihar and Bengal, Muslims in particular, are told to go back to where they came from. Racial profiling as part of the war on terror has also become popular in Delhi. In the last decade, the spectre of Muslim terrorist infiltrators from Bangladesh has become a potent weapon to harass Bengali-speaking Muslim migrants in the city. Above all, sedentarist metaphysics are at work, such that all poor migrants are seen as forever people out of place: Delhi is being overrun by ‘these people’; why don’t they go back to where they belong? Apocalyptic visions of urban anarchy and collapse are ranged alongside dreams of gleaming towers, clean streets and fast-moving cars. Utopia and dystopia merge to propose a future where the poor have no place in the city.

Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata and many other Indian cities figure prominently in what Mike Davis describes as a ‘planet of slums’. Slum clearances may give India’s capital the appearance of a ‘clean and green Delhi’ but environmental activism has simply shifted the problem elsewhere. The poor live under worse conditions, denied work and shelter, struggling against greater insecurity and uncertainty. Is Davis right? Has the late-capitalist triage of humanity already taken place? Even as demolitions go on around me, I believe that Davis might be wrong in this case. Bourgeois Delhi’s dreams of urban cleansing are fragile; ultimately they will collapse under the weight of their hubris. The city still needs the poor; it needs their labour, enterprise and ingenuity. The vegetable vendor and the rickshaw puller, the cook and the carpenter cannot be banished forever. If the urban centre is deprived of their presence, the centre itself will have to shift. The outskirts of Delhi, and the National Capital Region of which it is part, continue to witness phenomenal growth in the service economy and in sectors like construction. Older resettlement colonies already house thriving home-based industry. The city has grown to encompass these outlying areas so that they are no longer on the spatial or social periphery. This longer-term prospect offers little comfort to those who sleep hungry tonight because they couldn’t find work. Yet, in their minds, the promise of cities as places to find freedom and prosperity persists. In those dreams lies hope.

Amita Baviskar <baviskar1 AT vsnl.com> researches the cultural politics of environment and development. She is the author of In the Belly of the River: Tribal Conflicts over Development in the Narmada Valley and has edited Waterlines: The Penguin Book of River Writings. She is currently writing about bourgeois environmentalism and spatial restructuring in the context of economic liberalisation in Delhi

Disrespecting Multifundamentalism

The term ‘respect!’ has gone from rude boy subcultural slang to reactionary Third Way spin, from grassroots contestation of power, to tool for disciplining the new dangerous classes. Melancholic Troglodytes offer a critical genealogy of the strategies used by proletarians to challenge bourgeois dignity and respectability and call for some new (use) values of our own

‘Give respect, get respect!’ – British government’s action plan

It is essential to understand at the outset that Tony Blair’s latest moral crusade based on returning respectability to cities and villages is not a gimmick or a quick fix but part and parcel of a protracted attack on the working class.

The aim of this text is twofold: first, to analyse the nature of this attack by showing the antagonism between bourgeois respectability and proletarian respect; and second, to demonstrate how this conflict is related to the demise of two of capital’s most pernicious ideologies – that of religious fundamentalism and secular multiculturalism.

Perhaps understandably, some readers may baulk at our contention that the journalistic inanity known as (eastern) fundamentalism and its flip side of (western) multiculturalism are in crisis. After all, are we not subjected in the media to a daily barrage of mullah-morons self-righteously preaching the finer points of Shari’a law? Do we then not have to endure the gormless liberal multiculturalist paternalistically tut-tutting his uncivilised interlocutors? Has not Hamas secured a major victory for fundamentalism in Palestine? Is not religion calling the shots in Iraq? Is there not sufficient evidence that the world has gone completely insane? Should we not adopt a bunker mentality and hide until this tempestuous madness has run its course? By tracing the vicissitudes of the notion of respect we hope to offer a more nuanced – as well as optimistic – assessment of the current state of class struggle.

‘Is there no respect of place, persons, nor time, in you?’ William Shakespeare Twelfth Night

Class society has always made use of both ideology (Marx) and discursive practice (Foucault) in order to secure the status quo. These mechanisms of regulation have in turn relied on nodal values through which respectability has been policed. These nodal values exist in a chain of signification and the study of their evolution can be instructive.

During what is lazily referred to as pre-modernity (more accurately slavery, serfdom, feudalism, etc.) the nodal value greasing the wheels of society was honour. The gladiator in ancient Rome, the crusader during the Middle Ages and the knight during feudalism accrued honour through a mixture of courage, skill and sacrifice. Their lower class counterparts – the slave, the serf and the peasant – remained in a permanent state of shame.[1] Only occasionally could a lower class person wipe away the shame associated with their social status and gain honour. This required a superhuman endeavour. Spartacus stands as an archetypal example of such a move. Outside this cosy polarity between shame and honour, respect began to make a tentative appearance amongst the populace. Artisans and craftsmen who managed to monopolise certain trades began to be granted a grudging respect by the aristocratic elite.

From the 17th century onwards, with the gradual advent of the formal phase of capitalist domination, absolute surplus value extraction became the norm in many industries. Exchange value was characterised by the regulation of punctuality, sexuality and discipline. The nodal value that became associated with this phase was dignity, which implied that identity is independent of birth, institutional roles and hierarchy. The Dutch national liberation movement of 1579-1581, the English Revolution of 1640-60 and the French Revolution of 1789 represent a series of historical ruptures which transformed society’s nodal value from honour to dignity.

To turn up at work punctually, engage in the production process conscientiously, look and sound orderly and discharge one’s sexual duties spartanly (in other words to be a good citizen) were characteristics of dignity. By default, remaining unemployed, dirty and promiscuous became a sign of undignified behaviour, punishable by poverty and stigmatisation. The English Ranters were an early victim of bourgeois indignation. Naturally most radicals have been deeply suspicious of dignity. F. Palinorc has dismissed it as a shibboleth of bourgeois thought:

[Dignity is an] absurd, utopian cry under a system of total value domination, analogous to the battle cries of democracy and liberty.[2]

Later we will attempt to show how the situation is somewhat more complicated, but for the time being let us pursue the historical development of capital further.

Those societies that have negotiated the passage from formal to real domination have experienced a more flexible form of surplus value extraction and a greater disparity between the private and public spheres of human behaviour. Also, in this phase, workers begin to enter the economy as consumers of leisure and the bourgeoisie is keen to control leisure’s ‘moral misuse’. Dignity began to display its limitations and was gradually marginalised by a more sought after nodal attribute – authenticity. This is an individualised attribute which encourages political engagement based on the notion of identity. The ability to be oneself in public now becomes an ideal only available to a handful of clowns, method actors and ‘mad’ individuals who require neither dignity nor honour since they know no shame. The rest of us are reduced to purchasing tourist-authenticity in far off, ‘uncontaminated’ lands in the form of Nicaraguan coffee, Turkish whirling dervishes and the occasional divine miracle.

This historical chain of signification (honour – dignity – authenticity) is roughly aligned with pre-capitalism, formal capital domination and real capital domination. However, this schematic association breaks down on closer inspection. Raymond Williams, for instance, talks of three types of cultural artifacts: the dominant, the residual and the emergent.[3] All three usually co-exist in any one period of development. For instance, the dominant cultural node in contemporary India is dignity which corresponds to the formal phase of capital domination. But India is a complex society which also evolves around residual cultural artifacts like honour and emergent ones such as authenticity. Most Indians require a mixture of honour-dignity-authenticity for obtaining respectability but depending on their specific cultural-economic status, they prioritise this chain of signification differently. But, and here is the key question for us, what happens if you are a caste member who is denied access to this chain of signification? In other words, what if you are not considered a full citizen with a delineated set of rights and duties? How do you then seek self-worth and social status as a prelude for interaction with the rest of society?

‘Unthinking respect for authority is the greatest enemy of truth.’ Albert Einstein

The proletariat has historically employed three main strategies for overcoming the problems cited above. These three strategies correspond to varying degrees of proletarian empowerment:

1. Re-accentuation of respectability

The first strategy re-accentuates the meaning of nodal values when the proletariat does not feel strong enough to reject them (Bakhtin). For example, in the 1960s US ‘blacks’ defined dignity according to class markers. Bourgeois blacks, such as Martin Luther King, understood dignity to mean upright citizenship and demanded equal employment and educational opportunities. Under their scheme black dignity was to be guaranteed by enlightened leaders and enshrined in the law. The law may not be able to police racist prejudice but its admirers believe it is capable of changing discriminatory behaviour and that this in time might lead to cognitive alterations.

Other blacks, such as the Black Panthers, were also seeking reforms although in their case extra-legal actions were used in order to pressurise legislatures. Black Panthers understood dignity as full citizenship and since blacks were only considered three-fifth citizens, the strategy aimed to obtain the remaining two-fifths of rights denied them by the Constitution. Meanwhile, black welfarism would restore dignity to black lumpenproletarians left out of the circuits of capital accumulation.

Lastly, proletarian blacks had a simpler and more radical conception of dignity which was shaped by their everyday confrontation with racism. Proletarian dignity confronted both racist behaviour (e.g. discrimination in the shape of Jim Crow laws or segregation) and racist attitude (e.g. personal prejudice). The stable dictionary ‘meaning’ of the term, dignity, remained the same but the personal ‘sense’ in which it was employed had shifted dramatically (Vygotsky). Proletarian dignity, therefore, cannot simply be ignored or dismissed as bourgeois. It must be understood in its concrete context and as part of a dialectical supercession of all values.

It is essential to understand that proletarian demands for dignity, whether expressed by black American workers in the 1960s, Russian workers in 1905 or Palestinian workers crossing Israeli check-points are not a static entity, for they can fast evolve in one of two directions. Dignity can either solidify into reactionary pride or evolve into proletarian respect. Examples of the former include the notion of black pride promoted by fascists such as Farrakhan’s Nation of Islam, Ahmadi-Nezhad’s Iranian brand of Strasserism or perhaps even the BNP’s opportunistic slogan of ‘rights for whites’.[4] Examples of the latter include the solidarity amongst British black proletarians during the 1970s and 1980s centred on respect. A similar phenomenon was witnessed amongst Native Americans in the 1970s during their struggle for land and an end to poverty, or during the first Palestinian Intifada when fighting both the Israeli army and Palestinian leaders simultaneously generated mutual respect within and between refugee camps.

2. Collective rejection of respectability

There are occasions when due to strength or sheer desperation, we manage to go beyond mere re-accentuation of bourgeois respectability and a deep seated rejection sets in. A minority faction within the anti-war movement in the run up to the war on Iraq achieved this in some measure (the rest, be they secularist or religious, remained within the bounds of bourgeois respectability). The honour and glory of war was rejected sometimes through rational arguments and sometimes through collective laughter and irony; the dignity of anti-Saddam victims who were opportunistically paraded in the media was exposed as a propaganda ruse and nullified. The authenticity of evidence put before us to justify the war was also queried at every turn. Some further examples of rejection of respectability may concretise the point: during a one-minute silence in a demo against the First Gulf War, bourgeois respectability was compromised when a group of radicals insisted on shouting, ‘No War but the Class War’; at the beginning of the Second Gulf War an American protestor whose husband was killed in Vietnam said, ‘I learned the hard way there is no glory in a folded flag.’ Similarly, a sizeable minority of Iranian proletarians have rejected the concept of martyrdom and warfare as a route to heaven as is evident in the struggle against the burial of the ‘unknown soldier’ within university campus grounds. ‘Queer carnivalesque’ would be another instance where we have witnessed a break with heteronormative notions of sexual respectability as well as gay/lesbian essentialism.

Proletarian resistance creates a gap between reality and official ideology. This gap has to be filled by rhetoric. The further decomposition of the art of rhetoric in the speeches of Bush, Blair, the Pope, Ahmadi-Nezhad and Bin Laden is itself an indication that the chain of signification is losing its shine everywhere. The first canon of classical rhetoric as practised in ancient Greece was ‘invention’. With the demise of the Sophists, invention was eclipsed by one or more of the other divisions, namely; ‘arrangement’, ‘style’, ‘memory’ and ‘delivery’. Today’s politicians have conveniently dispensed with memory and delivery, leaving arrangement and style as the only two vehicles for rhetorical discourse.

There are also moments of desperation which lead to a frontal assault on bourgeois respectability. Refugees and asylum seekers who are being forcefully removed have been known to go on hunger strike or strip to their underwear at airports as a final act of defiance against immigration authorities. Here, respectability which works through raising the threshold of shame (Goffman) is marginalised by the grotesque collective body (Bakhtin). Similarly, prison revolts undermine in a matter of hours the systematic work of chaplains, social workers and prison staff whose programme is to instil prisoners with etiquette and dignity.

3. Creation of new concepts like respect for by-passing respectability

When the balance of class forces is in our favour and we have the luxury of time and space, use value may temporarily eclipse exchange value. These preconditions not only make possible a rejection of bourgeois respectability but also foster proletarian respect. Moments of social rupture are usually preceded by a preponderance of mutual respect amongst the proletariat. This is not simply a case of positing our morality against theirs as Trotsky would suggest. Rather it is a case of rejecting exchange value and morality as the regulator of the private-public split in favour of a qualitatively different form of immeasurable value based on human need and solidarity. For instance, the term ‘respect’ finds its origins in Jamaica as part of the ‘rude boy’ slang subculture and is transported to Britain where it is picked up by the ‘white’ working class.

‘Nothing is more despicable than respect based on fear.’ Albert Camus

So far, we have postulated that respect is foregrounded among those sections of the proletariat traditionally denied access to the rulers’ chain of signification. We have also suggested that its appearance is a sign of proletarian strength since it is generated from below.