Heavy Opera

John Jordan and James Marriott’s operatic audio tour set in London’s Square Mile is intended to awaken city workers to the impact of financial systems on climate change. But not only does And While London Burns misgauge how much the suits already know, its hysterical tone also harmonises too easily with the coming new eco-order

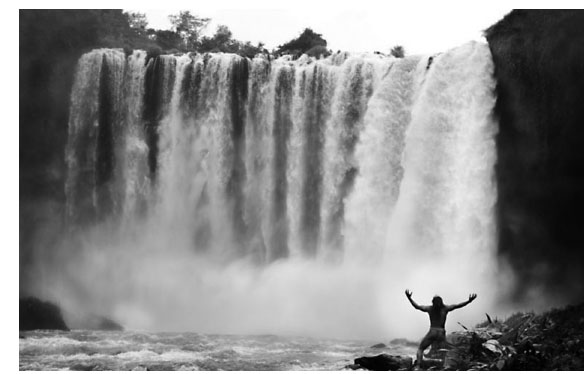

A fountain of water from the river Walbrook shoots up above my head, drums are pounding, a sound system’s bass rumbles. I hear cheers but I can also hear the clatter of police shields and batons around the corner. Seven years after London’s Carnival Against Capital, when protesters outside the LIFFE exchange broke a water mains sending a thirty-foot jet of water into the air, I am walking just a half a mile north of the same spot. Now I can hear the Thames rushing up the valley the Walbrook follows, bursting its banks, laying waste to the tall glass-fronted buildings as some of the most expensive real estate in London collapses around me. I’m swept up in a sonically induced fantasy driven by the tracks on my MP3player. I am taking part in And While London Burns, an operatic guided walk written by John Jordan and James Marriott, set to music by Isa Suarez and produced by the cross-disciplinary art and education group Platform.1

John Jordan has played a role in both these participatory dramas, firstly as a member of Reclaim the Streets – one of the anti-capitalist groups that coordinated the Carnival Against Capital in June 1999. This time around as an artist commissioned by Platform – an interdisciplinary arts, campaigning and research group committed to longer term, less partisan approaches to transforming the activities of the financial institutions and corporations with head offices in the Square Mile. The walk is an attempt to dramatise the research Platform has conducted into climate change. James Marriott, its co-founder, explains:

It's a way of dramatising and humanising these systems [the role of multinationals and financial systems in fuelling climate change]. It's over-dramatised like all opera, which is why we chose the medium.2

The walk begins at 1 Poultry. At a Starbucks opposite the ruins of the Roman Temple of Mithras our attention is drawn to the multinational’s logo with its allusions to paganism and older gods. The audio tour’s protagonist remembers that before Starbucks went global its logo (designed after a 15th century print by Seattle hippy entrepreneurs) bore nipples and ‘a pair of provocatively spread fishtails’. The mermaid allegorises both allegiance to, and fear of, the sea. She is exotic and, like the valuable cargoes on which the City’s wealth was originally founded, unattainable for those doing the shipping. The City is still resplendent with powerful iconography from the 18th and 19th centuries, pineapples and other exotic objects appear frequently as architectural ornaments advertising the City’s plunder. Today, retail spaces and spaceship architecture adorned with surveillance cameras predominate. At the Royal Exchange (now a luxury shopping mall) our protagonist remembers:

I used to work here in 1989, when it was the Futures Exchange ... the place was a permanent carnival, traders in bright coloured jackets shouting and gesturing to each other ... it couldn’t be more different now.

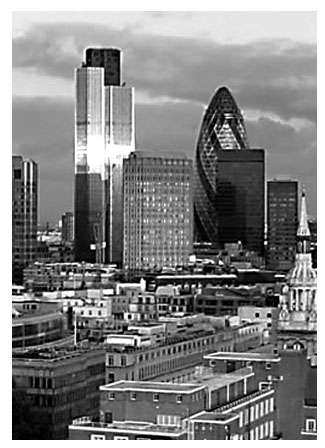

The new City outwardly tells little about where it draws value from and it is this occultation of money the walk confronts by whispering its secrets in your ear.

As its website explains:

For over 20 years, PLATFORM has been bringing together environmentalists, artists, human rights campaigners, educationalists and community activists to create innovative projects driven by the need for social and environmental justice.3

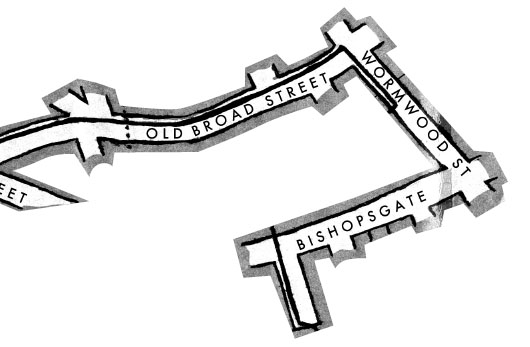

Platform has gone some way beyond the statements required to declare oneself a corporate entity in the art world. Operating more like an NGO, Platform sought autonomy from the dependencies of art, eschewing support from established galleries or art spaces. Instead the group concentrates upon building relationships between environmentalists, artists and employees of the core financial and carbon-extracting institutions which, at the same time, are the objects of their research and criticism. Since art has taken a relational turn, Platform’s dialogic practice has been somewhat vindicated and is gaining the interest of institutions with a commitment to engaging with ‘public issues’ outside the institutional safety zone.4 The group has often employed organised walks, ‘walking as a research tool, as a ritual, as performance, as intervention, as a political tool’.5 Here, in the Square Mile that demarcated the original Roman settlement of Londinium, Platform taps the rich network of influence and accumulation they call the ‘carbon web’ – ‘the web of institutions that extract oil and gas from the ground’.

Walking, I am accompanied by three voices or groups of voices. The protagonist, a disillusioned City worker, drifts, trying to throw off the pressure and hypocrisy of the city in an anguished monologue. The guide, a softly spoken, reassuring female voice, tells me when to cross, to ‘be careful’, ‘look left and right at the lights’, as well as offering information about BP, the financial groups and investors who support it (Morely, Deutsche Bank, Royal Bank of Scotland). The third voice is a chorus which echoes the protagonist’s monologue and riffs eccentrically on it, singing ‘They stole her nipples’, ‘look up, look up to the sky’, and, in the Royal Exchange, chants: ‘More, more and more, give us more money, give us more and more ... ’.

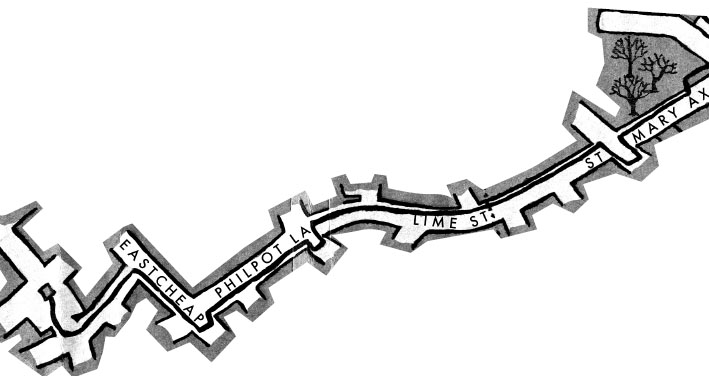

The carefully guided walk sometimes becomes a gallop as I realise I have taken a wrong turn or when the voices urge me to speed up. As I am led under and through the City’s architectural machines of accumulation, the opera emphasises its status as a principal node processing the world’s financial flows. Later, I am spun around Bank station and the Swiss Re tower as the chorus and music builds to a crescendo prefiguring a portentous end to the narrative and the walk.

The accompanying music first appears to me as corporate muzak, like the sound of distilled comfort and class played as one waits for the bank’s outsourced operatives to process your phone call. Later, the strings dramatise my rush around the city while street noise blends in as I lurch across streams of commuters and traffic. Once I accept that my route is programmed, I find myself caught up in what feels like the soundtrack to a live video game, gleefully aware that no-one else is conscious of my directed path.

And While London Burns is really an ‘experience’ – in the sense that a trip to Disneyland is. The walk deploys four dramatic elements: the narrative of personal crisis; the music; the information about the Earth’s decline under capitalism; and the sounds and sights of the City itself. As the slew of information about the Earth’s rising temperature builds to a picture of crisis, the protagonist becomes more erratic – we supposedly take on the burden of his self-realisation as our own. But then our ‘own’ crisis over climate change’s destructive potential is experienced as adventure.

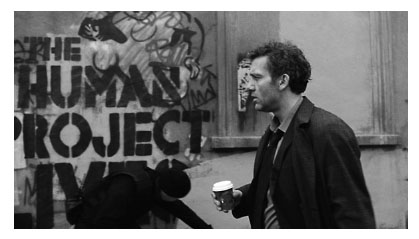

And While London Burns shares this array of simple mechanisms for dramatising the present really impending apocalypse with two recent films, Apocalypto and Children of Men. The latter plays out anarchist fantasies of a biopolitical neofascist state in the UK, presenting us with:

Image: still from Children of Men

a world one generation from now that has fallen into anarchy on the heels of an infertility defect in the population ... Set against a backdrop of London torn apart by violence and warring nationalistic sects, Children of Men follows disillusioned bureaucrat Theo (Clive Owen) as he becomes an unlikely champion of Earth’s survival. 6

Mel Gibson’s Apocalypto draws a clumsy comparison between the internal breakdown of Mayan civilisation prior to Cortez’s conquest of their lands and the demise of the US as a global hegemon:

Throughout history, precursors to the fall of a civilisation have always been the same .... It was important for me to make that parallel because you see these cycles repeating themselves over and over again. People think that modern man is so enlightened but we’re susceptible to the same forces – and we are also capable of the same heroism and transcendence.7

These films, like with And While London Burns, indulge a reactionary millenarianism apparently appropriate to our times characterised by anxiety over reproduction, environmental devastation, migration and wars over resources. Each locates a subjective response to ‘objective conditions’ in a male subject, and we see an awakening to the real conditions of the societies in which they live.

For And While London Burns’ authors one gets the feeling that it is something of a stretch of the imagination to place themselves in this character’s shoes, that some under estimation of the ignorant and complacent ‘suit’ is operating. The dynamic between the identification of the listener with this disaffected conservative and the more ‘radical imagination’ celebrated through historical references was, for me, unconvincing.

I struggle with the opera’s construction of experience (the listener’s as well as the conditions they ‘objectively’ face) as consensus reality without challenge. It seems that after so long working at the margins of artistic practice, Platform have finally conceded to the monoform. There is no transcendental subject, no lone saviour of civilisation. Although And While London Burns’ authors are the first to admit that they are self-consciously playing with clichés to dramatic effect, this walk is the very opposite of psychogeographic practice.8 The work engenders the opposite of an active, critical subjectivity.

If there is a dialectic to be found in And While London Burns it is that of flight versus contestation. The audio guide points to the irony of the City as both a centre of research into the causes and effects of climate change (in particular Swiss Re, whose reinsurance business is predicated upon the mediation of threats to profitability) and the self-satisfied ignorance of continued irresponsible plunder. As the opera’s story unravels we are informed that the protagonist’s partner, Lucy, has left to live ‘off-grid’. This response to the threat of environmental devastation is the conceptual equivalent of self-organising nuclear bunker drills at the height of the cold war – a duck and cover strategy, internalising the nuclear state’s imperative that we be afraid, that we submit to pointless rituals in the face of death. At the opposite pole, the rich shoring up their wealth and access to unadulterated leisure and consumption in Dubai are playing a similar end-game with equally futile consequences. As if, in the context of a global emergency, anyone will be safe in either a low impact woodland home with its own energy supply or in a glass tower surrounded by the best defenses petro-dollars can buy. Both visions indulge in the fantasy that in the globalised world there is some escape or autonomy, a form of denial which hopes to obscure all ties between that secure haven and the reality of ongoing surplus value extraction from a landless, illegalised, starving (sub-) humanity.

And While London Burns puts this contemporary meme of millennial conservatism to work in a locale that is synonymous with unsustainable economics, personal debt and risk-taking. The work chooses to reinforce the personalisation and internalisation of a crisis for which capitalism itself should be paying the costs. Its dramatisation of the Earth’s climactic instability hinges on a predicted four degree rise in temperature that we are now almost certain to reach according to the IPCC’s recent report. The facts relayed during the course of this walk tend to confirm these projections. I am not in a position to challenge these facts. Without even trying to challenge these facts, it is still possible to object to the terms in which the urgency of change is being framed. The injunction of climate change is literally ‘change’; through crisis, capital is reorganising itself and this has immediate social impacts. What is being proposed is a series of small adjustments for capital and many dramatic shocks for us. There appears to be very little going on in terms of large projects to actually reverse this situation, instead there is a confluence of self-righteous self-flagellation at a consumer level and government programmes to bully workers, small to medium-sized businesses and new home owners.

Platform have a background of deeper engagement with these issues and access to research that should allow them to analyse the joined up system of capitalist ‘wealth creation’ and its affect on the social environment. However, as the UK and other governments worldwide absorb green and environmental discourse and re-spin it as command – to eat less, work more, pay extra for energy and waste – some engagement with this instrumentalisation of ecological threat would be useful, rather than continuing to pursue an alarmist politics fuelling the fires of eco-fascism in becoming.

From apocalyptic predictions of dramatic climate change down to fashion tips for the greening of lifestyles, we experience exactly the same ‘terrorism of conformity that underlies all the publicity of modern capitalism’.9 The trouble with this work and almost all public discussion of climate, is that rather than critically evaluating the role of this ecological threat as part of the ongoing deterioration of living standards dictated by capital in most of the world, there is a tendency to exaggerate the threat, to rationalise it as a natural fact, and thus approve and provide training for the modification of behavior urged by capitalism.

Footnotes

1 Available for download at: http://www.andwhilelondonburns.com/download/

2 Anna Minton, ‘Down to a Fine Art’, The Guardian, 10 January

3 Platform website, http://www.platformlondon.org/aboutplatform.asp

4 Anna Minton, op. cit.. This celebratory piece highlights a new movement of artists fusing post-conceptual art and environmental art under the aegis of the Royal Society of Arts whose director, Matthew Taylor, was formerly head of the Prime Minister’s policy unit. It would seem that relational aesthetics is rapidly emerging as the idiom by which artists speak to policy makers on behalf of the public.

5 Platform website, op. cit..

6 Children of Men website, http://www.childrenofmen.net

7 Mel Gibson on Apocalypto from the film website, http://apocalypto.movies.go.com

8 As one definition would have it: ‘The theory of the combined use of arts and techniques for the integral construction of a milieu in dynamic relation with experiments in behavior’. Situationist International, ‘Preliminary Problems in Constructing a Situation’ in Ken Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, Bureau of Public Secrets, http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/1.situations.htm

9 ‘Geopolitics of Hibernation’, Situationist International #7, April 1962, http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/7.hibernation.htm

Biog

Anthony Iles <anthony AT metamute.org> is assistant editor of Mute