Chapter 6: Introduction - Assuming the Position: Art and/Against Business

Introduction to Chapter 6 of Proud to be Flesh - Assuming the Position: Art and/Against Business

—

I want to burn down all your factories!

Gustav Metzger

The last thing we should be doing is embracing our miserable marginality.

Bifo

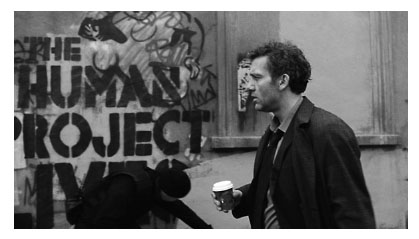

The title of this chapter hopefully conveys a sense of the dangers involved in mirroring the corporate ‘other’ by self-understood radicals. As the slogan on a badge produced by the artists’ collective, Inventory, has it: ‘Ironic mimesis is not critique, it is the mentality of a slave!’ This formula’s vitriol no doubt derives from over-exposure to at least a decade’s worth of ‘adbusting’ and ‘culture jamming’. Such strategies, argues Neil Mulholland in his article on the cultural logic of Ambient, amount to little more than an attempt at ethical capitalism. But, if adbusting is now widely understood to be a kind of ‘anti-corporate corporatism’, are all mimetic strategies deployed by the postmodern and post-web generation to be so summarily dismissed? Mute’s coverage of ‘political net.art’ and electronic civil disobedience, especially during the latter half of the ’90s, reveals a thinking around the mimicry of capitalism’s modalities that goes beyond mere liberal reformism or radical chic. This chapter deals with the self-mirroring transformations of business and culture within digitally networked globalisation, and compiles the arguments for and against imitating the veneer, if not logic, of corporate activity within networked capitalism.

The interview with Artist Placement Group co-founders, Barbara Steveni and John Latham, by myself and Pauline van Mourik Broekman, uncovers some of the early moves in the courtship between art and business in the mid-1960s. In step with a contemporary desire to spin the modes and materials of industrial capitalism in new directions, this UK-based group of conceptual artists, negotiated industrial placements for artists. This project, the aim of which was to throw a creative catalyst into the heart of commercial production, created some very divergent results. Gustav Metzger drove a captain of industry out of the APG-convened Industrial Negative conference by declaring, ‘I want to burn down all your factories!’ Meanwhile, in the 2002 interview, Steveni reveals her more conciliatory position by describing companies as ‘conglomerates of individuals’ open to influence. Capitalism, this suggests, could be reformed by converting key players at the top of the tree, not by violent proletarian struggle from beneath. While some of its members engaged in class-based politics, APG could certainly be accused of pre-empting today’s neoliberal ‘culture industry’ and alliance culture.

Neil Mulholland’s above-mentioned critique traces the trajectory of culture’s assimilation into commerce to its suffocating terminus. Amongst a wide array of things ambient, he discusses the work of Glasgow-based artists David Shrigley, Ross Sinclair and Jonathan Monk. These artists, working in the cash strapped, post-recession ’90s, used nonchalant, witty and minimal strategies for ‘interrupting the equilibrium and continuity of temporal space’. These low-budget means of ‘re-narrating’ the city were ‘gradually disassociated’ from art and academia to become, by the end of the decade, the tools of viral advertising and ‘ambicommerce’.

Reviewing the ICA’s CRASH! Corporatism and Complicity show of 1999, however, Benedict Seymour questions the implied obligation for art to perform a critical function. While the show’s curators and many of its artists struggled to thwart the paradigm of ironic mimesis, or complexify it beyond the point of simple co-optability, Seymour suggests that less self-flagellation and more ‘being in uncertainty’, even luxuriant escapism, may be what’s required.

While Seymour speculates that the solution to the riddle of contemporary cultural politics is, perhaps, a rejection of art’s ethical responsibility, interviews with Critical Art Ensemble (CAE) and Electronic Disturbance Theatre’s (EDT) Ricardo Dominguez strike a very different note. Rejecting the efficacy of representative democracy and, in CAE’s case, the attendant forms of street-based protest bar highly localised ones, they advocate a proliferation of anarchist-style cells working across the internet to thwart the smooth functioning of power. This electronic civil disobedience should be as nomadic and distributed as its state-corporate target. Rather than accepting the ‘voyeuristic’ and ‘narcissistic’ relationship to virtual space prescribed by the military-industrial complex, EDT advocate that participants in net culture assume an ethical stance vis-à-vis a ‘distant other’. Both groups have pursued a ‘marriage of convenience’ between activists and hackers to disrupt techno-capitalism and hit it where it hurts – its databases.

In their ‘Culture Clubs’ article, Anthony Davies and Simon Ford formulate a similar response to the flattened networks and hollowed-out companies that characterised the commercial landscape of the ’90s, and continue to do so. As outsourcing and flexibilisation become the order of the day for business, cultural organisations followed suit, and these hollowed out institutions, part-funded through corporate sponsorship (rather than patronage), were increasingly made available to commercial agendas. As faith in the culture industry peaked with New Labour and the newly desirable arts were understood as the ‘secret weapon of business’, any residual idea of art’s autonomy beyond the sphere of commerce perished.

But if, in response, adopting the virtual and nomadic forms of capital seemed to be justified by the successes of the anti-globalisation movement of the late-’90s and early-’00s, its cultural variant was arguably less successful. In his text, ‘Learning the Right Lessons’, which revisits the politics of ‘tactical media’ ten years on, David Garcia quotes Bifo’s denunciation of the Telestreets movement at a 2004 meeting in Senigallia. While representatives from the micro-broadcasting movement met in an obscure Italian seaside town, Berlusconi’s government passed the Gasparri law, consolidating his grip on the Italian mediascape. Bifo and others berated the Telestreets producers for embracing their ‘miserable marginality’ and consequently missing the opportunity to attack the legislation head-on. The diffusion of efforts and effects, amidst loosely allied producers, despite being a celebrated tactic for subverting networked capitalism, risks evaporating altogether. As with the alliance culture of the business sector, such loose ties of commitment and intention can produce as much instability as contingent support. The mimesis of capital’s modus operandi by radical groups and artists, though not necessarily displaying the mentality of the slave, is liable to the same turbulence and collapse that its markets are currently experiencing. In the multimedia age, if a return to the politics of what Baudrillard called ‘the system of meaning and representation’ is no longer an option, what forms of collaboration will develop within, and against, capitalism’s nomadic networks? And, whatever happened to the strategy of burning down its factories?

Do As They Do, Not As They Do

All work and all play make Toywar soldiers' day! Josephine Berry on etoy and eToys' legal tussle in the symbolic economy.

Last November 29th, US online toy retailer eToys brought a suit against the European net art collective etoy, blocking them from using their own domain name www.etoy.com — registered two years before eToys even existed — in a clear cut case of corporate might and spite, not to mention greed. The closeness of ‘etoy.com’ to the retailer’s own URL www.etoys.com, argued every kiddy’s favourite corporation, was confusing customers who also risked being exposed to pornographic and violent (a.k.a. European and arty) content. eToys played heavily on the family values card to secure a preliminary US court ruling in their favour. Not surprisingly, this action elicited torrents of vitriol from etoy fans and the Reclaim the Domain Name System lobby alike. Quite a lot more surprising, however, given the hotness of the DNS topic right now, was the professionalism and commitment accomplished by Toywar — etoy’s name for its resistance campaign and website www.toywar.com — whose antics finally secured eToys’s total climb down as they watched their shares plunge by 70rom $67 to $20 a share. In what has been described as "the Brent-Spar of e-commerce", eToys dropped the case ‘without prejudice’ on January 25th (i.e. withholding the option to resume proceedings again) and agreed to pay etoy’s court costs of $40,000. There is no doubt that this has been a landmark victory in the crucial battle over Domain Names and an inspiringly unorthodox example of ‘dispute resolution’.

But hold on, did I say ‘professionalism’ and ‘commitment’ just now? Wouldn’t those words look more at home in a go-gettin’ corporate presentation? Precisely the trick. etoy was itself, as Douglas Rushkoff recently put it, intended "both as a satire of the corporate value system and a barometer of the information space." If power is corporate and global, argue etoy, then art should be too. The etoy campaign is replete with both metaphors and strategies lifted straight out of the corporate world. Potential recruits are incited to "HELP US PROTECT THE etoy.BRAND AND BECOME A SHAREHOLDER!". Partisan efforts are rewarded with loyalty points corresponding to ‘etoy.SHARES’ in the ‘etoy.ART-BRAND’. In a press release their spokesman, Zai, informs us that "investors keep etoy alive. They invest into the future of Internet art." Indeed, US based activist art group RTMark’s decision to award etoy ‘sabotage project funding’ could effectively be seen in terms of a joint venture. Not only are individual art groups adopting the walk and talk of the corporate world, but they’re even corporatising amongst themselves; sharing resources and databases, and piggybacking on each another’s brand value.

Could it be that etoy’s use of shares and markets effectively extends the modernist game of turning the conditions of the artwork’s making into the subject of the artwork itself (e.g. turning the canvas into the subject of the work) to the immaterial realm of financial markets? In other words, is the market really becoming more than just the subject of the art? Is it becoming subject and support (of the signifier) in one? Is an etoy.SHARE an actual share and its metaphor at the same time? Before ‘speculating’ on this any further, it should be mentioned that the role played by the Toywar in the free-fall of eToy’s shares is greatly contested. The FT’s view is reassuringly prosaic, blaming eToy’s humpty-dumpty antics on "the cost of tripling its customer base over the christmas holidays" amongst other things.

Etoy’s own line on the status of their share system masquerades behind an equally neutralising and predictable language: that of art history. Commenting on the possible illegality (within the US legal system) of issuing ‘etoy.SHARES’, they neatly side-step the whole modernist trajectory mentioned above. Insisting on the docility of the signified, they claim: "we never sold a share to a person who did not know that this is an ‘ART INVESTMENT’ ... according to international lawyers and advisors the word ‘share’ is not limited or registered for the use in financial markets! If artists can call art products ‘landscape XY’, ‘naked body blabla’ or ‘the death’ …we insist on the right to call our work etoy.SHARE... because value systems, stock markets and the surreal etoy.CORPORATION are our TOPICS!" So if an ETOY.share is not literally a share but can nonetheless be bought, acquired and exchanged, what is it? If etoy is not really a corporation but is nonetheless, at their own insistence, involved in effecting fluctuations in the market value of another company, their ‘rival brand’ so to speak, what is the art work’s relationship to its signified?

Surely what art risks when pastiche tips over into market manipulations and legal victories is the loss of the very thing that distinguishes it from its satirical victim: its own autonomy. Perhaps this sounds like an apology for a discredited ideal of disinterested art or ineffectual art, but it’s hard not to feel that etoy’s albeit ludic and PC deployment of markets isn’t achieving a too perfect symmetry with its dark other.

Josephine Berry <josieATmetamute.com>

Everything Must Go

If the CRASH! Corporatism & Complicity exhibition at the ICA didn’t live up to its Situationist swagger, was it more than just an exercise in recycling avant-garde strategies? Benedict Seymour asks what modes of resistance are left to artists in an era of ‘creative capitalism’, ‘Prada Meinhof’ and art for business’ sake.

"Ironic mimesis is not critique, it is the mentality of a slave!" It may be hard to fit on a badge, but this was one of the more resonant slogans plastered across the walls of London’s ICA in the dying months of the 20th century. Amid the slew of agit prop stickers and corporate Newspeak that formed the CRASH! show’s background hum of unrest, this testy aphorism hung in the air, needling at you and its surroundings. The phrase seemed to refer outwards to the banal self-reflexivity of the media, cultural recycling, the ‘anarchic’ mummery of licensed fools like Chris Evans or Jim Carey of which the show’s curators have written so harshly. But it also turned back on its immediate environment, drawing attention to the artists’ own varied but almost universal reliance on modes of subversive appropriation.

The ICA obviously didn’t feel as absolute about the psychic servitude involved in this strategy, declaring in the pre-show blurb: "The artists in CRASH! mimic a range of activities and services, from trading, marketing, spin doctoring, genetic engineering, and advertising to spying and hairdressing." Is there a margin for critical reflection in such techniques or do the institutions and discourses imitated overwhelm the art? What modes should an effective critical art deploy? And is ‘critique’ a proper vocation for art anyway? These were questions raised (but not necessarily resolved) by the show — and this precisely because of the curators’ unusually vocal commitment to a kind of engaged, socially conscious art not much witnessed in the ‘Cool Britannia’ ’90s.

Matt Worley and Scott King, already known for their self-published magazine, billboard subversions and style mag rants, co-ordinated this art gallery extension of their dissident media project in collaboration with the ICA’s Emma Dexter and Vivian Gaskin. Having made clear their impatience with the false liberations of postindustrial capitalism — from ‘flexible’ working to corporatised leisure — they now had a proper gallery with a selection of artists, activists and theorists of their choosing with whom to explore the themes of ‘Corporatism & Complicity’ referenced in the exhibition’s subtitle. Proclaiming that CRASH! would be "both a reflection and a condemnation" of contemporary life, this was an unusually ambitious, confrontational approach which would take some living up to.

The curators stressed their intention to break with the self-indulgence and harebrained trivia of recent British art, and emphasised a commitment to ideas, politics, and a less fetishistic conception of the artwork. Instead of decorative self-absorption and an obsession with ‘identity’, this would be non-commodified, performative and even artless art with a design upon its viewers’ minds as much as their senses / wallets. The artists were looking at some subjects already familiar from the work of their populist yBA forbears, "real and even banal everyday concerns" being a hot ticket in the arte povera 90s, but their ambitions were larger, encompassing the topics of work and money, consumerism and dissent, globalisation and investment, democracy and the market and the interpenetration of all of these.

In the Corporatism-and-complicity equation the latter could have been a reference to the general state of culture vis-a-vis the market, or specifically that of art, but for sure it was also a self-dramatising acknowledgement of the show’s own conditions of possibility. Colliding the neutral space of the office (Rachel Baker installed a temp agency for artists complete with desk and waiting room, Szuper Gallery engaged in online day trading near the entrance to the show) with the makeshift architecture of contemporary protest (Inventory erected a wigwam full of polemic and information — a centre of operations, not a piece of art ), the show as a whole was more ambivalent than the CRASH! boys’ rhetoric let on. If it lacked the wild energy of their punk rock heroes, preferring constructive dialogue and dissident focus grouping to riotous assembly (Kate Glazer hosted an ongoing discussion forum in the gallery and online called ‘Thinktank/ Mindpool’), the show did share punk’s proto-Thatcherite brazeness about feeding from the hand it was biting. It seemed both unnerving and appropriate that sponsorship should come from the 90s masters of ‘ironic’ retro advertising, Diesel.

Of course, corporate patronage is not exactly unusual, but Matt Worley’s noisy dissatisfaction with the ‘Prada Meinhof’ and the choice of this particular sponsor seemed to point up the ironies of art’s compromised position. Who better, cynics might ask, to fund a simulacral recycling of 70s political and conceptualist gestures than the arch recyclers of 70s kitsch? The CRASH! catalogue is punctuated with updated Situationist squibs and, sometimes, clumsy soixante-huiticisms ("Never work, Never Sleep", "Burn It Down", "London’s Burning With Boredom Now"), just as Diesel clothing’s influential ad campaigns deployed what you might call an ‘ironic mimesis’ of the mendacious high consumerist rhetoric the Situationists more maliciously détourned ("Diesel: for Successful Living"). Diesel were surely aware of the kind of non-conformism they were trying to align themselves with, since their pitch relies on their target group’s self perception as ‘different’, sophisticated and un-duped. As Worley himself has written, vampiric capitalism recently moved on from recycled kitsch to the exhumation and (unselfconsciously) ironic mimesis of the signs of its erstwhile antithesis: from Che Guevara bars and terrorism on t-shirts, to the e-commerce ‘revolution’ and the rehabilitation of Marx — the sign of capitalism’s material triumph is also the index of its symbolic feebleness. The superficial or not-so-superficial similarity of sponsors, curators and artists in relying on modes of pastiche and varieties of subversion just emphasised how ambiguous the return to a critical art might be in the current climate, whatever the convictions of those involved.

Could CRASH! escape from the potential neutralisations and make a show that was more than a blank parody of political dissent? Perhaps, despite the curators commitments, the artists weren’t too worried. All shared a suspicion of art’s once vaunted claim to autonomy, and their often textual or performative ‘pieces’ tended to emphasise that art, business and other kinds of work exist in a continuum: Janice Kerbel gave us meticulously detailed plans for a bank job, as if taking the old conceptualist ideal of art as an (uncommodified) blueprint for a work to be executed by others to its logical, materialist conclusion; Matthieu Laurette’s ‘art’ was the ongoing project of his subsistence, living, since 1996, on money-back products — an example of scrimping rebelliousness whose margin of aesthetic ‘freedom’ must become as routine and time-consuming as any other job.

On the other hand, beyond the preliminary assumption of art’s implication in everything else, there seemed to be important differences in orientation. The forms of simulation deployed by the artists, ranging from a direct (re)enactment of corporate work-leisure in the temple of art (Szuper Gallery’s day trading activities, Rachel Baker’s temp agency putting artists in touch with potential employers) through John Beagles and Graham Ramsay’s didactic appropriation of the schoolroom wallchart to present viewers with a neglected history of metropolitan protest (Wat Tyler Wot Happened?), to Heath Bunting’s (spoof ?) DIY kit for producing GM resistant weeds (Natural Reality Superweed Kit 1.0), were as diverse in content and agenda as they were unified in strategy. Perhaps it was this dependence on second order mimesis — whether imitating corporate discourse or directly intervening in its processes — that heightened the show’s homogeneity. Even when the general tone of the artists was polemical and combative, as with the Inventory group, the politicised discourse was freighted with self-consciousness. Their list of demands, scribbled across the slats of a Venetian blind that hung in the centre of the tent, was sincerely belligerent but ruefully and comically self-cancelling: "We Demand that Sweden be flatpacked and shipped to Kosovo! / We demand that artists… oh, forget it." Acknowledging the incongruity of the gallery situation and the intransigence of their audience, even enemies of ironic mimesis could not sustain a rabble rousing discourse without, well, irony. As Novalis wrote, despair is the most terribly witty state of all.

Where Szuper Gallery seemed to indulge a fascination with the abstraction of high finance out of a desire to probe the latter for possible points of weakness, Carey Young’s video Everything You’ve Heard Is Wrong got even closer to its imitated object. The video showed a corporate-suited Young presenting an immaculate rendition of a business communication skills presentation at Speaker’s Corner. As the straggle of passers by and oration-lovers gathered and dispersed in the foreground, a fervent Moslem demagogue could be made out at the edge of the frame, creating an odd collision of sacred and secular modes in this anachronistic relic of the old public sphere. The passion and depth of the one would contrast wryly with the neutrality and selfreflexivity of the other. And yet, despite their ostensible disparity, in form and content, both perhaps aspired to a perfected communion, and neither mode could have been foreseen by the Victorian burghers who inaugurated this space. A presentation on public speaking at Speakers Corner? The world had swung from Chartism to flowcharts. The circularity of the performance made one think of the cancerously proliferating business book business, and the post-literacy of their authors. The recursive loop of addressing an audience with a lecture about how to hold an audience’s attention, and the lecture’s title, which xeroxed corporate language but also turned it against itself, gave off a cool absurdism.

It might be tempting to read the performance as a parodic reflection on the frictionless corporate ideal of ‘communication’, the reification of the richness of language by a base functionalism. Yet the deadpan mode, which was funny but not that funny, distinguished her schtick from straight satire. In addition, Young’s own reported enthusiasm for developing the synergies between creative businesses and the business-like creatives who work for them mitigates against such an interpretation. Perhaps this was the ‘ironic mimesis’ condemned in the slogan, a habit (or ‘slave mentality’) of empty mockery adopted in order to sustain the banalisation of everyday life? (This is surely the logic of the ‘subversive’ current affairs comedy show, not so much an assault on the status quo as a device for coping with, and hence reproducing, it.) But, on the other hand, who said art had to issue in ‘critique’? The ambiguity and complexity of connotation here seems to me more interested in a Keatsian ‘being in uncertainty’ than a rush to either polemic or comic relief. If some of the CRASH! artists had already identified the enemy and the field of combat in advance, Young’s approach retained a ludic openness that should not be summarily written off as co-opted. Young’s practice, reformist rather than revolutionary in tendency, may accept the parameters of the brave new corporate world but in its sensitivity to the implosion of previously distinct categories could be more useful than reheating old battle cries for gallery consumption. As Young has suggested, creativity and imagination, the intellectual and conceptual dexterity traditionally the preserve of the artist, have become fetishised values in the postindustrial workplace. Where the CRASH! curators recoil in horror from this reification of human potential, Young seems to play with the possibilities of ‘personal development’. Taking the logic of the yBAs’ entrepreneurialism a step further, on closer inspection the CRASH! show could have been heralding the next stage in arts subsumption under capitalism as much as calling for its revenge.

The ambiguities of Young’s work contrast usefully with those of another video-documented performance: We The People by Beagles and Ramsey. At first sight similar to Young’s work in its incongruous intervention in the public sphere, the video shows the artists attempting to make contact with secret service agents and presenting a provocatively vacuous petition to 10 Downing Street (It read simply "We The People", as if commencing a list of demands then immediately giving up). Apart from the deliberate futility of these activities, the fact that the actors/ artists had assumed the iconic appearance of Taxi Driver’s postmodern antihero, Travis Bickle, from the proto-punk mohican and manic De Niro grin down to the army boots, upped the ludicrousness quotient. Again, the performance’s futile non sequiturs seemed calculated to expose the hollowness of an institution, the alienation implicit in democratic representation, within a comic mode now hyper-familiar from postmodern British TV comedy (think of Adam & Joe, or the routinised assimilation of Chris Morris’s innovations in the 11 o’Clock Show). But the identification with the psychotic, vengeful figure of Bickle — the isolated, skewed crusader of a corrupt post-Vietnam polis — cut both ways, suggesting more meanings than the piece could organise. Lost in the labyrinth of implications, the sense of disenfranchisement and atomisation evoked by the original film returned as bathos. Here the work didn’t get beyond its mimesis of an already over-familiar if ambivalent signifier, leaving the world as dizzyingly cluttered with references and depleted signs of representation as it found it.

One could summarise the difference between the CRASH! show’s artists less on the level of technique or address (since imitation was common to almost all) than in whether or not they hoped to wring a final refusal of the global situation out of the deadlock their work evoked; in the case of Beagles and Ramsay, Heath Bunting or the Inventory group, pushing towards a more radical gesture to which their art and theorising was a partial contribution, or on the other hand, with Young, accepting the indeterminacy of the postmodern condition, the apparent absence of alternatives, and turning one’s attention to improving conditions within these limits as a kind of expanded, executive aestheticism. But did any of the work on show give a taste of these potentials, a breath of the new, improved life latent in ‘the banality of everyday life’? Between the latterday Situationists — who consider art already superseded by activism and regard such gallery interventions as merely one weapon in the cultural terrorist’s arsenal — and the business artists — following Warhol’s trajectory out of the autonomous sphere of art and into the office — there seemed little to choose. Neither offered a compelling aesthetic jolt of alterity or opened up a sense of escape. Ultimately the show’s very dependence on the genres of corporatised and commodified culture made the latter’s presence suffocating — the artists almost seemed to be hiding in the cloak of the adversary, afraid to strike out into anything so arrogantly deluded as a self-sufficient work.

Except for Mark Leckey, that is. The only piece in the show that was willing to sell out to the sensuous, whilst confidently registering seismic cultural shifts, was his video (not a document of an intervention this time but a deconstructed montage of documentary footage), Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore. Shut away behind black rubber curtains in a club-like darkness and projected across the length and depth of the room, it was a disorienting and heady shot of image after the dry texts that preceded it. Like guilty voyeurs, viewers could finally indulge their sick taste for sensory stimulation and narrative pleasure in this history of popular dance culture from northern soul to acid house. Faced with the conceptualist mirror of late capitalism who could blame you for taking the traditional route and getting out of it by getting out of your head?

This was not in fact an ‘escapist’ film, however. The form was chronological but discontinuous, the significance of the changes in gesture, dress, and musical style registered in the diverse source materials not explicated for the viewer but offered up for analysis. But it did feel like a release after the preceding dialectic of indifference. Perhaps art, which admittedly has been fetishised as a site of play, ambivalence and otherness, is nevertheless suffering not from too much luxuriant, escapist incertitude, but too little. There is a danger that, following the lead of a newly humble and self-flagellant capitalism (which, after all, has borrowed its new clothes from earlier artistic and political ‘creatives’), artists will feel obliged to downplay art’s residual freedoms, hairshirting themselves into the same reflex of repentance that gives us reality TV ("we don’t want to make the viewer’s feel they are less interesting or important than the stars — plus we’re strapped for cash"). Meanwhile, beyond the confines of the gallery, the artists and activists had been upstaged by events in Seattle, an eruption of organised political opposition to corporate domination which made it all look suddenly rather academic. Ironic or what?

Benedict Seymour <ben AT bseymour.freeserve.co.uk>

Branded to the Bone

Chris Wilcha’s lo-budget documentary The Target Shoots First follows a post-punk rock-loving twenty-two year-old into the murky world of a large record company. Chris Darke compares his findings to those of Naomi Klein, author of No Logo, and to the criticism of the new American cultural order collected in the anthology Commodify Your Dissent. The question all three of these beg is: how far can one resist assimilation?

“The bourgeois scheme is that they wish to be disturbed from time to time, they like that, but then they envelop you, and that little bit is over, and they are ready for the next.” Claes Oldenburg, 1961

“It shouldn’t have been a shock, but it was.” Chris Wilcha, 1999

March to the Royal Festival Hall to hear a recital by the tabla virtuoso Zakir Husain. Projected above the stage was the logo of that evening’s sponsor, the financial services corporation HSBC. Nothing unusual about that; corporate sponsorship is so much a feature of high profile cultural events that the HSBC logo appeared as much in keeping with the evening as the musician’s arrangement of performance rug and flowers. But as an envoy from the Indian Embassy took the stage, name-checked the musicians, then introduced a representative of HSBC, a murmur ran through the audience which soon strengthened into a hiss of disapproval that hung over the auditorium. When Mr. HSBC began the customary spiel in which arts sponsorship is gently massaged away from being mistaken for a lucrative exercise in tax-loss philanthropy, the hissing became a sotto voce groan. By the time we were told about HSBC’s long relationship with the Indian subcontinent and about how many corporations have come to recognise that they have duties “beyond making a profit”, a slow handclap had started up, as if to express a collective sentiment of ‘Yeah, right’. Mr. HSBC then revealed he had a cheque to award to a worthy cause, which he proceeded to present to a representative of Unilever. A storm of hilarious derision broke over the unfortunate CEO, who retired from the podium having barely started his acceptance speech.

There was enough sheer ire in the air that night to suggest that, post-Seattle, even anti-corporate souls over here had tasted blood. In setting the stage for a performance of Indian devotional music with a soft-focus appeal to its colonial legacy, HSBC didn’t simply generate an unexpected PR-breakdown. Rather, it was a case of the public having a short fuse and little tolerance towards such juxtapositions. The audience at the Festival Hall expressed its hostility as outsiders given the uncommon privilege of shouting-down a mode of speech that has become a dominant form of public discourse. PR-spin is a language in which everything is addressed as product and everyone appealed to as a consumer and hostile rejection is a direct response to the saturation of the culture by this corporate vernacular. The vehemence with which this response was expressed requires that, in order to blunt it, the sharp men and women of corporate PR will have to wage a new, more concerted form of spin-warfare.

But what if an insider within the belly of promotional culture were to sustainedly train a camera on it, probe its etiquettes, crack open its contradictions and, with an almost naïve insistence, ask “What the hell am I doing here?” In May 1993, Christopher Wilcha, a 22 year-old philosophy graduate, went to work for Columbia House, the mail-order wing of Columbia Records, and took a Hi8 camera with him. Over the next two years, Wilcha gathered footage for a 70 minute tape, The Target Shoots First. Part video-diary, part counter-motivational training film, Target is that rare document – a sustained essay in corporate anthropology and a young Gen-Xer’s search for clarity in contradiction. It’s a work of well-balanced details, of analytical commentary elucidating anecdotal video-verité. Wilcha has a journalist’s sense of the facts that matter, so we learn early on that Columbia House is (was – there’s since been a merger) owned by Sony/Time Warner, that their combined revenue was $70 billion and that, as an employee, he’ll “have access to Sony and Time Warner’s cafeterias”. He also has the film-maker’s eye for the resonance in simple visual details: over shots of the empty and anonymous corporate corridors of his 19th floor eyrie his commentary remarks on “the weird institutional deja vu – the corporate workplace reminds me of high school.”

But fundamentally, Target is an essay in the processes of assimilation – of the kid by the corporation, of the kid’s music by the record company machine. “How naïve is that?” could be the po-mo(ronic) response to this precis of Target’s themes. But the film-maker’s no ingenue; he’s more interested in discovering whether it’s still possible even to be quizzical about the condition that Naomi Klein describes in her book No Logo as being “branded to the bone”. If the anti-WTO demonstrations proved anything it’s that it’s no longer enough just to raise an eyebrow and come over all resignedly mandarin about what the American journal of political satire The Baffler calls “the business of culture in the new Gilded Age”. To engage with it requires that one engage with the culture of business.

Wilcha’s time as Assistant Product Manager of Music Marketing at Columbia House coincided with two major developments in the music industry. First, there was the advent of ‘grunge’ with the major cross-over success of Nirvana’s Nevermind. Second, there was the change from vinyl to CD. “The ‘90s way of buying was to replace a vinyl collection completely,” Wilcha narrates. “Record clubs were one of the ways to do this.” Columbia House was reaching a market of 8 million subscribers a month but, as Wilcha discovered, was also ripping off its artists while reaping the dividends of sales and direct marketing. Artists would be paid reduced royalties and publishing rates on the sales of club CDs. These general infrastructural facts of music marketing are bought into focus by Wilcha’s own sense of cultural alignment with the alternative rock scene. With the release of Nirvana’s In Utero album, he’s put in charge of producing the magazine for Columbia House subscribers – the senior writer having resigned (the film’s good on the power-divisions between marketing types and ‘creatives’, the former working on the 19th floor, the latter subordinate on the 17th). Wilcha’s boss tells him: “This is a Gen X band. You can speak for them.” He duly writes the feature and finds himself “confronted by the fact that my identity as a punk rock fan and my job as a Columbia House employee have finally collided.” In gathering material for the film, Wilcha explores this dialectic while trying to demarcate some independent space: “For the past six months, taping has been a way of convincing myself that where I work isn’t who I am.” But it’s also a way of, if not reconciling the contradictions of his new-found corporate identity with his individual cultural identity, then bringing those contradictions into the open and of expressing a by no means fashionable uneasiness with the processes of appropriation and assimilation at play.

Yet Target is itself a document not so much compromised as complicated by its very access to internal corporate processes. I asked Wilcha if he was at all concerned that, in showing the film to management, he might realise that it could be the model of a new genre of media-savvy corporate training video? “The first screening (in 1999) coincided with a corporate merger,” he told me. “They [Columbia House] merged with CD Now, the giant online retailer, and the week of my New York screening was the week they were announcing the merger, so the screening was completely off the radar. Finally, in the weeks that followed, a bunch of upper management people, including the President, watched it. Some people disagreed with what I had to say. Others in management, comically enough, saw it as some kind of sociological study of a failed business experiment. They wanted to know how we could replicate that kind of consumer reaction on the web, instead of seeing it as an expression of how people felt about their jobs.”

As an ‘essay film’ – a hybrid genre of documentary observation and first-person intervention whose time has surely come round again – the strength of Target lies in the way it develops and explores its key theme of assimilation. Wilcha’s team produced a pilot version of the club magazine, successfully delivering a model for niche-marketing ‘alt.rock’ as well as ‘divulging club sales tactics, innovating the selection, sneaking in criticism – we put anything into the magazine we like.’ At which point, corporate assimilation takes yet another turn. “Management brings in an advertising agency who, for a fee, sell our idea back to the company. It shouldn’t have been a shock, but it was,” Wilcha relates.

The Target Shoots First can be seen as taking its place alongside the interventions and critiques of writers such as Klein and journals like The Baffler. It’s also of a part with, but at one remove from, the neo-Situationist, perceptual pranksterism of ‘culture jamming’. As a form of semiotic subversion, ‘culture jamming’ covers a range of art-based activism. From Adbusters’ satires on the values and techniques of advertising, through etoy’s interventions into the stock market exploring the porous boundaries between the business of art and the ‘art’ of business (see Mute 16), to rtMark’s overtly risky brand-sabotage activities, ‘culture jamming’ wagers – and in some senses seeks to redefine – avant-garde art strategies against the speed with which such strategies may be assimilated by their very corporate targets.

Wilcha, Klein and The Baffler represent a tendency that’s slightly different from this pranksterism – one that’s based on a necessary defensiveness in the face of the market without limits of reach and responsibility. The symptom of such defensiveness is to wrest back certain journalistic precepts – of investigation and independent critique – that should, by nature, be resistant to the glossy cant of marketing. Should be – but haven’t proved to be so. As media convergence has demonstrated, editorial values can quickly become hostages to advertising fortunes.

The value of the insights that Wilcha brings to bear on the coopting of ‘alternative culture’ is what really aligns Target with the work by journalists such as Klein and The Baffler. Culture becomes the field in which capitalism stalks the ever-newer ‘new’ and The Baffler has made analysis of this phenomenon its forte, along with the detailed institutional analysis of American journalism and union activity. The collection of ‘salvos’ from The Baffler published in Commodify your Dissent date from around the mid-90s but remain relevant in their splendidly distempered take on corporate culture as it chases, in ever decreasing circles, after the spectacle of the counter-culture until, as predicted, pop eats itself. And business picks up the tab. In the tail-chasing flurry of hungry assimilation, culture became marketing and marketing culture. In his 1995 essay ‘Alternative to What?’, Thomas Frank, co-founder of The Baffler, writes: “There are few spectacles corporate America enjoys more than a good counterculture, complete with hairdos of defiance, dark complaints about the stifling ‘mainstream’, and expensive accessories of all kinds. So it was only a matter of months after the discovery of ‘Generation X’ that the culture industry sighted an all-new youth movement, whose new looks, new rock bands, and menacing new ‘tude quickly became commercial shorthand for the rebel excitement associated with everything from Gen X ads and TV shows to the information revolution.”

The fear that both Wilcha and Thomas Frank identify with is that all ‘deviant’ cultures are so rapidly assimilated, that it’s increasingly difficult to out-manoeuvre the mainstream and that corporate culture is frighteningly adept at absorbing its dissident voices. ”I think it’s often very hard for Americans themselves to see what’s going on,” admits Frank. “One of the comments we keep getting from our readers’ letters is that they didn’t think that criticism like this still went on. We hear that all the time. In the US, the labour movement has really fallen off the cultural map. Thirty years ago every newspaper in the country had a labour reporter. Now the only ones that do are The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and The Chicago Tribune. Organised labour has to be the wellspring of scepticism towards the corporate universe. When those people showed up in Seattle, and a lot of them were from unions, this astonished people, they thought unionism was over in America.”

There is, inevitably, a generational issue here, a question of a shared cultural and political memory that corporate culture does its best to undermine and erase. Hence the accuracy in critiques of cultural ‘dumbing down’, where infantilisation of the public incubates precisely the willed, induced amnesia that makes a good, loyal consumer out of a former citizen with a cultural life and political allegiances. In this respect, Wilcha is smart to compare his absorption into the corporate world of work with that of his father, and understands that his is one of the (last?) generations with a sense of self that could still be located outside of the mall. “What my father went to business school to study,” he narrates, “I trained for simply by being a committed consumer.” In conversation he told me: “I’m 28 years old now and for a lot of kids who are around 25 – they’re labelled Generation Y – these concerns are invisible to them. If you’re in a band now, it’s no longer a question of selling out as far as having your music in advertising is concerned, it’s part of the marketing plan! It’s a given. Literally it’s been in the space of a couple of years that there’s been a whole change in consciousness about the relationship between art and commerce, with culture being used to prop up and sell things.”

We’ve been here before. Maybe we’ve been nowhere else since the 1950s. The professional Jeremiahs of Wilcha’s father’s generations were Vance Packard, author of The Hidden Persuaders, and Consumer’s Rights supremo Ralph Nader. Perhaps between them, Wilcha, Frank, Klein and others of their growing number might restore and revitalise critique, satire and analysis to the vital work of cultural analysis that exists outside of academia’s self-absorption. One that understands that ‘culture’ means more than the miasma produced by the multinational entertainment oligopoly where, in Don DeLillo’s phrase, “nothing happens until it’s consumed.” Perhaps we’re in for a new generation of characters (after all, in Target, Chris Wilcha is ‘Son of Organisation Man’) who haunt the corridors of corporate culture with their hostility and confusion yet to be dulled and bought off. Or perhaps we’ll just wake up one day, niched to within an inch of our lives.

Chris Darke <chris AT metamute.com>

Culture Clubs

New Labour orthodoxy maintains, in line with its predecessor, that public private partnerships are the only way forward economically. Transport, health and education have been the most controversial new enterprise zones, but is the cultural sector's restructuring any less absolute? Anthony Davies and Simon Ford report

Where corporations once sponsored art and culture, they now ‘co-produce’ it. Where their structures used to be rigidly hierarchical, they are now flexible and networked. These shifts render unworkable all sorts of categories we used to employ when distinguishing between the public and private spheres. In an effort to identify the often elusive architecture — and architects — of the new cultural economy, Anthony Davies and Simon Ford report on a representative sample of Third Way alliances.

Today, a new variety of club is emerging: a type of club dedicated to the networking of culturepreneurs and the business community. Much of this activity has been in line with organisational and structural shifts occurring in the corporate sector — principally, the shift from centralised hierarchical structures to flat, networked forms of organisation. In this report we look at how these networks and ‘new’ economies are being formed, accessed and utilised, where they converge and where they disperse.

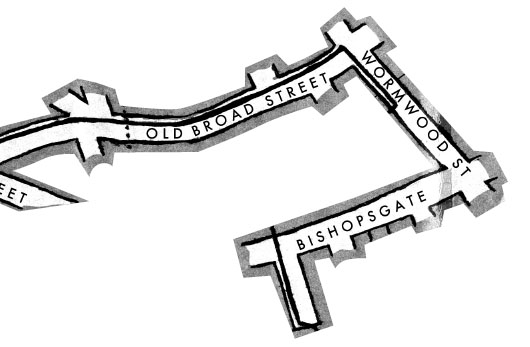

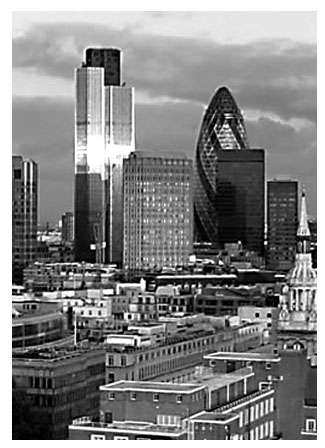

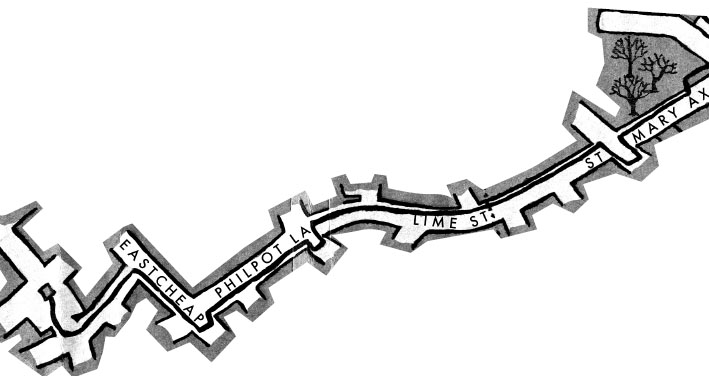

In the late 1990s the surge to merge culture with the economy was a key factor in London’s bid to consolidate its position as the European centre of the global financial services industry. Culture was part of the marketing mix that, within the context of the European Union (EU), kept London ahead of its competitors, particularly Frankfurt.<1> This can be traced back to the UK’s exit from the Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992 and a range of economic initiatives aimed at attracting inward investment, or Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). During this period the UK accounted for 40 per cent of Japanese, US and Asian investment in the EU. ‘Cool Britannia’ may have been a media spectacle, but it was the need to attract FDI, combined with the co-ordinates of a new service-based economy, that underpinned London’s spectacular emergence as the ‘coolest city on the planet’. (This state of affairs could be about to change with the proposed link-up between Frankfurt’s Deutsche Börse and the London Stock Exchange (i.e. the iX market) and the recent German tax reforms that will pave the way for a radical restructuring of its corporate landscape.<2> With higher international inward and portfolio investment and the combined iX market, Germany looks set to become the leading market destination for young companies, making Berlin’s pitch to become the new cultural ‘it location’ look increasingly viable.<3>)

In London it was the cultural requirements of the ‘new’ economy that resulted in the emergence of culture brokers — intermediaries who sold services and traded knowledge and culture to a variety of clients outside the gallery system, from advertising companies and property developers to restaurateurs and upmarket retail outlets. Job descriptions such as artist, curator, critic and gallerist no longer reflected the range of activities these individuals were engaged in. For culture-brokers art production was just one element that, along with the music, drug, fashion, design, club and political scenes, could be brought together, mediated and repackaged in a range of formats, from exhibitions and websites to corporate parties and instore merchandising.<4> At the same point many companies were beginning to move away from sponsorship towards an integrated partnership or alliance strategy. This marked a further shift from the ‘something for nothing’ arm’s-length philanthropic model to a ‘something for something’ contract in which marketing departments perceived cultural (and often environmental) programming as an integral part of ethical marketing strategies (the so-called Total Role in Society).<5>

Along with these new developments corporate strategists realised that, because of the emerging knowledge-based economy, a company or individual could be valued principally on ‘intangible assets’ (e.g. intellectual capital and access to networks). This brought about a revolution in the corporate sector.<6> The underlying trend has been to develop flatter, more flexible and intelligent forms of organisation. This, in turn, has put pressure on companies to form alliances and break down inflexible departmental structures and initiate cross-departmental project teams (increasingly staffed by short-term or outsourced contract workers). Indeed, we have recently witnessed the birth of an alliance culture that collapses the distinctions (or boundaries) between companies, nation states, governments, private individuals and even the protest movement, as we shall demonstrate later. This trend towards alliances and partnerships has resulted in what have been variously described as ‘virtual’ or ‘boundary-less’ organisations. It has also made it increasingly difficult to identify ‘cores’: as companies loosen their physical structures through outsourcing, concerns have also been raised about the danger that core activities are disappearing, leaving fragile shells or ‘hollow’ organisations.<7>

A number of corporate organisations are currently gauging the potential of extending their networks into strategic alliances with other sectors, particularly the public sector.<8> This new alliance culture between the public and private sectors can be seen within the context of the UK government’s drive to establish a Third Way in which ‘public’ is no longer equated solely with ‘the state’, but with a combination of public/private agencies. With the private sector leading the way, public institutions are undergoing an ideological and structural transformation to make themselves more compatible with corporate alliance programmes. Like their corporate partners, many cultural institutions now perceive their role as ‘hanging out with culture’, interacting with and being part of it. In their drive to formalise informality, they provide what are essentially convergence zones for corporate and creative networks to interact, overlap with one another and form ‘weak’ ties. The prominence that events such as charity auctions, exhibition openings, talk programmes and award dinners have attained demonstrates how central face-to-face social interaction is to the functional capacity of these new alliances.

Some institutions go further. At London’s Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), for example, a networking club for cultural entrepreneurs and, initially at least, educationalists, arts administrators, television executives and business consultants has been set up in conjunction with Goldsmiths College, the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (NESTA), Channel 4, the Arts Council and Cap Gemini.<9> The Club is coordinated by Andrew Chetty and Sarah Duke at the ICA, Andrew Warren at Cap Gemini and Alan Phillogene at the Centre for Cultural Studies at Goldsmiths College. It is an invite-only monthly event that provides "a networking base for its members" and promises to introduce them to agencies from television companies to venture capitalists and private organisations who "may wish to support and commission them".

Through initiatives like The Club the ICA aims to become the leading institutional home for cultural entrepreneurs and perceives its role as a facilitator and "ideal forum for the cross fertilisation of ideas, and support base for these enterprises".<10> After the success of the first two meetings at the ICA, the third will reputedly take place at Channel Four in September. Such nomadism indicates that The Club itself has no fixed base or home and can move to any location within the network. This makes identifying the core organisation difficult and, in line with the complex and often hidden alliances that characterise the new corporate landscape, it raises serious questions of transparency, representation and accountability.

Given their foregrounding of The Club’s ‘development and growth’ potential, its coordinators must be aware of the current sale talks surrounding First Tuesday, the market leader of match-making clubs for internet entrepreneurs and venture capitalists. With 100,000 members on its database and the claim to have raised $150m in seed capital from its networking events, it is no surprise that its valuation of £33.5m was based principally on access to its "extensive database of the digital elite".<11>

A variety of means exist to finance these clubs. First Tuesday take a two per cent commission on deals, while other culture clubs generate capital through membership (The Fourth Room) or building the most "influential list of contacts in the world" (Free Thinking). With the creative industries generating £60bn a year (seven per cent of national gross domestic product) and estimated to increase at a rate of 5% per year, it is no surprise that The Club is endorsed by both government agencies (NESTA) and private companies.

At this stage it is difficult to locate the mutual bonds and orientation of The Club, but it is a good example of the emerging inter-organisational relationships that characterise the ‘new’ economy. With representatives from the corporate, state, media, educational and cultural sectors, it may also represent the initial stages of a corporatised future for UK cultural and educational institutions. This falls in line with the forthcoming DTI spending review, which aims to refocus its funds into promoting enterprise, small business and ‘knowledge transfer’ and to "concentrate on managing change rather than attempting to direct companies’ activities."<12>

In the education sector ‘knowledge transfer’ translates into an £80m fund (the University Innovation Fund) to establish consultancies that will mediate between universities and businesses. With the ICA and Goldsmiths College stepping up contact with Cap Gemini and providing a "support base (and provider) for enterprise", the so-called revolutionary venture capital models proposed by companies like The Fourth Room come into the equation.

The Fourth Room was set up by former Chairman of The Research Business Wendy Gordon, founder of brand consultancy Wolff Olins Michael Wolff and former head of strategy at Interbrand Newell and Sorrell Piers Schmidt in 1998 as a hangout zone and creative bolt-hole for corporate executives and other ‘leading individuals’. It has been variously described as a business development club, a networking club and a strategic marketing consultancy which aims to take the strain out of networking and "put together venture ideas and management teams and take them from the moment of thinking through to the patent or crystallised idea".<13>

The £10,000 per annum membership fee includes use of the clubhouse in central London and access to "focus groups comprising of [sic] ‘ordinary’ people and teenagers who will act as sounding boards for new ideas".<14> In addition to the clubhouse, members receive a weekly in-house publication and an opportunity to eavesdrop on "emerging cultural trends and monitor changing patterns and beliefs".<15> This is described by the company as a corporate early warning system. As with The Club at the ICA, very little information is publicly available, but we know that The Fourth Room is "dazzlingly white, with high ceilings, long windows and white painted floorboards" and that members are encouraged to draw on the walls with coloured crayons to release their creativity.<16> As Piers Schmidt claims, "it’s all about collaboration", and to this end the aim is to get CEOs mixing with eco-activists like Swampy to discuss environmental issues over breakfast.

The relationship between Cap Gemini and the ICA and Swampy’s proposed breakfast with CEOs at the Fourth Room indicates that terms such as ‘collaboration’ can be utilised to mask a variety of vested interests. The recent shift in terminology regarding arts funding (i.e. away from ‘sponsored by’ towards ‘co-production’, ‘in partnership with’, ‘in association with’ and ‘co-produced by’) is also indicative of a new agenda based on alliances and an increased corporate decision-making role in cultural programming. A signal event in this diversification was the UK-based Association of Business Sponsorship of the Arts (ABSA) rebranding itself as Arts & Business (A&B), in the conviction that "the arts are the new secret weapon of business success". As a government funded organisation A&B have taken collaboration and alliances a step further through the Professional Development Programme and the NatWest Board Bank, which has placed 1500 young executives on the boards of arts companies.<17>

The Creative Forum members at A&B, who include American Express Europe, Arthur Andersen and Interbrand Newell and Sorrell, are seen as the ‘shock troops’ in the involvement of arts in companies and as a result A&B receive £5.05m a year from the government to run the Pairing Scheme. The arts organisations, it is claimed, gain from the decision making and entrepreneurial skills of the executives, while the executives gain valuable experience in creative processes through working with artists.

Other examples of recent collaborations follow an informal, networked and often hidden alliance-type arrangement between galleries, public institutions and corporations. An alliance-type project covered by this new lexicon is the Fig-1 website, project space and club founded by curator Mark Francis and gallerist Jay Jopling and financed by Bloomberg, the financial information company. Fig-1 aims to present 50 projects in 50 weeks; given such a collaboration, the claim to be simultaneously "in association with" Bloomberg and "independent, non-profit [and] free from institutional and commercial obligations" seems curiously paradoxical.<18> Rather, it appears that Fig-1 operates as a (principally new media) satellite organisation for White Cube and a cultural scratch-and-sniff site for Bloomberg.

We turn finally to a consideration of what might be termed ‘political engagement’. In order to meet the challenge posed by these new alliances and networked global businesses, new forms of flexible and subversive organisation have emerged that can disperse and re-form anywhere, at any time.<19> These strategic movements also take into account the fact that company networks and hollow organisations actively solicit and harness counter discourses to service the illusion of dissent and dialogue.<20> In a networked culture, the topographical metaphor of ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ has become increasingly untenable. As all sectors loosen their physical structures, flatten out, form alliances and dispense with tangible centres, the oppositionality that has characterised previous forms of protest and resistance is finished as a useful model.

In the cultural sector (particularly the ‘cutting edge’ art world), with so many brokers acting as corporate-friendly conduits to an artificially constructed ‘outside’, ‘marginal’ and ‘socially engaged’ culture, it should come as no surprise that these oppositional metaphors, for some, are difficult to dispense with.<21> Yet in contrast to such attitudes, more astute activists and agitators who once spoke of critical distance now recognise that their challenge lies in the forms and quality of access and connection. Fittingly, a useful new metaphor for this challenge comes from the world of digital systems. In a networked society individuals and groups are constantly alternating between ‘on’ and ‘off’. As a result we can expect to see emerging new forms of ‘engagement’ which exercise border controls on networks, withhold, filter and restrict access to information and disable ‘eavesdropping’ strategies and ‘early warning systems’ employed by business consultancies, corporations and public institutions.<22> The extent and nature of these forms is still to be determined and will be examined more closely at a later date. But it can already be asserted that informal networks have become extremely effective forms of counter organisation in the sense that — just as with corporate alliances — it is extremely difficult to define their boundaries and identify who belongs to them. Informal networks are also replacing older political groups based on formal rules and fixed organisational structures and chains of command. The emergence of a decentralised transnational network-based protest movement represents a significant threat to those sectors that are slow in transforming themselves from local and centralised hierarchical bureaucracies into flat, networked organisations.

These developments are taking place against a backdrop of waning confidence and belief in the ability of governments to regulate the growing power of global corporations and their networks of influence. But thanks to corporate restructuring and the access it provides to global networks, new forms of knowledge-based political engagement promise possibilities and scales of effect previously unimaginable.

Anthony Davies and Simon Ford <sford AT metamute.com>

FOOTNOTES:<1> Graham, George, ‘Overseas banks warned on London’ and Graham, George and Timewell, Stephen, ‘City confident of keeping status’, The Banker supplement, Financial Times, 27 November 1997.

<2> Grass, Doris and Boland, Vincent, ‘Deutsche Börse board split on link up with the LSE’, Financial Times, 13 July 2000; and Simonian, Haig, ‘German tax reforms set to aid investors’, Financial Times, 15 July 2000.

<3> Powell, Nicholas, ‘Avant-garde flock to Berlin’, Financial Times Weekend, 3/4 October 1998.

<4> For a fuller discussion of these developments see Ford, Simon and Davies, Anthony, ‘Art Futures’, Art Monthly, no. 223, February 1999.

<5> For a discussion of this concept see Law, Andy, Open Minds, London: Orion Business, 1999; and Alburty, Stephen, ‘The Ad Agency to End All Ad Agencies’, Fast Company, no. 6, December 1996.

<6> The INNFORM research programme found widespread initiatives in almost all new forms of corporate organisation in the period 1992-1996. See Whittington, Richard et al, ‘New notions of organisational fit’, Financial Times, 29 November 1999.

<7> Centre for Research in Strategic Purchasing and Supply (CRISPS). Returning to core or creating a hollow? Bath: Bath University, 1999.

<8> See Capital Strategies, the city corporate finance house, ‘Education News’ at [http://www.capitalstrategies.co.uk]

<9> Cap Gemini Ernst & Young is one of the world’s largest management consulting and computer services firms and has collaborated with the ICA on previous occasions, most notably Imaginaria ’99. The ICA’s definition of ‘cultural entrepreneur’ is derived from an earlier collaboration with Demos. See Leadbeater, Charles and Oakley, Kate, The Independents, Demos: London, November 1999.

<10> Duke, Sarah, The Club press release, 14 June 2000.

<11> Daniel, Caroline, ‘First Tuesday in sale talks’, Financial Times, 20 July 2000.

<12> Brown, Kevin, ‘DTI allocated funds to boost enterprise’, Financial Times, 17 July 2000.

<13> Schmidt, Piers, ‘Me and My Partner: Michael Wolff and Piers Schmidt’, The Independent, 7 April 1999.

<14> Jones, Helen, ‘Help is at hand to make the right contacts’, Financial Times, 12 February 1999.

<15> The Fourth Room, Invitation booklet, London: The Fourth Room, 2000.

<16> Deeble, Sandra, ‘Fourth Room opens the doors of perception’, Financial Times, 30 December 1999.

<17> See the Arts & Business website [http://www.absa.org.uk]; and Thorncroft, Antony, ‘From a cosy warm glow to hot support’, Financial Times, 6 September 1999.

<18> See its website [http://www.fig-1.com]

<19> See, for example, Vidal, John, ‘The World@War’, The Guardian, Society Section, 19 January 2000.

<20> See Knight, Philip ‘A forum for improving globalisation’, Financial Times, August 1 2000, and Tomkins, Richard, ‘Global chief thinks locally (Douglas Daft is persuading protestors to drink cans of Coke, not smash them)’, Financial Times, August 1 2000.

<21> See Art Monthly, Editorial, February 2000, No 233: "It is hard to resist the lure of direct action, particularly for those of us frustrated by the inexorable process of commodification of even the most critical art practices, and by the marginal position occupied by art in our society as a whole." And exhibitions: ‘Unconvention’, Centre for the Visual Arts in Cardiff, November 1999 - Jan 2000, and ‘Crash’, Institute of Contemporary Arts, November 1999.

<22> See Carpenter, Merlin and Davies, Anthony, ‘The protest had already impacted on London in the form of its absence’, from the catalogue As a painter I call myself the estate of, Secession, Vienna, 2000.

Learning the Right Lessons

Whatever happened to tactical media? David Garcia, one of the genre’s early formulators, takes C6’s recent publication DIY Survival as an opportunity to reflect on the general state of cultural politics after its net propelled reinvention in the `90s. Concerned with the commercial cannibalisation of tactical media, he identifies a need to connect its ‘hit and run’ ephemerality with more permanent structures of resistance

In 2005, the London based artist/activist outfit C6 published DIY Survival, a short book to coincide with their show, Sold Out. In the intro C6 declare their aim to ‘produce a guide of tactical means for collective art making’. The result is an amalgam of bits and pieces, ranging from the serious and helpful through to the self-mocking and frankly trite. This material has been helpfully divided into three sections: DIY Theory, DIY How To and finally DIY Case Studies. Part of the book’s patchiness might be the result of a decision to minimise editorial intervention. Whether there was any selection is not quite clear. The intro tells us that the contents are the result of an open call put out to a number of sympathetic internet mailing lists, but it is unclear whether there was any further editorial selection or intervention. We are simply told that they were ‘immersed in a flood of responses’ and ‘decided that their task was to let chance take over’.

It is clear from the outset that this book addresses the area of practice that, a decade ago, some of us dubbed ‘tactical media’ – although C6 wisely avoid a term that has already become quasi-institutionalised. Nevertheless most aspects of what could be described as tactical media are represented in this book.

The term was originally coined to identify and describe a movement which occupied a ‘no man’s land’ on the borders of experimental media art, journalism and political activism, a zone that was, in part, made possible by the mass availability of a powerful and flexible new generation of media tools. This constellation of tools and disciplines was also accompanied by a distinctive set of rejections: of the position of objectivity in journalism, of the discipline and instrumentalism of traditional political movements, and finally of the mythic baggage and atavistic personality cults of the art world. This organised ‘negativity’ together with a love of fast, ephemeral, improvised collaborations gave this culture its own distinctive spirit and style and helped to usher in new levels of unpredictability and volatility to both cultural politics and the wider media landscape. But this was long ago and the practices have long since become a familiar part of the media diet. So the question arises as to whether or not C6’s DIY Survival is taking us anywhere new. Whatever the answer, it should at least give us the opportunity to take stock, and ask whether any parts of this kind of practice retains value or credibility in a world it helped to change.

The cover of DIY Survival is sharp and funny and immediately raises expectations. It is a clever simulation of an ‘Airfix’ style model building kit, featuring one of those ubiquitous plastic frames to which the components of model Apache helicopters, Sherman tanks and so forth were attached. But in this version we find instead the miniature parts needed to construct today’s media ‘freedom fighter’: camcorder, lap-top, balaclava, graffiti spray can etc. Although the book’s cover can compete for attention with anything on the magazine rack, once inside we are transported back into a ghetto – the world of the 1970s fanzines. There is even an ironic (I hope) nod to the punk godfathers of DIY culture, with endless images of safety pins appearing to hold the disparate bits of content together. Of course it’s all very knowing, displaying a desire to recuperate the fast and furious punk ethos using 21st century Print On Demand technology. The trouble is C6’s DIY Survival suffers badly in comparison with the angry high-octane visual flare of punk. It is not that this uniquely English sense of failure, madness and defiant hedonism has disappeared, but you’d be better off looking for it on the NeasdenControlCenter website or watching an episode of Black Books or even listening to the Baby Shambles.

But if we are able to turn a blind eye (and it’s difficult) to the style problems, there is some useful and informative stuff to be found, particularly in the DIY How To section which includes the hacklab mini-manual for building Linux networks from cast off terminals and a piece with tips for creating a wireless node. But all too often the good stuff is undermined by cheesy, cop out, self-mockery such as the ‘How to be a Citizen Reporter’ photo-style guide or the risible cardboard cut out for ‘Robot Buddies’. The accumulated effect does little more than suggest an enclosed micro culture every bit as self-regarding as the white cube art it purports to undermine.

The Homeopathic Option

In the DIY Theory section there are some valuable moments, but it would have been so much more accessible (or just readable) with a more active editorial presence. For instance, it is great to have some of the distinctive rhetorical style of Brazilian ‘Midia Tactica’ in Hernani Dimantas’s piece ‘Linkania – The Hyperconnected Multitude’. But the text’s value is undermined by too many unexplained references, such as one to Globo – Brazil’s near monopolistic media giant. On the level of detail this is a trivial complaint, but more importantly without some clearer context we lose a sense of the uniquely Brazilian ‘cannibalistic’ interpretation of media tactics.

Wisely the book chooses to kick off with its most coherent and tightly argued essay, Marcus Verhagen’s 'Of Avant Gardes and Tail Ends'. This piece is worth closer examination not least because it could be assembled into if not exactly a DIY Survival manifesto then at least an articulation of its core belief in art’s sovereign role as subversive agent. For the most part the text is a brief history of the gradual erosion of the avant garde’s subversive bite. Verhagen makes useful but overly simplified distinctions, such as his opposition between the ‘critical’ and the ‘hermetic’ avant garde. One of his most telling points is to have identified the way in which art has relinquished any aspiration to depict utopias in anything but ironic form. ‘The utopian imagery’, he writes, ‘once conceived by Signac and Leger as force for social renewal, is now the preserve of Benetton and Disney. How often are utopian visions offered without irony in contemporary art?’

This is just one of the arguments Verhagen mobilises to insist that the critical art and media which orientate themselves to traditional fine art contexts are pointless since the real power now lies elsewhere. He describes the contemporary landscape thus, ‘Hollywood film, the magazine advertisement, or hit single: these constitute a more powerful force than the concert hall or the museum, they more faithfully represent the dominant values of the day and are better suited to co-opting avant-gardist work; after all commoditisation is more effective than canonisation’.

In the last few paragraphs of the essay, Verhagen advocates deploying Frederic Jameson’s ‘homeopathic strategies’ that seem to consist of a Foucault-like process of ‘unmasking’ power – a form of ideology critique carried out with images. It is hard to see how this differs from the approach which has become a familiar part of visual art’s currency since the first wave of critical post-modernism of the 1970s and 80s where mass cultural phenomena are examined and reproduced to ‘reveal their internal workings, their means and objectives.’

Verhagen goes on to claim that ‘homeopathic works are more difficult for the mainstream culture to appropriate because they are already in some sense part of it.’ This is all too true but, far from representing the ultimate in subversion, such an approach results in producing mere epiphenomena of communicative capitalism not only tolerated but consumed by it with relish. It is not that cultural or information politics are not important, it is just that outside of a broader context and strategy of meaningful confrontations they are simply not enough.

In his final clarion call Verhagen declares that ‘the grand subversions of the nineteenth century are coming to seem almost quaint, homeopathic tactics are surely more effective’. I would argue that the direct opposite is the case. It is only when the ideology critiques of image (or code) are deployed as part of a more general strategy of direct action that things start to move. The case of the AIDS activist campaigning group ACT UP’s use of visual tactics in the 1990’s are a classic demonstration of how cultural politics can have real power.

Telestreets’ Dilemma

The report on the Italian Telestreets movement by Slavina Feat (mysteriously placed in the DIY How To section) encapsulates the limitations of the book whilst at the same time pointing to an instructive example. The report is about the Italian micro TV movement Telestreets and a sister organisation New Global Vision, a collective of Italian hackers who have used BitTorrent to disseminate an archive of radical political video on the net whilst also helping Telestreets to distribute local content nationally.

Feat’s report is another of DIY Survival’s missed opportunities. It goes no further than re-cycling the familiar Telestreets hype that has been doing the rounds for a couple of years. It fails to raise the questions that we need to ask about this movement. To begin with what is the status of the network today? Is it growing or shrinking, or did it, (as I suspect, but do not know) reach its high watermark nearly two years ago? Is Telestreets now in decline, or worse, in the process of fragmenting under the weight of its own internal contradictions? Surely a book with a critical agenda must aspire to more than publicity puffs like this.

The Telestreets example is important because it embodies some of the starker choices for those involved in tactical media. These dilemmas were already visible in a Telestreets meeting, which took place in Senigallia in 2004. This meeting coincided with the moment that the infamous Gasparri law was being pushed through the Italian parliament. This law, named after the then minister of communication, allowed Berlusconi to consolidate his domination of the Italian mediascape.

Nothing defines the connection between media power and political power so well, because so crudely, as the Berlusconi phenomenon and the passing of this bill. So given the fact that this was a defining moment for Telestreets, the choice to hold the meeting in Senigallia, a small coastal resort was surprising. Although there were good reasons for this choice, Franco Berardi (Bifo) lead a number of dissenting voices in arguing that Telestreets had missed the boat and that they urgently needed to raise the stakes and focus their energies on mobilising resistance against the Berlusconi regime. By over emphasising expressive or artistic interventions and micro-media at the expense of direct confrontation, Telestreets was slipping into irrelevance. Bifo ended his ‘hair raising’ speech by declaring ‘the last thing we should be doing is embrace our miserable marginality’.

The Old Split

This Telestreets anecdote illuminates three interconnected tendencies that have emerged since the tactical media of the ‘90s. Firstly there is a widespread rejection of the homeopathic and the micro-political in favour of ambitions scaled up to global proportions coupled with a willingness to move beyond electronic and semiotic civil disobedience and to engage in direct action, to literally ‘re-claim the streets’. This is almost entirely as a result of the emergence of the powerful global anti-capitalist movement that (from its perspective) has transformed tactical media into the ‘Indy-media’ project. But there is also a third less visible and more troubling tendency, a tendency towards internal polarisation. This polarisation is based on a deep split which has opened up between many of the activists at the core of the new political movements and the artists or theorists who, whilst continuing to see themselves as radicals, retain a belief in the importance of cultural (and information) politics in any movement for social transformation. Although I have little more than personal experience and anecdotal evidence to go on, it seems to me, that there is a significant growth in suspicion and frequently outright hostility among activists over the presence of art and artists in ‘the movement’, particularly those whose work cannot be immediately instrumentalised by the new ‘soldiers of the left’.