Under the Beach, the Barbed Wire

The 'race riots' in Cronulla at the end of last year made it clear that all is not well in Australia's multicultural paradise. Here, Angela Mitropoulos examines the racism, mechanisms of border control and changing conditions of work underneath the beach utopia.

If for a certain imaginary, the beach has often evoked a realm of authenticity hidden under the concrete strata of urban development, capitalist spectacle and exploitation, the relentlessly iconised Australian beach has, in addition, been put to use as proof of egalitarian sentiment and vast democratic horizons. Here, the generic vista of the Western frontier is shorn of its embarrassing wars over land, the guns and forts lined up against the natives, and redrawn as pre-economic, pre-political idyll. Never quite acknowledged as urban but, even so, presented as more urbane and civilised than either rural, uncultivated or desert lands, the space of the beach is assumed to have shaken off the dissensions of politics and economics much as the figurative beachgoer is presumed to effortlessly shed clothing. Like Rousseau’s state of nature, the mystical space-time of the beach operates as both a denial of the nation-state – the presupposition of the contrat social in its legal, political and not least, economic senses – and its naturalisation. And no more pronounced are these projections than in post-colonial spaces such as Australia, where persistent anxieties about unruly savages mingle with dreams of being closer to nature.

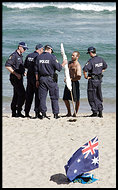

Popcultists have long campaigned for ‘the beach’ to be recognised as Australia’s eminent utopia. Some five years ago, Craig McGregor argued that the beach represents ‘our yearning for a world different from the concrete pavement universe that most of us inhabit for most of our lives. The beach today represents escape, freedom, self-fulfilment, the Right Path. It represents the way our lives should be.’ Similarly, John Fiske contended that the beach ‘is the place where we go on holidays (Holy Days), a place and time that is neither home nor work, outside the profane normality.’ It is perhaps not surprising that such homilies have become more pious just as coastal areas have become more developed, increasingly the scene of bloated property values, mortgage anxieties and a burgeoning tourist industry run mostly on precarious labour. Indeed, these hymns to ‘the beach’ are a crucial affective support in this political economy and these industries. And they leverage affection all the more fiercely when deployed as eulogies or calls to restoration. Therefore, it is in part because beachside suburbs do not provide for an indifferent repose – longed for as both fortress and refuge against difference – that they have become the scenes of overt violence, riot police and emergency ‘lockdown’ laws that seek to restore, by force, the order on which seaside utopics were assembled.

The enchantment of ‘the beach’ began in Australia in the late 1940s – which is to say, in the immediate post-WWII period and at the ideological high point of Fordism and the Keynsian settlement. That post-war accord between unions and employers took shape as a nationalist compact between descendants of the English upper classes and working class Irish. Persuaded by clerical anti-communism, promises of property and class mobility – in the form of the post-war housing ownership boom and university admissions – the latter were seduced into forgetting their genealogy as convicts deported from Britain under policies justified by their depiction as a separate ‘race’. This particular racialisation was set aside with the post-WWII Anglo-Celtic compact, which is the precise meaning of the figure of the Aussie and its egalitarian ethos – which is also an ethnos – of the ‘fair go’. Frozen in that dehistoricised and dreamlike zone after colonisation had been accomplished and before the collapse of the ‘White Australia’ policy in the early 1970s, the ostensible peace and contracted civility of the emblematic beachside has always depended on violence and separation, borders and fencelines, property and expropriation. In the final month of 2005 in Sydney, it was these contingencies that would be laid bare and, with recourse to emergency laws, reasserted as necessary for the restoration of what was deemed natural. It is not clear what the immediate inducement was. Lifeguards were assaulted, it is said, because they made racist slurs while attempting to stop people playing football (soccer) on Cronulla beach and, in the ensuing fight, came off second best. Cricket and Australian Rules (i.e., Celtic) football are commonplace on beaches and elsewhere – soccer, on the other hand, is regarded as the ‘wog’ game. Moreover, lifeguards are drawn from local residents, and their role is just as much concerned with beach safety as it is with enforcing the bonds between property and propriety. Yet, their authority on this occasion, derived as it is from a customary consensus over their iconic status, faltered. And so, this apocryphal confrontation over land use and the perceived failure of Aussie supremacy would converge with earlier tales in Sydney of ‘organised ethnic gangs’ rapes of Australian women’ and fears of miscegenation (in which women’s bodies are considered above all as racial property) to produce what, elsewhere, would be called a lynch mob.

As is more or less well known, around five thousand people gathered in Cronulla on December to ‘Take Our Beaches Back’ or, as it was put less obliquely in other circulating leaflets and SMS, ‘bash wogs and lebs’. Slogans such as ‘ethnic cleansing’ and ‘Aussies fighting back’ were prominent enough, on placards, posters and scrawled on skin, given force with punch and kick. Draped in Australian flags, singing Waltzing Matilda, large parts of the crowd rampaged around the suburb beating anyone they assumed to be a ‘wog’ or a ‘Leb’, including one woman whose parents migrated from Greece and a Jewish man. Such is the populist version of racial profiling – officiated more recently by the phrase ‘of Middle Eastern appearance’ – that has become standard in Sydney and at a time of a global biowar. It might be noted here that the women who were raped in the most prominent of recent cases in Sydney would not so easily have ‘passed’ as Australian in Cronulla that day, and yet their attackers would not have been given such unprecedented sentences if they had not been identified in court and the media as a ‘Lebanese gang’ targeting ‘Australian women’. Indeed, given that migration officials have deported or interned over a hundred people whom they incorrectly assessed to be ‘illegal non-citizens’ – such as Vivian Solon, a permanent resident deported to a hospice in the Philippines from her hospital bed after being hit by a car – suggests that this moment in Cronulla was, despite all the denials, continuous with the normative inclination of public policy and the racialising demeanour of the rights-bestowing, and rights-denying, state.

Since the events at Cronulla, there have been numerous accounts from the commentariat whose affective range is distinctly more elitist than anti-racist, demonstrating far more shock at the appearance of an unruly mob than the pogrom it enacted. But contrary to that perspective, which can only elicit demands for the restoration of law and order, the vulgar calls to reclaim ownership were merely the coarse, volunteerist expression of, most notably, the Prime Minister’s civic declarations of sovereignty (‘We will decide who comes here and the circumstances under which they come’), the more than decade-long policy of the internment of undocumented migrants by successive governments and, more recently, a war that is legitimated on racist grounds. As border policing became central to the conduct of elections and government policy throughout this period, the border was bound to proliferate across social relations and spaces, and in circumstances both casual and administered. This is why the worst of the attacks occurred in the train station. That train takes people from Sydney’s Central railway station to the nearest beach and, given the composition of Sydney as a whole, this includes people from the suburb of Lakemba, which has a high proportion of migrants from the Middle East. Cronulla, for its part, is notable for being the most Anglo-Celtic of suburbs in Australia. The Prime Minister once described the area as ‘a part of Sydney which has always represented to me what middle Australia is all about.’ Responding to the events at Cronulla, he would quickly deny that it was racism at work, adding: ‘I do not believe Australians are racist,’ and going on to propose that those who did believe such a thing lacked a cheerful disposition.

Over the subsequent three nights, there were retaliations. Hundreds of cars were smashed, people beaten and shops destroyed, as Cronulla and surrounding beachside suburbs were made unsafe for those whose belonging there had never before been threatened. One of the calls to retaliate declared:

Our parents came to this country and worked hard for their families. We helped build this country and now these racists want us out. [...] Time to show these people stuck in the 1950’s that times have changed. WE are the new Australia. They are just the white thieves who took land from the Aboriginals and their time is up. In the midst of this, the NSW Police Commissioner remarked that the Cronulla rally to ‘Take Our Beaches Back’ was a ‘legitimate protest’. It was, according to him, born of a ‘frustration’ with the failure of the police and the state to do their job, which is to say, to ensure the Australian border remained secure within Sydney. The Prime Minister insisted that the problem of ‘ethnic gangs’ – which he unequivocally denied those at Cronulla might be regarded as – should be left to ‘policy’, ie, the state. On the third day of rioting, the NSW Premier announced emergency laws to give police, among other measures, the power to ‘lockdown’ those beachside suburbs under threat. This was, he declared, a ‘war’ and the state would ‘not be found wanting in the use of force’. And so the task of the Cronulla pogrom was more smoothly accomplished by the police acting as border guards, refusing entry to the beaches to those who could not prove that they belonged there. The ‘lockdown’ laws, in summary, allow the state to remove entire suburbs from the ostensibly normal functioning of the law for periods of 48 hours. Among other things, and within the designated ‘lockdown’ zone, the laws remove the presumption of bail for riot and affray, allow for the area to be cordoned off to prevent vehicles and people from entering it, empower police to stop and search people and vehicles without warrant or the standard criterion of suspicion, and to seize cars and mobile phones for up to a week.

In some respects, this could be viewed as a sequel to the so-called ‘anti-terror’ laws; recast here as an explicit attempt to reterritorialise the ‘moving mêlée’ – as one journalist described those engaged in the retaliatory riots. Yet, just as the failures of border controls have prompted recourse to measures both militaristic and ferocious they have also reanimated the search for ‘social solutions’. If the culture industry and its disciples remain enthralled by a depoliticising understanding of ‘the beach’, there is no shortage of more conventional disciplinary approaches that, for instance, have found renewed impetus in psycho-sociological clichés: deviancy, crisis of masculinity, youth alcohol abuse and, not least but most comically, ‘ethnic gangs’ who listen to rap music and use mobile phones. All of these constructs do not simply deny the existence of racism. They practically deploy racism through the assumption that the problem is a failure of integration. In other words, they reiterate the classical sociological preoccupation with social or, more accurately, national cohesion. Here, having assumed the nation-state as a natural entity – often by obliquely rendering it as ‘community’ or ‘society’ – it is the appearance of divisions that are not expedient for and normalised by the very assembly of national unity which are registered as a problem to be solved. That such a perspective has been echoed by much of the Left, in their calls for a renewal of multiculturalism as a response to recent events, should in no way surprise, given that much of the Left continues to aim for representing the nation and its people. And, as it implicitly denounces both pogrom and retaliations alike as the abetting or cause of ‘racial disharmony’, this is ironically where the Left discloses the affective pull of its overwhelmingly Australian identification – an identity which is assumed to bestow rights universally and without exceptions that are legitimated through racism.

What is, however, remarkable is the extent to which multiculturalism continues to be idealised as a way of managing the exercise of ‘difference-in-unity’ that the nation-state at certain moments requires without, presumably, having to resort to either violence or criminalisation. Which is to say, it was precisely alongside the much-touted apex of multiculturalism as official state policy in the early 1990s that the policy of automatic and extrajudicial internment of undocumented boat arrivals was introduced. In that moment, internment camp sat comfortably alongside tributes to Australia’s diverse cultural mosaic, just as the most recent regime of border controls around the world were ushered in along with the ‘globalisation’ of trade and finance. For if multiculturalism was initially tendered as a better form of governance at the time of lengthy wildcat strikes by migrant workers in the early 1970s, this is because it offered an improved means of assimilating certain differences while criminalising those that did not align with the imperatives of national labour market formation. This is what the paradigmatic post-Fordist border has sought to realise: the filtering of antagonism into competition, difference into niche markets, and the recapitulation of an ostensible consensus over the nation as household firm vying for position in the world market. And it is on these questions that the part of the Left which retains some commitment to notions of class struggle has been either silent or expressed its bewilderment. Coming just days after the introduction of the ‘Workchoices’ policy (which principally seeks to restrict, if not entirely abolish, any remaining non-individuated work contracts), the inclination here has been to understand recent events as a distraction, much like racism – and indeed sexism – are routinely theorised as the diversions of an apparently otherwise unified class consciousness.

Yet there is no experience of labour in capitalism that occurs outside a relation to the border. This association does not arise simply because migration controls create legally-sanctioned segmentations within and between labour markets that, in turn, condition or ‘socialise’ the labouring circumstances of both immigrant and citizen. Nor does it occur only because, for instance, it is possible to show that the recent tendencies toward temporary residence permits and that of so-called ‘flexibilisation’ were both responses by employers and governments to a similarly coincident and prior exodus from the Fordist factories and the ‘Third World’ in the 1970s. Nor is it solely due to the fact that jurisdictions, currencies and the hierarchical links between them are manifest in every pay packet – although this is so obvious and therefore naturalised that it often needs emphasising.

While all of these are crucial in illustrating the significance of the border to the labouring experience, they are not quite sufficient to explaining the force of that relation, its acquiring a necessary disposition. To put this another way: the particular – which is to say, capitalist – nexus between labour and border comes about because the asymmetrical wage contract only acquires the semblance of a contract through the delineation of the figure of the foreigner. Put simply, without the foreigner, the notion and practice of the social (or wage) contract – as a voluntary agreement between more or less symmetrical agents – falls apart. There are three aspects worth considering here, and certainly in more detail: the conversion of the chance encounter into naturalised ‘origin’, the transformation of imperatives into individual choice, and the punctuated temporality of the contract which normatively distinguishes wage labour from slavery.

Firstly, capitalism acquires a ‘law-like’ character through the establishment of borders, whether those of nation-states or, more generally, enclosures. For while Marx’s ‘discovery’ of the surplus labour that lies behind the formally equivalent wage contract is more or less well known, it is the border that permits the chance historical ‘encounter between the man with money and free labourers’ to ‘take hold’ – as Marx noted, and Althusser would emphasise in his later writings. Secondly, the contract functions as the conventional mark of capitalism’s distinction from feudalism, asserting that individuals have the power to organise their lives, against the pressures of inherited inequalities, if not strictly as a matter of will, then at the very least, as performativity. The contract is a theory of agency and self-possession. It formally asserts indeterminacy (or freedom) by explaining and rationalising the substance of any given contract as the result of a concordant symmetry. Consider here the Australian Government’s ‘Workchoices’ policy that aims to replace ‘collective’ wage rates and conditions in particular occupations with individual contracts – that is, it is an instrument which seeks to generalise the conditions of precariousness that have existed outside the perimeter of the post-WWII ‘settlement’ referred to earlier. Responding to charges that this amounted to the reintroduction of coercion, since refusing to sign an individual work contract would entail not having the means to live, the Prime Minister responded: ‘Everyone who wants a job will have one.’ For the Prime Minister, the existence of coercion does not refute the contractual nature of waged work; it merely obliges a reassertion of contract theory. Let us, then, consider Rousseau’s argument that the ‘social compact’ requires ‘unanimous consent’ – or, more specifically, that ‘no one, under any pretext whatsoever, can make any man a subject without his consent.’ While this is often read as a foundational democratic argument against slavery and involuntary submission, it is more accurately the democratic substitution of the figure of the ‘born-slave’ with that of the ‘foreigner-by-choice’. In this way, the existence of submission (or slavery) is redefined as the consequence of an individual’s choice to reside within borders in which they do not belong – and they do not belong because they do not agree to the contract. In the Social Contract, after positing the natural foundations of the nation state in voluntary agreement, Rousseau goes on to argue:

If then there are opponents when the social compact is made, their opposition does not invalidate the contract, but merely prevents them from being included in it. They are foreigners among citizens. When the state is instituted, residence constitutes consent; to dwell within its territory is to submit to the Sovereign. Just as Rousseau’s perfect circle of democratic despotism cannot do without the ‘foreigner’, there is no semblance of the wage, as wage contract, without the border. This is the contingency of a specifically democratic capitalism, relating as it does to a certain axiom of money as universal equivalent and seemingly competent measure of all things, while preserving all the ambiguities through which repression, inequality, slavery and, not least, surplus labour-time are explained and stabilised. Given that there is no way in which someone might profit at the expense of another through an agreement that is indeed symmetrical, as the wage contract is asserted to be, racism (and sexism, which is never far away) prepares us for, distributes and rationalises asymmetry. The contractarian braces the contingent world of capitalist exploitation by ascribing it to individual authorship. Where this risks destabilisation, either by dissent or in the undeniable presence of inequality where all are born equal, the figure of the foreigner is put into service in the guise of the unpatriotic, the unassimilable and those deemed to be, for reasons of biology or ‘culture’, incapable of signing a contract, of the very capacity of individual authorship. It is the latter that most clearly emphasises the bond between exploitation and racism, between the surplus as understood by political economy and the extrinsic (the foreign) as conceived by demography.

Thirdly, while the punctuated duration of the wage contract customarily distinguishes wage labour from slavery, the ‘normal working day’ was always demographically and geopolitically rationed. Cronulla did not simply represent ‘middle Australia’, but also the ‘normal working day’. Seen from outside this limited perspective, borders have long operated as a form of detainment, beyond which the conventional (and perhaps simply Fordist) delineation between the time of life and that of work is suspended. In this sense, the distribution of racism (and sexism) is also the distribution of a particular temporality. Yet, today, the ‘regular’ tempo of work more closely approximates the temporality of slavery (and, not least, of housework), in that no firm distinction operates between the time of working and not working or, better: in the sense that unpaid labour time is laid bare as the condition of capital and the linear time of progress comes to a standstill.  The question then is, as it always was perhaps, how unpaid labour (or exploitation) is distributed, as well as whether it is counted or not. The Cronulla pogrom was as much about space, belonging and property as it was about relative advantage: about who is counted and who is detained, who might be said to possess one’s labour such that they might contract for its sale and who might be said to be a slave. Here, one might note the ways in which certain migrants are held up at the border, airport and detention centre, no less than the ways in which the banlieues have existed as a de facto space of internment. In this time of detainment, it is not labour (as something that might be disassociated and ‘sold’ by one’s self) that is stolen, but whole lives. It is not surprising, then, that the moving mêlée emerged here, as both description of a response to the Cronulla pogrom as well as apparition of chaos. Neither discernible as individuals nor enumerated as collective, with an emphasis on motion that is as spatial as it is temporal (appearing as quickly as it disappears), the moving mêlée had a whirlwind temporality that provisionally cut through the time of detainment even while it failed to escape it.

The question then is, as it always was perhaps, how unpaid labour (or exploitation) is distributed, as well as whether it is counted or not. The Cronulla pogrom was as much about space, belonging and property as it was about relative advantage: about who is counted and who is detained, who might be said to possess one’s labour such that they might contract for its sale and who might be said to be a slave. Here, one might note the ways in which certain migrants are held up at the border, airport and detention centre, no less than the ways in which the banlieues have existed as a de facto space of internment. In this time of detainment, it is not labour (as something that might be disassociated and ‘sold’ by one’s self) that is stolen, but whole lives. It is not surprising, then, that the moving mêlée emerged here, as both description of a response to the Cronulla pogrom as well as apparition of chaos. Neither discernible as individuals nor enumerated as collective, with an emphasis on motion that is as spatial as it is temporal (appearing as quickly as it disappears), the moving mêlée had a whirlwind temporality that provisionally cut through the time of detainment even while it failed to escape it.

Not surprising, either, that the ‘lockdown’ came into being here, as a reconfiguration of the mechanisms of detainment. And, it did not take long for a ‘lockdown’ to be invoked a second time. On January 1st in the country town of Dubbo, after indigenous teenagers fought with police against their attempt to arrest suspected car thieves, the police (as with the lifeguards in Cronulla) came off second best, and a lockdown was subsequently put into effect. Nevertheless, given the aim of halting movement through a shifting definition of lawlessness and a mobile decree of emergency zones, it needs to be emphasised that the form of the ‘lockdown’ predates the monumental pretext of 9/11. In a more direct sense, the ‘lockdown’ echoes the (offshore) internment camps and the excision of territories from the ‘migration zone’ that have characterised post-1992 Australian migration policies – a model that has since been explored by UK and other European governments. Moreover, much like the state of emergency declared in France after the riots of the banlieues, the suspension of the putatively normal functioning of the law duplicates the colonial encounter in a metropolitan context. For these reasons, it would be a mistake to construe this resort to emergency laws, such as the ‘lockdown’, as a mark of the triumph of border policing or, more generally, as cause for pessimism. Such instances do not signal a decline in our fortunes so much as they suggest the potentiality of a world that has surmounted its division into ‘First’ and ‘Second’, openly struggling with and against all the senses in which ‘our’ fortunes are dependent upon the expropriation of ‘others’.

Angela Mitropoulos has been involved in xborder, and written on borders, class composition and migration, including ‘Precari-Us?’ (Mute) and, forthcoming, ‘Cutting Democracy’s Knot’ (co-authored with Brett Neilson, in CultureMachine), and ‘Migration, Recognition, Movement’ (Constituent Imagination, AK Press)